Piece of Heart: Lost Boys and Evil Ploys

Posted on February 20 2015 by Alexis S. Anderson

Welcome to the sixth installment of Piece of Heart, where we look at The Legend of Zelda series through the eyes of a literary professor and examine how its literary elements enhance the gaming experience. This week’s lesson is titled “Hanseldee and Greteldum” so we’ll scour the Zelda series in search of parallels to fairy tales (oddly enough I found none alluding to Hansel and Gretel, nor Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, so I changed the title rather than be misleading).

Welcome to the sixth installment of Piece of Heart, where we look at The Legend of Zelda series through the eyes of a literary professor and examine how its literary elements enhance the gaming experience. This week’s lesson is titled “Hanseldee and Greteldum” so we’ll scour the Zelda series in search of parallels to fairy tales (oddly enough I found none alluding to Hansel and Gretel, nor Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, so I changed the title rather than be misleading).

The land of Hyrule connects with the real world when it takes a page from our favorite bedtime stories. A young boy clad in green with an unruly shadow and fairy companion, a girl who disguises herself as a male warrior in order to protect her family and homeland, fairies who aid a hero on his way to slay a dragon and wake a sleeping princess– The Legend of Zelda sounds like something straight out of Disney!

Alright, fairy tale parallels are pretty simple– if authors want readers to collectively understand a reference, they use a fairy tale. Because most children have fairy tales recounted to them as bedtime stories, or shoved in their faces by our Disney overlord’s, the tales are universally understood allusions. These tales can be used for resonance, analogies, or plot structures; and because fairy tales are so straightforward nearly everyone is going to react the same way to their use. Even the slightest reference will be picked up by readers because fairy tales are internalized pieces of literature. These references can also be made to add depth, emphasize a theme, lend irony, or make social statements.

We’ll start off easy, Peter Pan! Shigeru Miyamoto admitted to the French publication GameKult that Link was inspired by Peter Pan right from the beginning which is why he ended up with pointy ears and a green tunic. But the parallels don’t stop there; the Kokiri in Ocarina of Time don’t age, much like the inhabitants of Neverland. Tinkerbell was just as sassy and annoying, yet devoted, as any of Link’s floating fairy companions. And Link even has to fight Dark Link who would stand in for Peter Pan’s shadow, which Pan had to wrestle with in the Disney adaptation. In both fights it’s hard for the tunic-clad hero to gain the upper hand. I mean honestly, in Link’s Awakening there’s even a promiscuous mermaid much like those in Neverland’s Mermaid Lagoon. None of them wear proper bikini tops, and Martha the mermaid in Link’s Awakening gives hers to Link. Peter Pan plays a flute for Pete’s sake!

We’ll start off easy, Peter Pan! Shigeru Miyamoto admitted to the French publication GameKult that Link was inspired by Peter Pan right from the beginning which is why he ended up with pointy ears and a green tunic. But the parallels don’t stop there; the Kokiri in Ocarina of Time don’t age, much like the inhabitants of Neverland. Tinkerbell was just as sassy and annoying, yet devoted, as any of Link’s floating fairy companions. And Link even has to fight Dark Link who would stand in for Peter Pan’s shadow, which Pan had to wrestle with in the Disney adaptation. In both fights it’s hard for the tunic-clad hero to gain the upper hand. I mean honestly, in Link’s Awakening there’s even a promiscuous mermaid much like those in Neverland’s Mermaid Lagoon. None of them wear proper bikini tops, and Martha the mermaid in Link’s Awakening gives hers to Link. Peter Pan plays a flute for Pete’s sake!

Anyway, clear parallels but what are they all for? Well we know Peter Pan is a fearless adventurer who would go to any length to save those he cares about, so we automatically apply those feelings to Link. We also automatically associate the antagonist in a Zelda title with Captain Hook and transfer those negative feelings. The kid-run atmosphere of Neverland connects with the main Zelda audience, giving children a feeling of control and power despite the daunting task. The wonder of flying through neverland resonates with the exploration of Hyrule to make for a more immersive adventure; we already sort of know that the hero will prevail because Peter Pan did, so that winning spirit spurs the player on. And in Ocarina of Time, we also sadly realize beforehand– whether we choose to acknowledge it or not– that the Hero ends the adventure pretty much alone. Whether this makes the moment easier to deal with, as in my case, or doubly troubling is a personal affliction.

Moving on: Link, give me the Triforce! Aladdin, give me the lamp! I need it so that I can wish for limitless power! Yeah most antagonists in the Zelda series are evil sorcerers who trick the King into trusting them so that they can ultimately usurp the throne and harness the power of the Triforce and take over even more territory. Sound familiar? Well it should because Zelda antagonists are dead ringers for the evil Jafar. Link and Aladdin are parentless diamonds in the rough whom the sorcerers have to get through before they can claim their wish for power; whether it be the Triforce granting the wish like in Wind Waker or a genie from a lamp doing so. Just like Jasmine, Zelda never trusts the sorcerers and the sorcerers always want the Princess “out of the way” once they come into power.

With this many fitting parallels I almost want to say that Aladdin serves as a frame story for the Legend of Zelda, at least Ocarina of Time or Wind Waker. In both, Zelda is disguised at some point either as Sheik or Tetra, just like Jasmine plays a beggar. In Ocarina, Link has to escape Gerudo Desert and the Ice Cavern which are similar settings to those Aladdin had to escape, and there was even a merchant on a flying carpet in Gerudo. The parallels don’t correlate well with the original story, but these games trail the Disney film by over five years making a borrowed plot structure plausible. A big chunk of Aladdin’s plot is missing though, because the Legend of Zelda isn’t a love story while much of Aladdin surrounds his becoming worthy of marrying the Princess. In fact this may be where much of the ‘Zelink’ dynamic comes from, because though the two interact more in these titles than say Twilight Princess, they aren’t childhood friends this time so the Aladdin and Jasmine love story resonates with players here.

With this many fitting parallels I almost want to say that Aladdin serves as a frame story for the Legend of Zelda, at least Ocarina of Time or Wind Waker. In both, Zelda is disguised at some point either as Sheik or Tetra, just like Jasmine plays a beggar. In Ocarina, Link has to escape Gerudo Desert and the Ice Cavern which are similar settings to those Aladdin had to escape, and there was even a merchant on a flying carpet in Gerudo. The parallels don’t correlate well with the original story, but these games trail the Disney film by over five years making a borrowed plot structure plausible. A big chunk of Aladdin’s plot is missing though, because the Legend of Zelda isn’t a love story while much of Aladdin surrounds his becoming worthy of marrying the Princess. In fact this may be where much of the ‘Zelink’ dynamic comes from, because though the two interact more in these titles than say Twilight Princess, they aren’t childhood friends this time so the Aladdin and Jasmine love story resonates with players here.

I personally equate Ocarina of Time Zelda with Mulan though, because as stated earlier both are girls who disguise themselves as male warriors in order to protect their families and homeland. So of course, Sheik would be Ping. In Mulan’s original poem she has weapons training prior to her entry into the war, which works as Impa presumably trained Zelda during the seven years of Link’s holding in the Chamber of the Sages. Assuming Zelda was a little over the age of ten at the start of Ocarina, her taking on Sheik’s persona fits Mulan’s going into the military fully trained at age eighteen. In the Disney story, Mulan’s identity is exposed before she defeats Shan Yu in her true female form using a firework cannon; similarly Zelda is seized by Ganondorf and in the end aids Link using her light arrows– a light arrow, a firework cannon, I mean who can tell the difference?

This parallel falls under the category of a social statement, in addition to a foreshadowing and resonance tool. If the comparison was made early on by a player, which is unlikely but possible, then Sheik’s mysterious ways would make a lot of sense and his true identity wouldn’t be a shock to the player. As for resonance, players will look back on Sheik as a noble or honorable character rather than think Zelda cowardly for hiding from her enemy; the connection helps players to better understand Zelda and Sheik’s motives. The social statement is a feminist one stating that female characters– even supposedly dainty Princesses –can be strong and heroic. The statement isn’t clearly made in Ocarina of Time, because the focus is on Link saving the day and rescuing the Princess, but the intent was there and the Mulan parallel helps to get the point across.

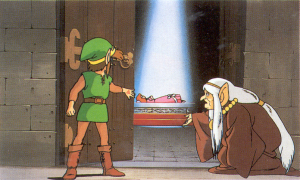

Sleeping Beauty calls to mind the Zelda from Zelda II: The Adventure of Link who was put into endless sleep by a wizard because her brother was mad that she wouldn’t tell him where the rest of the triforce was. Similarly, the sorceress Maleficent cursed Princess Aurora to prick her finger at age sixteen (Princess Zelda was seventeen) and die, though the curse was weakened so she would only sleep. Zelda’s brother is overcome with grief much like Aurora’s father was. And though dragons don’t stand as the bosses of every palace in Zelda II, one does guard the Hidden Palace and Link must slay him on his journey– much like Aurora’s Prince Phillip had to. In the Grimm brothers’ Little Brier-Rose no Prince could access the castle save but one, much like no hero could awaken Zelda save for the chosen one worthy of the triforce.

Sleeping Beauty calls to mind the Zelda from Zelda II: The Adventure of Link who was put into endless sleep by a wizard because her brother was mad that she wouldn’t tell him where the rest of the triforce was. Similarly, the sorceress Maleficent cursed Princess Aurora to prick her finger at age sixteen (Princess Zelda was seventeen) and die, though the curse was weakened so she would only sleep. Zelda’s brother is overcome with grief much like Aurora’s father was. And though dragons don’t stand as the bosses of every palace in Zelda II, one does guard the Hidden Palace and Link must slay him on his journey– much like Aurora’s Prince Phillip had to. In the Grimm brothers’ Little Brier-Rose no Prince could access the castle save but one, much like no hero could awaken Zelda save for the chosen one worthy of the triforce.

This allusion doesn’t scream anything at me thematically, but the first two Zelda games also don’t scream coherent-and-involved-plot either, so that might explain the lack of substance. The slumbering princess reference was probably made so that players would better connect with the storyline despite it being underdeveloped. Those who know the Sleeping Beauty story, will be more driven to gallantry because they already associate Princess Zelda with the beautiful and innocent damsel in distress Aurora. They’ll also already have an idea of Link’s bravery as indicated by Prince Phillip’s determination, and automatically romantically connect Link with Princess.

Whew, that was a mouth full! But you get the idea: fairy tale allusions are used for resonance, recollection, plot structure, social statements, and irony. They can be applied to, and do frequently appear in, media outlets across the spectrum– from literary texts, to cartoons, and of course video games.

What do you think of this week’s lesson? Is finding references to well-known fairy tales in Zelda games interesting to you? I hope these analyses helped to add more depth to these already magnificent games, if I’ve missed any references or you’d like to contribute your own analyses, then let your ideas loose in the comments!

Alexis S. Anderson is a Senior Editor at Zelda Dungeon who joined the writing team in November, 2014. She has a JD from the UCLA School of Law and is pursuing a career in Entertainment and Intellectual Property Law. She grew up in the New Jersey suburbs with her parents, twin brother, and family shih-tzu.