Link’s Awakening and Character Development

Posted on July 29 2011 by Hanyou

The Legend of Zelda series has, for most of its lifespan, been viewed as a franchise with a quality story. Nowadays, we have rich lore to draw from, to formulate complex theories about multiple timelines and Hyrules, multiple versions of the main characters and side characters. But things weren’t always like that.

The Legend of Zelda series has, for most of its lifespan, been viewed as a franchise with a quality story. Nowadays, we have rich lore to draw from, to formulate complex theories about multiple timelines and Hyrules, multiple versions of the main characters and side characters. But things weren’t always like that.

The original Legend of Zelda was straightforward. The story was simply a quest from point A to point B, and the gamer was left to fill in the gaps. The vast landscape provided a sort of sandbox for the gamer to formulate their own stories, and the journey itself was decidedly epic. But it was missing history. Zelda II, of course, added the necessary history and lore, along with populating Hyrule. Faceless old men were replaced by people who had a variety of ages, and basic fetch quests became a part of the gameplay as characters would ask Link to seek out an item or provide him with new spells. A Link to the Past mastered presentation, adding depth to the world by changing its environment. Once again, however, character development remained mostly intact. The old men now had names, but the player rarely got to know them very well, and even Zelda herself, in spite of taking an active role in events early in the game, was far less involved in the proceedings than she could have been.

There was nothing wrong with this sort of approach; in the first three games, the world was the star. The Legend of Zelda had tackled breadth, imbuing Hyrule with a rich, large world. Zelda II tackled lore. A Link to the Past expanded on both while offering atmosphere. These are all essential components to the experience of a modern game, and arguably to a truly layered artistic experience. But something was still missing.

Enter Link’s Awakening.

It’s difficult to question whether the earlier games would have benefited from deeper character development like their peers had. But Link’s Awakening almost mandated it. In previous games, characters were objective markers. They might superficially provide some dialog to help the story along, and in A Link to the Past the developers clearly tried to imbue at least some of them with personalities of their own. But they lacked apparent self-awareness and any apparent function outside of Link’s quest to save Hyrule.

In Link’s Awakening, characters still represented checkpoints. They still existed to inform Link about changes in the world and give him items necessary for advancement. But their existence was much more than superficial, and in only the first few hours of the game, it became apparent that they had individual identities. Lives. Dimensions. They didn’t exist simply to help Link or make his quest more difficult; they existed of their own accord, with their own lives and desires, and the player, through Link, could have the privilege in taking part in those lives.

In Link’s Awakening, characters still represented checkpoints. They still existed to inform Link about changes in the world and give him items necessary for advancement. But their existence was much more than superficial, and in only the first few hours of the game, it became apparent that they had individual identities. Lives. Dimensions. They didn’t exist simply to help Link or make his quest more difficult; they existed of their own accord, with their own lives and desires, and the player, through Link, could have the privilege in taking part in those lives.

One fairly basic example is Mr. Write. His name also works as a description of his character; his hobby is writing letters to various people. During the game he maintains a long-distance relationship with Christine, a character from animal village, and Link acts as a courier between them.

This simplistic story shows only rudimentary depth, but that’s all it needs. Mr. Write’s subquest, and his interactions with Christine, are sufficiently engaging and funny. They even include an unexpected plot twist. Encounters like this are not the exception but the norm in Link’s Awakening, and even when they provide items necessary to the main story, characters’ personal development does not always have to do with that main story. The best stories in Link’s Awakening are the little ones, the character moments that add real depth to the world. Almost every hut houses a character who can both contribute something to Link’s quest and provide an amusing anecdote of their own. Players may not always remember which item they receive from which character, but they will remember the characters’ stories, and thus is achieved the last basic tenet of storytelling that Zelda was missing.

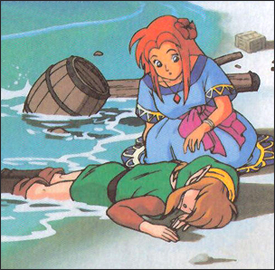

The most well-known characters, of course, are Marin and Tarin. Both are with Link from the outset, and they are integral to his progress throughout. Tarin gets into a ridiculous situation early in the game, and Marin always seems to have something to contribute. For various reasons, returning to Mabe Village, the first village Link encounters in the game, is refreshing. Koholint Island as a whole is volatile and dangerous, filled with difficult monsters who are always on the hunt. Mabe Village provides a restful pause from the action of the game, and in that respect, it’s a location that has serious implications for gameplay. But there’s more to it than that. Each of the characters in Mabe Village has an associated quest or minigame, and each of them looks distinctive. The village ceases to be simply a location–it’s a gathering place for major plot points, humorous anecdotes, and of course, memorable characters.

Marin is the most well-developed of these characters. An important part of the game has Marin follow Link around Koholint island. Several of the interactions between Link and Marin–which are captured on camera in the DX version of the game–are purely optional. The gamer is likely to stumble upon them only because Marin is a required “item” for the progression of the plot. Each of these interactions, however, has wonderful implications for characters in the game. Not only do Marin and Link interact with each other, and do so convincingly, they also interact with their world and other characters. Attempting to jump down the well or entering the Trendy Game house, for example, will lead to humorous moments. In addition, Link’s Awakening has come closer to actually developing a romance between two major characters than any Zelda game before or since. Link and Marin’s relationship is a gradual one, but there are several times when the game hints that they may be developing feelings for each other.

Marin is the most well-developed of these characters. An important part of the game has Marin follow Link around Koholint island. Several of the interactions between Link and Marin–which are captured on camera in the DX version of the game–are purely optional. The gamer is likely to stumble upon them only because Marin is a required “item” for the progression of the plot. Each of these interactions, however, has wonderful implications for characters in the game. Not only do Marin and Link interact with each other, and do so convincingly, they also interact with their world and other characters. Attempting to jump down the well or entering the Trendy Game house, for example, will lead to humorous moments. In addition, Link’s Awakening has come closer to actually developing a romance between two major characters than any Zelda game before or since. Link and Marin’s relationship is a gradual one, but there are several times when the game hints that they may be developing feelings for each other.

Thus, it is not just the side characters, but characters who are central to the plot who are developed in Link’s Awakening. Gameplay encourages the player to engage in character development, to learn more about Link and the other characters, but doesn’t always force it on the gamer. All of this is evidence both of good game design and good storytelling, and Link’s Awakening finally unified all the vital elements of a good plot. There were no faceless residents of Koholint Island. No longer were NPC’s nondescript, and no longer were they classified solely by how they responded to Link.

Ocarina of Time would develop this exponentially, but it would not improve on it. All the necessary groundwork was laid in an 8-bit, monochrome, oddball Zelda title with a strange sense of humor and a quest that didn’t take place in Hyrule. Link’s Awakening was the pivotal moment in storytelling for the Zelda franchise.