On Introductions

Posted on October 19 2012 by Hanyou

A Link to the Past arguably had the best opening sequence not just of any Zelda game, but of any video game. It introduces the player to the controls, the lore, the world, and the level design, and does so seamlessly while pushing Link forward through a rapidly-progressing story. Several pivotal things happen in succession, but they all make sense and set the tone for what’s to come.

A Link to the Past arguably had the best opening sequence not just of any Zelda game, but of any video game. It introduces the player to the controls, the lore, the world, and the level design, and does so seamlessly while pushing Link forward through a rapidly-progressing story. Several pivotal things happen in succession, but they all make sense and set the tone for what’s to come.

It’s the fastest-moving section of the game, and not only did it do a good job of setting things up, but it was a precursor to modern action games which start in medias res. Like Star Wars, it thrust its main character into the middle of a story that was much larger than he was — but it did so artfully.

It was the first Zelda game with a real introduction, and it started things off with a bang. Subsequent Zelda games would have wildly different beginnings, from the mostly docile Link’s Awakening to the bizarre Majora’s Mask to the (sometimes painstakingly slow) Skyward Sword, but none would ever reach for the frantic, quick, perfect pacing of A Link to the Past. No Zelda game since lacked a lengthy introduction sequence. The formula was in place, but there was plenty of room for variety within that formula.

What makes A Link to the Past’s opening so iconic is in large part its progression, pacing, and variety. At first, it provides backstory in a conventional literary format, with scrolling text and a slide show. Immediately, we’re dropped into the setting of Link in his home — but unlike subsequent games, there is absolutely no opportunity for him to rest. He’s immediately contacted by Zelda, his uncle immediately leaves, and not a word is wasted between the characters.

This vital beginning part of the introduction is the first thing a player sees in a game, and in subsequent entries the developers almost always opted to keep things calm. Ocarina of Time might be the quintessential example, and it’s handled well there. The beginning is ominous and properly sets the stage, and once again not a word is wasted between characters. We’re given a preview of events to come and the Deku Tree explains the stakes. This segment ends when Link leaves his house and enters Kokiri forest, a comfortable environment full of optional tutorials. The Wind Waker sets up its premise with text and a slide show which are less ominous and more grandiose, capitalizing on the mystery of Hyrule’s past. Majora’s Mask, like A Link to the Past, doesn’t feel safe at the beginning; the player is pushed forward through an uncomfortable series of events in which he or she actively participates before plunging into a real tutorial section.

Some games either seem to lack this type of prologue entirely, or else it is hard to draw a distinct line between the prologue and the introduction proper. Twilight Princess simply drops us into Ordon with no real stakes set up. Skyward Sword’s prologue is on its title screen, so you could play the entire game without once seeing it. This is the same approach taken by The Legend of Zelda, but as we will see later in this article, it has different results. This setup is important if you care about the world, but the choice to leave it out is an artistic choice and it is entirely nonessential to the gamer’s experience. It is cinematic, which is never a bad thing unless it is taken too far.

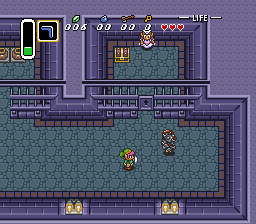

The tutorial section follows the prologue. Once again, A Link to the Past provides some insight into how this is properly accomplished. By interacting with the overworld and the first dungeon, the player is forced along a linear path, but the experience feels very organic. We’re encouraged to respond directly to the game’s environments, and it helps that Nintendo crafted them to be as interesting as possible. The castle proper is an intimidating maze of twisting corridors filled with dangerous enemies. If you act carelessly, you will die. It is also so varied that it test’s the gamer’s skill level in several different situations, with different types of puzzles and action brought to the fore. There are choices to make in how you approach different situations, with stealth remaining optional but combat forced on the player at some key points. It is impossible to leave the first dungeon without at least rudimentary knowledge of how the game operates. You’ve learned by rote — by repeating things over and over — but thanks to good design, it was fun and rarely repetitive. Furthermore, the story was always present, capitalizing on the initial setup. By the time Link finally arrives in the Sanctuary, the game has explained itself sufficiently.

The point is, while this is brilliant as a tutorial, it’s also fantastic as part of the game. After my first playthrough, I never once felt like I was playing through a tutorial, even as the game was functionally re-explaining itself to me. It’s artfully crafted and completely tasteful. In this age of lengthy, obvious tutorial sections for games, it’s a strong example of how to avoid the obvious approach while still delivering important lessons about controls and gameplay.

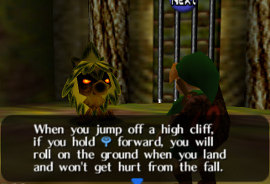

Ocarina of Time is equally good, but in different ways. The tutorial starts right as you leave your house, and divides itself between overworld interaction — things like collecting rupees, talking to people, and simply navigating the intimidating locations — and dungeon-crawling. It contains more obvious explanations than A Link to the Past, like signs and NPCs that tell you what to press in what situations, but it still plunges you right into the game. Most of the literal tutorials are purely optional, so you never have to “relearn” something you have no interest in, but almost everyone and everything in Kokiri Forest has some role to play in explaining the game to you.

Ocarina of Time is equally good, but in different ways. The tutorial starts right as you leave your house, and divides itself between overworld interaction — things like collecting rupees, talking to people, and simply navigating the intimidating locations — and dungeon-crawling. It contains more obvious explanations than A Link to the Past, like signs and NPCs that tell you what to press in what situations, but it still plunges you right into the game. Most of the literal tutorials are purely optional, so you never have to “relearn” something you have no interest in, but almost everyone and everything in Kokiri Forest has some role to play in explaining the game to you.

Once you finally have a sword and shield, you make it to the Deku Tree. As with A Link to the Past, it is both the first dungeon and a tutorial dungeon. Unlike A Link to the Past, this dungeon is fully fleshed-out, with its own boss and a full set of dungeon items and puzzles. This works because of Navi, who points out the obvious to people who have already played the game, but helps new players along and fortunately isn’t too intrusive in either case. As a whole, the whole tutorial section is slower than A Link to the Past’s, but is just as artfully constructed.

The Wind Waker operates in a similar fashion, with much of Outset serving to introduce you to the mechanics. However, the tutorial portion is much longer, arguably lasting through the entire first dungeon, well into the meat of the game. This does make it more of a chore and less of an engaging experience than it could be, but like Ocarina of Time and A Link to the Past, a good portion of it is legitimate gameplay. Going over the nuances would take too long, but each section of the tutorial introduces different aspects of the gameplay. This does not make it unique, but its approach is particularly lengthy, perhaps the longest of any Zelda title.

Majora’s Mask is perhaps the most challenging, the most odd, and to some, may be the most rewarding. You’re left to figure things out for yourself by a certain deadline, and failure to meet that deadline results in the worst possible ending. This is true of the game as a whole, but not having the ability to properly save your progress adds an additional element of fear to this portion of the game. As with A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time, it introduces you to the underlying mechanics.

Finally, Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword share similar approaches, and they are the weakest. A bit of hand-holding took place in The Wind Waker, but at least the mechanics weren’t explained painstaking detail by painstaking detail as you were ferried from one location to another. As with A Link to the Past, you learn by rote in all the tutorials, but that approach is taken quite literally by Skyward Sword and Twilight Princess, forcing the gamer to do meager tasks that gets the game off to a slow start. Some of these tasks can even be frustrating, like fishing with the Wiimote or parachuting right into the center of a circle, and they are nothing but busywork. Worse, the reward for completing these tasks isn’t proper gameplay, but more text. You’re led through the twisting corridors of unnecessarily slow-moving stories, and it takes a good amount of time before free navigation even feels like an option.

Finally, Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword share similar approaches, and they are the weakest. A bit of hand-holding took place in The Wind Waker, but at least the mechanics weren’t explained painstaking detail by painstaking detail as you were ferried from one location to another. As with A Link to the Past, you learn by rote in all the tutorials, but that approach is taken quite literally by Skyward Sword and Twilight Princess, forcing the gamer to do meager tasks that gets the game off to a slow start. Some of these tasks can even be frustrating, like fishing with the Wiimote or parachuting right into the center of a circle, and they are nothing but busywork. Worse, the reward for completing these tasks isn’t proper gameplay, but more text. You’re led through the twisting corridors of unnecessarily slow-moving stories, and it takes a good amount of time before free navigation even feels like an option.

The tutorial section of Zelda games has gotten increasingly tedious in recent years, which is especially confusing since A Link to the Past, Ocarina of Time, and Majora’s Mask executed it so skillfully. It’s gone from taking only a few minutes, to taking an hour, to taking much longer. The tasks have gone from intuitive, natural, and partly optional, to mandatory and obnoxious. While recent Zelda introductions serve to create atmosphere and set up the story, and in Skyward Sword’s case are successful on a first playthrough, they could stand to learn from previous tutorial sections.

Finally, the introduction usually has some sort of coda, or concluding event. In A Link to the Past, it’s clear when you arrive in the Sanctuary with Zelda and are informed of the stakes for the last time that you’re ready to be sent into the much larger world of Hyrule. Ocarina of Time is almost identical in its approach, with the Great Deku Tree giving Link a cinematic sendoff and dying, and Link saying farewell to Saria before entering the much more open Hyrule Field. Majora’s Mask sees Link bestowed with the Ocarina before a preliminary showdown with the Skull Kid.

In more recent games, it’s hard to identify a “coda” because it isn’t as clear quite where the tutorial ends and the game begins. In The Wind Waker, it’s probably around the time you get the game’s namesake and set sail from Dragon Roost. In Twilight Princess, it’s probably around the time you make it to the first dungeon, which isn’t a tutorial dungeon like its predecessors. In Skyward Sword, it probably hits around the time you get to the surface.

The introduction is one of the most important sections of any game, and it’s been particularly important to the Zelda franchise since A Link to the Past. It helps set a tone for what follows, explain the story, and most importantly, establish the gameplay mechanics. While each introduction has something to offer, it’s the more concise ones, or at least the ones that serve to plunge you right into the gameplay proper, that have more lasting charm.