Piece of Heart: Concerning Violence

Posted on December 26 2014 by Alexis S. Anderson

Welcome to the second installment of Piece of Heart, where we look at “The Legend of Zelda” series through the eyes of a literary professor and examine how its literary elements enhance the gaming experience. This week’s lesson is titled “More than it’s Going to Hurt You: Concerning Violence” and in a game series where the main protagonist is a swordsman, you can bet there are plenty of violent instances available for analysis.

Welcome to the second installment of Piece of Heart, where we look at “The Legend of Zelda” series through the eyes of a literary professor and examine how its literary elements enhance the gaming experience. This week’s lesson is titled “More than it’s Going to Hurt You: Concerning Violence” and in a game series where the main protagonist is a swordsman, you can bet there are plenty of violent instances available for analysis.

Ever been told to stop playing video games because they’re just filled with “mindless violence”? Well, these analyses will help you prove the naysayers wrong.

Violence is a multifaceted literary weapon, it has almost endless implications because of its almost endless varieties of execution. Violence in literature can be symbolic or thematic, a tool for plot advancement, or make a cultural or social statement; it can be used to show the fragility of life or the uncaring nature of the universe. Generally speaking though, there are two types of violence. Specific injuries like character-on-character violence, and narrative violence inflicted by an outside force where there is no real guilty party.

In terms of “specific injury,” the best examples are the different ways in which Ganondorf is defeated throughout the series. It varies slightly by game; a stab straight through the top of his skull, a finishing blow to the heart, multiple slashes to the face before a final jab, and so on. The brutality and form of each kill tends to reflect the tone of its game.

There’s no doubt that the direct plunge of the Master Sword into Ganon’s skull in “Wind Waker” is one of the most jarring finishes, which is ironic because of the adorable cartoony visuals of that game. It is fitting though, a very definitive way to kill Ganon in a game where even the flooding of Hyrule couldn’t. He even turned to stone afterward, it was a perfect end because it solidified the loss of old Hyrule and freed the emerging civilization to grow on its own.

The finishing blow to the heart hails from “Twilight Princess”, and it perfectly compliments the emotional nature of the game. The kids from Link’s home village had been kidnapped, his friend Colin nearly killed, his childhood friend Ilia given amnesia, his Princess’ life sacrificed, and his traveling companion presumably killed only minutes before this deadly confrontation. After all of this heartache, a thrust of the master sword straight into Ganondorf’s heart was well deserved. It was the culmination of Link’s griefs, as well as a merging of light and dark in that the blow occurred just after Midna’s defeat and so served as retribution for her.

In the case of “narrative violence” two situations stick out in my mind; Link’s mother in “Ocarina of Time” dying after escaping Hyrule and bringing infant Link to Kokiri, and the storm in “Skyward Sword” that sent Zelda down to the Surface. The main purpose of narrative violence is to provide plot advancement and thematic development; this is achieved in both of these instances by the revelation of a greater destiny for the involved character.

According to the Deku Sprout, Link’s mother escaped the fires of a civil war waging in Hyrule by fleeing to the Lost Woods with her child. She was gravely injured so she entrusted her child to the Great Deku Tree before dying. The war and Link’s mother’s death are the reasons for Link being raised Kokiri. If he hadn’t grown up in Kokiri Village it can be argued that the Great Deku Tree wouldn’t have called upon him nor assigned Navi to him, therefore barring Link from realizing his fate as the incarnation of the Hero of Hyrule. It’s also important that a civil war pushed Link from Hyrule, as the war refugee later became the war hero.

Similarly, Zelda wouldn’t have realized her lot as the incarnation of the Goddess Hylia had she not been sent plummeting to the surface in Skyward Sword. It’s later found out that Ghirahim caused the twister that knocked her out of the sky, but it was still an indirect attack especially because she didn’t land directly into his hands and was rather intercepted by Impa. It is Impa who educates her on her role as the Goddess, and the plot of the rest of the game is then set into motion as Link chases Zelda and Impa on their path to purify Zelda’s body at the Goddess statues.

Similarly, Zelda wouldn’t have realized her lot as the incarnation of the Goddess Hylia had she not been sent plummeting to the surface in Skyward Sword. It’s later found out that Ghirahim caused the twister that knocked her out of the sky, but it was still an indirect attack especially because she didn’t land directly into his hands and was rather intercepted by Impa. It is Impa who educates her on her role as the Goddess, and the plot of the rest of the game is then set into motion as Link chases Zelda and Impa on their path to purify Zelda’s body at the Goddess statues.

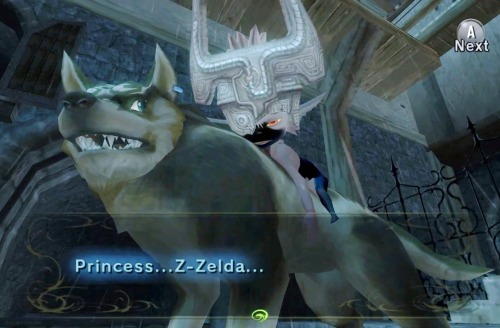

Moving on, the most emotional moment in “Twilight Princess” for me occurs when Zant drains Midna of all of her power and takes the fused shadows, then Zelda sacrifices her light to save Midna. Zant’s violent act toward Midna is clearly committed due to a need for power and to please his master Ganondorf, but we’ll cover power struggles later. What I want to focus on here is Zelda’s sacrifice.

It was practically suicide, which is the most affecting form of violence, and suicide as a literary tool typically identifies an inescapable horror and the destruction of self-determination. The depth of this scene is incredible because of this; Zelda had been imprisoned in her own castle, her kingdom taken over by darkness, and her only hope lay dying at her feet. There was nothing left for her to do but sacrifice herself so that her hero would have just a chance to emerge victorious. Midna had given Zelda grief earlier in the game for having allowed the darkness to envelope her kingdom rather than give her life fighting, so this sacrifice showed just how grave the situation became while serving as character and relationship development.

The theme of life being a fragile thing is well represented through Zelda’s “suicide” in “Twilight Princess”, but I feel that “Majora’s Mask” as a whole does a better job of expressing it. The moon is falling, good luck finding something more discouraging than that. The people of Termina didn’t know that they had a hero with a magical Ocarina crusading to save them, so it must have seemed to them as though the universe didn’t care a bit about their lives or town. They were utterly helpless, they could only abandon ship or stay to die in a violent planetary collision.

Social statements are tricky here, because they can either reference the society within the game, or society in the real world. The power complexes of the enemies across the franchise can be seen as reflective of the world we live in, and some reflect the in-game environment.

Ganondorf is King of the Gerudos by birthright, but it was never enough for him, he needed to rule the world. There’s always a problem with being given power just by birth, the rulers are typically hungry to establish themselves or just lackadaisical. Ganondorf was clearly the former, so the statement was one condemning inherent wealth and power. Because when not raised correctly the wealthy get a sense of entitlement and insensitivity to the needs of others, which was cause for his lack of remorse in conquering Hyrule.

On the contrary, Zant and Vaati act like spoiled confident brats when in reality they’re scared and confused people with inferiority complexes. The both of them lived under higher powers, so they felt oppressed despite being in fairly liberal environments. Both endeavored to gain unlimited power over vast areas of land, being that they were both young and naive they let their heads run away with the idea of power without thinking about it. This is why Vaati turned his master Ezlo into a cap, and Zant nearly killed his own Princess. In this case, the social statement is, with age comes wisdom.

On the contrary, Zant and Vaati act like spoiled confident brats when in reality they’re scared and confused people with inferiority complexes. The both of them lived under higher powers, so they felt oppressed despite being in fairly liberal environments. Both endeavored to gain unlimited power over vast areas of land, being that they were both young and naive they let their heads run away with the idea of power without thinking about it. This is why Vaati turned his master Ezlo into a cap, and Zant nearly killed his own Princess. In this case, the social statement is, with age comes wisdom.

Violent events in Zelda games serve as plot advancement mechanisms, add character development, make social statements, and add emotional depth. It’s impossible to cover every instance of meaningful violence in “The Legend of Zelda”, but I do hope these ideas will change some views on the violence present in the series.

Keep in mind, you can apply these lessons to literature, and thank you for reading! What did you think of this week’s lesson? Think you’ll try to look for the deeper meanings behind violence in Zelda from now on? Express your thoughts in the comments and feel free to add your own analyses of violence there as well!

Alexis S. Anderson is a Senior Editor at Zelda Dungeon who joined the writing team in November, 2014. She has a JD from the UCLA School of Law and is pursuing a career in Entertainment and Intellectual Property Law. She grew up in the New Jersey suburbs with her parents, twin brother, and family shih-tzu.