The Divinity of Jabu-Jabu: Zelda’s Kami

Posted on May 18 2012 by Djinn

Ever since they first appeared in Ocarina of Time, there have been a lot of questions regarding the divinity of both Jabu-Jabu and the Deku Tree, though Jabu-Jabu especially. Many fans ask just how they qualify as deities. They are by no means gods as Western audiences understand. They live and die, they are tangible, physical, breathing beings living in Hyrule like any other mortal race. “Clearly,” the Western audience must be thinking, “there must be something more to this. Maybe there was some sort of miscommunication or mistranslation that erroneously labeled them as deities.” But for the Eastern audience that the games were originally created for, they should make a lot more sense and not seem like such a radical concept at all.

Ever since they first appeared in Ocarina of Time, there have been a lot of questions regarding the divinity of both Jabu-Jabu and the Deku Tree, though Jabu-Jabu especially. Many fans ask just how they qualify as deities. They are by no means gods as Western audiences understand. They live and die, they are tangible, physical, breathing beings living in Hyrule like any other mortal race. “Clearly,” the Western audience must be thinking, “there must be something more to this. Maybe there was some sort of miscommunication or mistranslation that erroneously labeled them as deities.” But for the Eastern audience that the games were originally created for, they should make a lot more sense and not seem like such a radical concept at all.

According to what I’ve seen from many fans, Lord Jabu-Jabu cannot be accepted as any form of deity since it appears to be nothing more than a large fish. They question why Nintendo would call this creature the patron deity of the Zora tribe. Accepting a creature like Jabu-Jabu as a god is especially difficult for gamers and roleplayers who play fantasy games where player-characters and NPCs alike casually throw around magic spells and control seemingly godlike powers. For many Western players, a god absolutely has to be much, much more than that for them to justify that title. They must have might of totally incalculable levels beyond all human comprehension. They must exist on a level above what a player-character is ever capable of achieving to maintain that difference between what is mortal and what is godlike. Even in Zelda it’s obvious that Jabu-Jabu and the Deku Tree are easily threatened by Ganondorf and must be saved by Link, so it’s unbelievable that they could be deities.

Clearly something was lost in translation.

One source of confusion is the preconceived notion Western players seem to have about the nature of a deity. The common western thought on a polytheistic deity mostly comes from the Greek pantheon and Hellenistic belief. To the Greeks, the gods and goddesses were distinct separate beings with individual personalities that personify aspects of the universe or other concepts. Each is the prime creator and caretaker of that specific aspect of the natural world, with total authority over it. They are perceived to be immortal but not omnipotent. They are similar to humanity in appearance and personality yet with additional supernatural abilities, and it is the level of these abilities that elevates them to a much higher status. They are fallible and prone to passion and human emotion, but are still the absolute administrator of their domain and are always unquestionable and unchallenged. Within their individual fields they are all-powerful. A major aspect of classical Greek literature is the constant reminder that gods are gods, and mortals are mortals; A mortal crossing a god normally meant divine retribution in a big way. This causes most western fans to understand that the gods and their nature are on a level far above that of any ordinary character. To see one as a fallible character that makes mistakes is one thing. But to see one as a relatively mortal terrestrial character capable of being harmed or killed is another entirely, and this never occurred in western theology.

That said, the necessary characteristics to qualify as a god would be different for Eastern players. A Japanese audience would easily gain understanding from their own cultures and religions, particularly Buddhism and Shintoism. Shintoism was the native community-based folk religion of Japan that taught that all natural objects were inhabited by spirits, having evolved from shamanism and nature worship. Buddhism on the other hand was imported to Japan in the 6th century, bringing with it new concepts and philosophies such as deities with anthropomorphic characteristics and a central religious doctrine. Each allows for the other to exist, yet Buddhism was accepted by the Japanese ruling elite and quickly became the court religion, while Shintoism remained in practice as the indigenous folk religion among the commoners in the rural regions. Hence the difference in the more civilized metropolitan Hylians, dedicating their worship to the golden goddesses, while the more rural and unsophisticated Zora dedicate their focus on the local nature spirit of Jabu-Jabu in the form of a native folk religion. This is very reminiscent of the cultural divide between Buddhism and Shintoism.

Kami is a more generic term that can encompass the western concepts of a polytheistic deity, angelic beings, an anthropomorphic spirit of a mountain, or even a deceased person. And can appear in the form of a spirit, an object, a plant, or an animal. Each of these seemingly random and ordinary objects could be considered the “container” of sorts for such a spiritual entity and worthy of worship. Normally these divine containers would be charged with the protection of an area and its people. However there are different degrees of kami, ranging from high deities of heaven to gods of certain places on earth and even further down to a protective spirit of a single house. The more well-known Amaterasu and Hachiman are closer to the common western thought of deities of the sun and war, respectively, and are superior to a tree spirit. Yet all are considered kami under this unique system. They may have great differences in their classification and status, but are considered to be the same type of entity regardless of level of influence. This immediately brings to mind Zelda’s many deities of wildly varying size and shape, as well as importance.

It is not uncommon for a sacred tree to be the local kami of a region, and the earliest shrines were sacred groves where kami were thought to live. A great tree wrapped with a shimenawa, or sacred rope signifying its distinguished nature, is often found near modern shrines and are often considered divine themselves, and not just a representation of a kami. Many local communities have small shrines like these erected for the prosperity of the town. The local shrines are common enough to reappear in many forms of media such as movies or games, even in various manga. Since these are not an uncommon sight, the Japanese audiences would instantly pick up on the meaning behind such places as having sacred trees or objects cared for as a local deity. On a few occasions these have been parodied, often citing the ridiculousness of some villagers worshiping some unusual object or just the absurdity of the object itself.

It is not uncommon for a sacred tree to be the local kami of a region, and the earliest shrines were sacred groves where kami were thought to live. A great tree wrapped with a shimenawa, or sacred rope signifying its distinguished nature, is often found near modern shrines and are often considered divine themselves, and not just a representation of a kami. Many local communities have small shrines like these erected for the prosperity of the town. The local shrines are common enough to reappear in many forms of media such as movies or games, even in various manga. Since these are not an uncommon sight, the Japanese audiences would instantly pick up on the meaning behind such places as having sacred trees or objects cared for as a local deity. On a few occasions these have been parodied, often citing the ridiculousness of some villagers worshiping some unusual object or just the absurdity of the object itself.

Here and here are two comic pages parodying a local village deity of a watermelon set on a Himorogi or altar meant for worship, and is adorned with paper Shide commonly used in Shintoism.

Even as a joke the audience was meant to understand that the people of the village had an oversized fruit as their local protector deity. Though it’s a parody, the point that a deity may come in the shape of an overly unusual inanimate object is still to be accepted by readers. This may come off as more than unusual to a Western reader as they might not understand a protector as an unusual object. There are very few Western analogues to this sort of deification process. The reader is meant to understand that it is the unique qualities of the object in the first place that made it necessary to be deified. Only in this instance, it was a joke in that the villagers made something as wacky as an oversized watermelon their patron deity. This is very similar to what happened in Ocarina of Time, when Jabu-Jabu appeared as little more than an enlarged but still relatively normal fish that the Zoras had titled their protector deity. It was just as strange and unusual to Western thought but still would have made sense to an Eastern player.

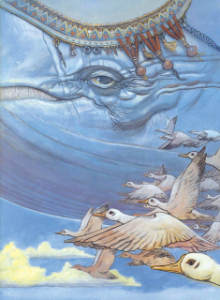

So based on appearance, Jabu-Jabu might clearly be a large fish on both the inside and out, but with the Japanese kami in mind, he might very well be the sacred vessel that houses a divine spirit that is considered the protector deity of the Zora people and their ancestral lands. He is enshrined on an altar and given offerings in the form of fish by his personal caretakers in return for granting continued prosperity to the Zora. Whether this is merely a local custom of the Zora or not is still not entirely known; As the Zora’s Fountain is the water source for all of Hyrule, feeding all the rivers and Lake Hylia, he could very well be the protector deity of all the water of Hyrule, guarding the water for the entire region of Hyrule and not just existing as a protector for the Zora people.

Jabu-Jabu is not alone as a deified aquatic creature within the Zelda series. There have been numerous similar creatures like the Ocean King, Levias, and even the Wind Fish. There may yet be some relation that has yet to be revealed. Evidence of the divine nature of all three of these characters is a little more obvious than that of Jabu-Jabu. They each display not only the power of speech but also a host of other magical capabilities, although they often still require the help of a young hero in times of need. Regardless of their more obvious stature they are still generally incapable of defeating whatever threat that comes to their realms.

Jabu-Jabu is not alone as a deified aquatic creature within the Zelda series. There have been numerous similar creatures like the Ocean King, Levias, and even the Wind Fish. There may yet be some relation that has yet to be revealed. Evidence of the divine nature of all three of these characters is a little more obvious than that of Jabu-Jabu. They each display not only the power of speech but also a host of other magical capabilities, although they often still require the help of a young hero in times of need. Regardless of their more obvious stature they are still generally incapable of defeating whatever threat that comes to their realms.

In The Wind Waker there is a similar creature known as Jabun who was said to be the descendent of Jabu-Jabu. He was another large fish creature that was largely considered to be divine in origin and was a servant to the goddesses. Jabun was also described as a water spirit. This description, particularly the term “spirit”, could in fact be referring to the kami or similar type of being, that the physical fish creature housed.

It is no surprise that as a game developed in Japan, Ocarina of Time would come with a few cultural references lost in translation. The developers have their own culture to draw from when developing the people of Hyrule, and the Zora and their patron deity would be no exception. The concepts included in this game not only introduce a new perspective to foreign audiences but also may have introduced some of the culture as well. Interestingly, as the series continues we may just see some more interesting aspects like this which might have us asking questions and looking for answers in the same way. Either way, I hope now you can more understand how Jabu-Jabu — and similar deities like the Deku Tree — could be considered gods.

Shinto & Shintoism Guidebook, Guide to Japanese Shinto Deities (Kami), Shrines, and Religious Concepts

All comic images are owned by Rumiko Takahashi.

~~~Recent Content Updates~~~