Zelda and the Silver Screen: Archplot and Miniplot

Posted on August 31 2012 by Legacy Staff

The idea of a film adaptation of The Legend of Zelda series has been tossed around numerous times throughout the years, though to date no official adaptation has been produced, and many fan-based adaptations have been met with mixed reactions. To many, the idea of a Zelda film is very foreign, as the core tenets of the Zelda series do not lend themselves well to the cinema upon first glance. Looking closer, however, there are a number of interesting parallels to screenwriting theory within the structure of various games in the series.

The idea of a film adaptation of The Legend of Zelda series has been tossed around numerous times throughout the years, though to date no official adaptation has been produced, and many fan-based adaptations have been met with mixed reactions. To many, the idea of a Zelda film is very foreign, as the core tenets of the Zelda series do not lend themselves well to the cinema upon first glance. Looking closer, however, there are a number of interesting parallels to screenwriting theory within the structure of various games in the series.

In film theory today, one of the most dominant methods of screenwriting is based upon the teachings of Robert McKee, a renowned lecturer and author known for his Story seminar about the structure not only of films, but of stories in general. In this article we are going to examine McKee’s plot triangle and discuss the ways that Zelda games match the different corners of the triangle, and how this makes it well suited (or in some cases ill-suited) to film adaptation.

The Plot Triangle

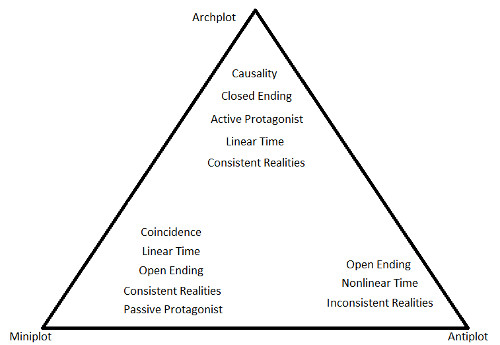

McKee’s plot triangle is an arrangement of three specific types of plots that is used to classify various stories. While in both his seminar and his book he goes in depth regarding the spaces in between the corners of the triangle, for the sake of simplicity we’re going to focus on the three corners, which represent the three pure forms of plot: archplot, miniplot, and antiplot.

At the top of the triangle, we have the archplot, or the “classical design”. This is by far the oldest and most persistent of the three plot variants (hence “arch”)—most examples of the Hero’s Journey will fall neatly into this category, and most strongly plot driven films will mirror this design. When you’re looking at the three-act plot structure common in modern media, you’re looking at the classical design. The archplot is the best fit for films that seek to tell a story on a large scale with high stakes. This is where Star Wars, The Avengers, The Godfather, and Inception fall—most of your summer blockbusters and well known classics will fall under this category. In the bottom left corner, we have the miniplot, which stresses minimalism of classical design. Note that the aspects of classical design are still going to be present—the Hero’s Journey, for instance, will still be intact—but in a minimal state, with aspects other than the plot taking center stage. Miniplots tend to be the most suitable structure for films that seek to explore smaller parts of a larger story. Though somewhat rarer in film than the archplot, miniplots can be seen in films such as Pulp Fiction and Inglourious Basterds. In the bottom right corner, however, we have antiplot—rather than reducing the aspects of classical design, it reverses them entirely. Antiplots tend to work best for films that seek to comment on story structure itself. These are very rare in film, and occur more often in the experimental, arthouse cinema genres—most notably, 8 1/2, Chungking Express, and—oddly enough—Wayne’s World, fall into this category.

These are very rudimentary descriptions of these types of plot—but don’t worry. We’re going to be talking about each kind of plot extensively when comparing it to various games in the series. For now, only a basic understanding of the relationship between these types of plot is needed. This week, we’ll be examining the most significant examples of archplot and miniplot in the series. Additionally, in the triangle above, you’ll notice a number of terms listed near the type of plot; these are all terms we’re going to discuss in greater depth in the next few sections.

While both a miniplot and an archplot would be perfectly suitable for the screen, a potential Zelda film would most certainly belong to the fantasy epic genre—a long tradition of films including, most significantly, The Lord of the Rings trilogy. One of the most critical aspects of films in this genre is their scale—they are all very large scale productions with stories that often involve the fate of the entire world in which it takes place. Such a large scale is something that a miniplot cannot provide as easily as an archplot; as such, for a Zelda film, an archplot would be far better suited for film adaptation than a miniplot. In discussing this idea further, we’re going to use Skyward Sword, the most significant example of an archplot in the franchise, and Ocarina of Time, the most significant example of a miniplot, as examples.

Plot: Causal vs. Coincident

The first thing to be considered when examining an archplot or a miniplot is the plot itself, but more specifically, the plot as distinct from the story. Rather than look at the details of what happens, we need to examine the way that the events unfold. In most every case, events unfold in one of two ways—in a causal way, or a coincident way.

The first thing to be considered when examining an archplot or a miniplot is the plot itself, but more specifically, the plot as distinct from the story. Rather than look at the details of what happens, we need to examine the way that the events unfold. In most every case, events unfold in one of two ways—in a causal way, or a coincident way.

The causal method, corresponding to the archplot, involves events that unfold as a direct result of the previous event. To use Star Wars as an example, the Imperial attack on the Rebel cruiser at the opening of the film leads to R2-D2 and C-3PO’s escape to Tatooine, which then leads to their purchase by Luke’s uncle, which leads to R2’s distress message of Princess Leia motivating Luke to seek out Obi-Wan Kenobi. The events unfold in direct sequence, each event influencing the next. In Skyward Sword, we see this very clearly, particularly in the early stages of the game. Once Link has descended to the surface, his direct goal is to find and rescue Princess Zelda, a mission which leads him to the Skyview Temple in the deep Faron Woods. Because he fails to find Zelda there and instead learns that she had moved on to a new spring in the Eldin Volcano region, he continues his quest in that region. Had he found Zelda at Skyview, however, his quest would have proceeded rather differently—perhaps he would have skipped over the initial Eldin quest entirely. The events of Eldin are a direct result of Link’s failure to reach Zelda at the Skyview spring—hence the causal nature of the game’s plot.

The coincident method, corresponding to the miniplot, involves events that unfold separately of each other and cross paths by coincidence. A film example would be Pulp Fiction—the story of the gold watch and Butch the boxer is entirely separate from the story of Vincent Vega and Jules Winfield. They only cross paths due to a mutual boss, Marcellus Wallace, and a coincidental appearance of Vincent in Butch’s story. Butch’s fight and his subsequent flight from Los Angeles is entirely unaffected by Vincent and Jules’ retrieval of the briefcase from Brett—the events unfold independently, and cross paths by coincidence. In Ocarina of Time, we see this slight disconnectedness with the segmented quests for the Spiritual Stones and the Sage Medallions. While Ganondorf’s interventions throughout Hyrule serve as unifying factors, the quests for each individual stone and medallion are ultimately separate, self-contained stories. Link’s actions on Death Mountain in Dodongo Cavern have no impact on Link’s subsequent actions in Zora’s Domain and Jabu-Jabu’s Belly, just as his actions in the Forest Temple have no impact on his actions in the Fire Temple. While the main quest naturally intersects these separate stories at certain points, such as the opening of the Door of Time and the final encounter in Ganon’s Tower, the existence of these independent, separate stories indicates that Ocarina of Time’s plot is one governed by coincidence rather than causality.

While it is by no means a universal rule that causal plots make for better films than coincident plots—after all, Pulp Fiction is praised almost as much as Star Wars in most film circles, if not more—in the cases of epic fantasy films, segmented plots can often descend into a feeling of aimlessness. After completing one of the many independent quests, there would be a low point during which Link would have to find his next course of action. A low point here and there is not an inherent weakness, but consistent low points throughout the film result in a segmented feel that can bore the audience. A causal plot, however, has the advantage of keeping the audience attached and driven by the same goal throughout. Because events unfold as a direct cause of the previous one, the plot unfolds more naturally without the awkward low points between segments. As a result, the structure of Skyward Sword would make for a better paced film than would the structure of Ocarina of Time.

Resolution: Closed vs. Open

The ending of a film is just as critical as the beginning—while the beginning of the film sets the tone for the rest of the film, the ending imparts the audience with a departing mood, and influences their feelings as they leave the theater. Most simply, there are two types of endings: a closed ending and an open ending.

The closed ending is associated with the archplot. As Robert McKee described it, a closed ending is one after which the audience can imagine no further action. This is not to say that the audience cannot imagine new stories taking place with the same characters in the same environment, but rather that all ends of the story being told are resolved, and that the audience cannot imagine the continuation of the conflict at the core of the story. A closed ending does not mean that sequels are ruled out. To use Skyward Sword as an example, while not only can we imagine events in Hyrule that take place after the end of the game but actually experience these events in later games in the chronology, the events of the game are definitively resolved. Demise is killed and Link and Zelda begin to colonize the surface. We can certainly imagine their actions during that endeavor, and perhaps even imagine new conflicts regarding the remaining surface creatures. But because the central conflict of the game is ultimately resolved, it is a closed ending.

The closed ending is associated with the archplot. As Robert McKee described it, a closed ending is one after which the audience can imagine no further action. This is not to say that the audience cannot imagine new stories taking place with the same characters in the same environment, but rather that all ends of the story being told are resolved, and that the audience cannot imagine the continuation of the conflict at the core of the story. A closed ending does not mean that sequels are ruled out. To use Skyward Sword as an example, while not only can we imagine events in Hyrule that take place after the end of the game but actually experience these events in later games in the chronology, the events of the game are definitively resolved. Demise is killed and Link and Zelda begin to colonize the surface. We can certainly imagine their actions during that endeavor, and perhaps even imagine new conflicts regarding the remaining surface creatures. But because the central conflict of the game is ultimately resolved, it is a closed ending.

The open ending, associated with the miniplot, marks an ending that leaves further action or emotional resolution to the imagination of the audience. Ocarina of Time’s ending is a perfect example—though much of the conflict of the game is resolved, because Ganon is sealed rather than killed, it is very easy to imagine further action taking place. What makes this further imagined action distinct from continued conflict in a closed ending is that it is an extension of the conflict within the game—Ganon breaking out of his seal and returning to conquer Hyrule is very much an extension of the main story of Ocarina of Time, whereas the appearance of a new enemy after Skyward Sword, while arguably related to Demise, is ultimately a new conflict rather than a continuation of the game’s resolved conflict. Additionally, there are further conflicts that are directly implied by the events that take place in Ocarina of Time, as well as missing emotional resolutions associated with them. When Link is returned to his past before the events of the game occur, there are many unanswered questions—do things happen the same way? What changes, and why is it different? Does Navi still come to Link? If not, how does Link handle the loss of his friend? What about the loss of all the people Link had forged friendships with over the course of the game? All of these lingering questions create an open ending that fails to provide total emotional resolution.

The closed ending is better suited for film adaptation because it allows for a self-contained experience that fully resolves itself emotionally. While many films opt for an open ending in the modern industry, in almost every case those films are intended as the first in a series of films that will follow up and provide additional exposition and resolution, with the end of the series often providing the full resolution necessary of a closed ending. While both Skyward Sword and Ocarina of Time are mostly self-contained stories, only Skyward Sword sufficiently wraps up its central conflict in a way that the audience will feel as if things have ended totally; Ocarina of Time’s open ending will leave them anticipating further action.

Protagonist: Active vs. Passive

Lastly, we must examine the ways in which Link, the protagonist of both games, acts. McKee’s theory of the protagonist is very extensive, so we’re going to discuss it in a very brief form. Firstly, protagonists are willful characters; they have great willpower and work unceasingly to accomplish their goals. Secondly, they all have a conscious desire and work to fulfill that desire. What varies from protagonist to protagonist is whether they are active or passive characters, a trait determined by the ways in which they attempt to fulfill their desire.

Lastly, we must examine the ways in which Link, the protagonist of both games, acts. McKee’s theory of the protagonist is very extensive, so we’re going to discuss it in a very brief form. Firstly, protagonists are willful characters; they have great willpower and work unceasingly to accomplish their goals. Secondly, they all have a conscious desire and work to fulfill that desire. What varies from protagonist to protagonist is whether they are active or passive characters, a trait determined by the ways in which they attempt to fulfill their desire.

The Link of Skyward Sword is very much an active protagonist—he has a clear, conscious desire that he actively works toward throughout the entire game. All of his actions are predicated on the desire to save Zelda and return her to Skyloft. There is no immediate threat pushing him forward; he chooses to leave the safety of Skyloft to travel to the world below and to save Zelda of his own accord. Additionally, Link takes a greater initiative in Skyward Sword than he does in other Zelda games, operating primarily alone, for his own reasons, with Fi’s assistance.

In other games, such as Ocarina of Time, Link is considerably less active, and instead trends toward a passive protagonist. Some may note that Link takes action just as much in Ocarina of Time, and while he certainly does take action, I ask: what is his conscious desire? What about Link suggests that he wants something that he is constantly working toward? It’s far less clear what exactly Link desires in Ocarina of Time, as the call to adventure is a very literal call from the Great Deku Tree rather than an event that Link reacts to. Unlike the Link of Skyward Sword, this Link does not take direct action on his own accord; instead, he (willingly) does the bidding of the Great Deku Tree, of Zelda, and of Rauru. Throughout the game there is little to suggest Link’s own desires. This is because Link is a passive protagonist, one who pursues desire inwardly while acting on the desires of others. Is Link’s desire to make everybody happy? Is it to save the world? We don’t really know, because Link plays these very close to his chest—he is passive regarding the pursuit of his desire. Note that this isn’t because this Link does not have desires—after all, every protagonist has desires—but that rather than actively pursuing them outwardly, he is passively pursuing them inwardly, and as such his desires are not as readily apparent to us as are the desires of an active protagonist.

It’s not very difficult to see why an active protagonist is far preferable to a passive one in the context of a film. When the events of the film are viewed through a specific character, that character needs to have the same drive and desire to reach the end that the audience does. If the character is not ostensibly driven or seems to only be doing the bidding of others, the audience will not identify with him very readily, and thus the film will lack the emotional heft of one that has an active protagonist who engages the audience’s interest. Skyward Sword’s Link, with his desire to save Zelda and be with her romantically, would resonate far stronger than the stoic and somewhat inaccessible Link of Ocarina of Time.

Conclusion

It’s rather clear that Skyward Sword, with its heavy archplot, would be better suited for film than would Ocarina of Time. The miniplot of Ocarina of Time is far better suited for video gaming, as it allows the character the opportunity to engage with the separate regions independently, rather than as part of a single, unbroken plot thread. It also affords the player the opportunity to project themselves into Link, as his lack of desires allows players to create their own desires and act on them accordingly.

The overall point is this: while Skyward Sword’s structure is better suited for film than is Ocarina of Time’s, the miniplot of the latter game is in no way lesser than the archplot of the former. They are different styles that aim to accomplish different things, and that diversity is one of the hallmarks of the Zelda series.

In my next article, we’ll discuss the third type of plot in McKee’s triangle, the antiplot, and how it relates to Majora’s Mask, as well as discuss the inherent difficulty of translating the strengths of a video game series, an interactive medium, to the screen.