Zelda and the Silver Screen: The Antiplot

Posted on September 28 2012 by Legacy Staff

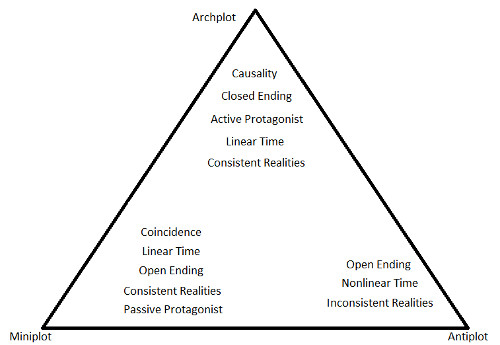

Welcome back. A few weeks ago, we discussed the idea of a film based on the Zelda series, and looked at the plots of Skyward Sword and Ocarina of Time, comparing them to Robert McKee’s definitions of the archplot and the miniplot respectively. This week, we’re going to continue looking at McKee’s plot triangle, focusing on the third type of plot: the antiplot. If you haven’t read the first article in this series, I advise you to go do so now; we’ll be using many of the same terms and ideas, as well as introducing a few new ones, so it’ll be easy to get lost if you’re unfamiliar with what we’ve previously discussed.

Welcome back. A few weeks ago, we discussed the idea of a film based on the Zelda series, and looked at the plots of Skyward Sword and Ocarina of Time, comparing them to Robert McKee’s definitions of the archplot and the miniplot respectively. This week, we’re going to continue looking at McKee’s plot triangle, focusing on the third type of plot: the antiplot. If you haven’t read the first article in this series, I advise you to go do so now; we’ll be using many of the same terms and ideas, as well as introducing a few new ones, so it’ll be easy to get lost if you’re unfamiliar with what we’ve previously discussed.

The antiplot is a very strange plot construction that is very common in postmodern films that seek to “deconstruct” a genre or technique, in that they reverse a lot of the conventions in order to comment on and point out traits specific to that genre or technique. It’s very much a tool used primarily by arthouse films, and as such is rarely seen in mainstream Hollywood movies. So it’s somewhat surprising that the Zelda series gives us such a stellar and well-developed example of the antiplot in none other than Majora’s Mask. Let’s take another look at the plot triangle to get things started.

Last time, we discussed the differences in the mechanisms that govern the plot (causality vs. coincidence), the differences in the behavior of the protagonist (active vs. passive), and the differences in the resolution (closed vs. open). These differences are seen clearly when comparing archplots and miniplots, but antiplots blur the lines somewhat. Unlike the archplot and miniplot, the antiplot seeks to actively distort the standard perceptions of plot. Rather than have a clear story that progresses from plot point to plot point, antiplots are often governed by unrelated incidents that incite completely separate plots. In Wong Kar-Wai’s 1994 Hong Kong film Chungking Express, there are two completely unrelated stories that are connected only by their relation to the titular Chungking Express, a fast food establishment that the characters of the separate plots frequent. The result is a film that seems to be about nothing. It meanders from character to character, with little connective tissue, focusing on their stories and failing (or refusing) to construct a grander plot skeleton that unites all the characters in the film.

This brings us to Majora’s Mask. It has correctly been identified as the Zelda game with the greatest emphasis on sidequests; around half of the game’s content exists as optional sidequests tangential to the main quest. For this reason, we must change the way we look at a Zelda game’s plot for Majora’s Mask: Rather than being the story of Link and his efforts to stop the moon from falling, Majora’s Mask is the story of all the characters Link interacts with throughout his journey. It is the story of Anju and Kafei as much as Link and the Skull Kid, the story of the Postman and of Kamaro as much as the story of the Moon and Majora’s Mask. It is not the story of Link searching for his lost friend; it is the story of Termina, and all the strange and wonderful people who live there. It is for this reason that the story of the game, presented in the interactive manner of a video game, is so powerful: It allows you to interact with these characters as you wish, and to explore the world and the people in it at will, establishing meaningful relationships with each one in turn. It is also for this reason, however, that Majora’s Mask is dreadfully ill-suited to cinematic adaptation. Let’s talk about why.

Review: Plot, Protagonist, and Resolution

One of the best quirks of the antiplot is that while the overall plot of the work fails to resemble any standard plot conventions, the individual plots within bear strong resemblances to the other plot structures. As such, the discussion about the elements that make up archplots and miniplots is still highly relevant in determining the suitability of an antiplot for the medium of film. In almost every case, these inner plots of Majora’s Mask have more in common with a miniplot (like Ocarina of Time) than an archplot (like Skyward Sword).

One of the best quirks of the antiplot is that while the overall plot of the work fails to resemble any standard plot conventions, the individual plots within bear strong resemblances to the other plot structures. As such, the discussion about the elements that make up archplots and miniplots is still highly relevant in determining the suitability of an antiplot for the medium of film. In almost every case, these inner plots of Majora’s Mask have more in common with a miniplot (like Ocarina of Time) than an archplot (like Skyward Sword).

Majora’s Mask is undoubtedly a game governed by coincidence over causality; like Ocarina of Time, each of Majora’s Mask’s four regions features a separate plot independent of the other regions. While they must be played in sequence (in most cases) due to the obstacles that require the use of various items from the previous region, there is no causal link leading from one region to the other. Link’s actions in Woodfall do not affect anything in Snowhead, Great Bay, or Ikana Canyon. Similarly, the interactions of the citizens of Termina are governed by coincidence over causality: While Link’s interactions with some characters will trigger different interactions, it is primarily through the coincidental meeting of characters that these changes occur. For instance, the Postman’s involvement with the Anju and Kafei plot is wholly coincidental — he is simply performing his duty. That Link’s delivery of the Special Delivery to Mama happens to solve his inner conflict is coincidental; it’s not related to the Special Delivery or Link’s prior actions, it’s simply the act of needing the letter delivered. The plots run tangential to each other, and intersect at this one point by coincidence, not causality. That the game’s many inner plots are ultimately governed by coincidence results in the game being ill-suited for cinematic adaptation in the same way as Ocarina of Time: The segmented feel that will result from the lack of a single driving force throughout the entire film. This is not conducive to the fantasy epic genre that a potential Zelda film would certainly fall into, and as such the film would ultimately feel aimless or “about nothing” as we mentioned earlier.

Majora’s Mask’s ending is also similar to the ending of Ocarina of Time in that it is a mostly open ending. Given what I said earlier about Majora’s Mask being about Termina and the people within it rather than the central conflict of the game itself, the saving of the world from its imminent destruction by the Moon leaves a great deal of emotion unresolved. The game nicely wraps up the plot threads of the Happy Mask Salesman, Tatl and Tael, the Skull Kid and the four giants, and Link himself, but what of the other citizens of Termina? How do they react to the sudden saving of their world? How will life continue for them? It’s this significant lack of emotional resolution that secures Majora’s Mask’s open ended status, and this lack of resolution that will leave the audience expecting more (and, as we’ve seen in the Zelda community, it does leave many fans wanting more as a sequel to the game is fairly often requested). The endings of the inner plots, however, tend to be closed. In most every case, the plot is brought to full emotional resolution. The Postman is allowed to flee having fulfilled his public duties, Anju and Kafei get married just moments before the Moon falls, and Romani and Cremia are saved from “Them”. While the overall plot of the game leaves their fates following the world’s saving uncertain, their fates within the three-day period are clearly determined and resolved.

The protagonist is where Majora’s Mask doesn’t really line up with the archplot or the miniplot. Rather than having an active or a passive protagonist, Majora’s Mask really has no protagonist. You play as Link, so you tend to assume Link is the protagonist, but as we’ve said, the central conflict of Majora’s Mask is far from the full story of the game. Link is much less a protagonist and far more the connective tissue. He is the thing that all the people you encounter in the game have in common: They have all met and been helped by a strange boy in green who seemed to occupy four different forms. Unlike the Link of Skyward Sword, this Link doesn’t undergo significant character growth or even show much emotion. Unlike the Link of Ocarina of Time, there is no “coming of age” aspect to this Link’s story (while they may be the same Link, I’m speaking solely of their individual stories in each game rather than the overall story of the single Link). Link here is very much an empty shell that helps all these people as their world comes to a slow end. He is the connective tissue that strings the various stories together into the game’s overall antiplot. So perhaps the various characters in the sidequests can be said to be protagonists, but the problem that arises there is which characters are termed the protagonists? Anju and Kafei? Romani and Cremia? The Goron Elder’s son? With so many sidestories of equal weight and heft, it’s nearly impossible to point to a protagonist in Majora’s Mask. It’s a game without a protagonist, and that makes it very, very difficult to adapt to film. Can you have a film with characters that flit in and out of the main story with smaller character arcs? The lack of a single character that persists throughout the film with which one can empathize is one of the greatest barriers to adapting Majora’s Mask into film.

The protagonist is where Majora’s Mask doesn’t really line up with the archplot or the miniplot. Rather than having an active or a passive protagonist, Majora’s Mask really has no protagonist. You play as Link, so you tend to assume Link is the protagonist, but as we’ve said, the central conflict of Majora’s Mask is far from the full story of the game. Link is much less a protagonist and far more the connective tissue. He is the thing that all the people you encounter in the game have in common: They have all met and been helped by a strange boy in green who seemed to occupy four different forms. Unlike the Link of Skyward Sword, this Link doesn’t undergo significant character growth or even show much emotion. Unlike the Link of Ocarina of Time, there is no “coming of age” aspect to this Link’s story (while they may be the same Link, I’m speaking solely of their individual stories in each game rather than the overall story of the single Link). Link here is very much an empty shell that helps all these people as their world comes to a slow end. He is the connective tissue that strings the various stories together into the game’s overall antiplot. So perhaps the various characters in the sidequests can be said to be protagonists, but the problem that arises there is which characters are termed the protagonists? Anju and Kafei? Romani and Cremia? The Goron Elder’s son? With so many sidestories of equal weight and heft, it’s nearly impossible to point to a protagonist in Majora’s Mask. It’s a game without a protagonist, and that makes it very, very difficult to adapt to film. Can you have a film with characters that flit in and out of the main story with smaller character arcs? The lack of a single character that persists throughout the film with which one can empathize is one of the greatest barriers to adapting Majora’s Mask into film.

Although the overall plot of Majora’s Mask lacks a protagonist, we can see clearly defined protagonists, both active and passive, in the various inner plots. The best example of the active protagonist is Kafei, the man turned into a child by the Skull Kid’s magic. While he has ostensibly accepted his fate as a man in a child’s body, he very outwardly pursues his desire to reclaim the Sun’s Mask he made for his wedding. Conversely, the best example of the passive protagonist is the Postman. While he outwardly continues about his daily routine to the exact second, he inwardly struggles with his desire to flee for his life and his commitment to his job. These are simply the strongest examples of a larger collection of protagonists, active and passive, littered throughout the various inner plots that compose the daily lives of Termina’s citizens.

Time: Linear vs. Nonlinear

Finally, new topics! “Time” in this context deals with the sequence and presentation of events. Archplots and miniplots are almost always going to follow linear time: Their plots are going to be presented in a strict sequence of events from A to B. With Ocarina of Time, that may not seem be the case, since Link travels through time on numerous occasions. What ultimately qualifies it as linear time, regardless of this time travel, is that the time travel does not affect the sequence of events; the past is still before the present, and the game makes a clear distinction between what is the past and what is the present through Link’s age. Nonlinear time, on the other hand, does not make this distinction, and will frequently blur the sequence of events so that the audience is unsure which events take place before which other events. It becomes a mess of a timeline for the audience to figure out. It is a favorite tool of antiplot films.

Majora’s Mask fits this to a tee. While each three-day cycle proceeds from event A to event B with no temporal manipulation, time is wildly inconsistent. Songs like the Song of Double Time or the Song of Inverted Time manipulate the flow of time to make it slower or to skip ahead in 12 hour increments, and of course the Song of Time resets the entire cycle. When you complete a sidequest, did it take place before or after the sidequest you completed in the previous cycle? When the audience is watching the film, will they be able to understand the sequence of events? Unlikely: It jumps around in time and rewinds time so much that there is a constant blurring of the logical sequence of events. Films that do this can be alienating to audiences because they can be hard to follow, and while a film could conceivably drop this aspect of the game and have all of the events take place in a single three day period, it’s fairly inconceivable that it could cover the entire scope of the game’s sidequests in a single three day period, much less the main quest itself.

Reality: Consistent vs. Inconsistent

It goes without saying that fantasy works don’t have to occupy the same reality that we do, otherwise none of them would feature magic, which is a staple of the genre. Zelda is no different: Its reality is clearly distinct from our own. But it is very important for any work to establish its own reality and be consistent with that reality. The presence of magic is fine, but having the magic vary greatly in use and power throughout the work is less so. A reality that is consistent establishes set rules for its world, and the characters interact with other characters and the world itself according to these rules. Archplots and miniplots tend to set these up very well; both Skyward Sword and Ocarina of Time have very consistent worlds that don’t bend their own rules.

It goes without saying that fantasy works don’t have to occupy the same reality that we do, otherwise none of them would feature magic, which is a staple of the genre. Zelda is no different: Its reality is clearly distinct from our own. But it is very important for any work to establish its own reality and be consistent with that reality. The presence of magic is fine, but having the magic vary greatly in use and power throughout the work is less so. A reality that is consistent establishes set rules for its world, and the characters interact with other characters and the world itself according to these rules. Archplots and miniplots tend to set these up very well; both Skyward Sword and Ocarina of Time have very consistent worlds that don’t bend their own rules.

Inconsistent realities, however, frequently twist and bend the rules, resulting in a sense of absurdity that pervades the work. In Majora’s Mask, we can see this inconsistent reality pop up in a number of situations. Perhaps most significantly, we can see it in the masks system. Each mask has its own powers, and wearing a mask will change not only the way that the various people in Termina interact with Link, but also the way Link interacts with the world of Termina itself. The four transformation masks perhaps alter things the most severely, as they completely change the way Link moves and fights, as well as the way people in the world perceive him. In most cases, they think he’s a different character entirely. When a Goron or a Zora, Link is mistaken for Darmani and Mikau, respectively. This creates a discrepancy where Link, rather than being himself, is filling the roles of Darmani and Mikau when he wears the masks. This is less of a concern in game form, because as the player you are constantly aware that you are Link, but in the case of a film where there is a greater disconnect between the viewer and Link, this discrepancy will be far more prominent. As a result, viewers may mistake Link’s different forms as different characters entirely, rather than simply the same character wearing masks that change his appearance.

McKee uses Jean-Luc Godard’s film Weekend to illustrate inconsistent realities very well: At one point in the film, a bunch of Parisians burn the author of the classic novel Wuthering Heights for no discernible reason, without provocation, and make no mention of it throughout the rest of the film. The way the characters interact changes for a brief moment as they murder a famed novelist, and then snap back to the way they were before that moment. This moment of sheer absurdity is a glaring indicator of the inconsistent reality of the film. Such a moment also exists in Majora’s Mask: The hand in the toilet of the Stock Pot Inn. Despite previous interactions with characters being mostly rational, this moment is unexplained. Why is he in the toilet? Why does he need paper? We can figure out what he wants, but nevertheless it remains a completely absurd moment that is not referenced again, has no build up or consequence, and remains unexplained.

The most significant example of inconsistent reality in the game is the Song of Time itself. Rewinding the events of the game and then replaying the same three days, but interacting with the same characters in different ways is a textbook inconsistent reality. This is so difficult to adapt because the film will feel absurd and aimless due to the constantly shifting means of interaction. While some films have done the “rewind time and replay the events” aspect — most significantly Run Lola Run — they inevitably come off as absurd and are most well-suited to science fiction where such a rewind is explained with technobabble. In addition, the events that are replayed in these types of films are often the same events with slight variations; Majora’s Mask features different events in each rewind, and while there are commonalities and characters that you will interact with multiple times (typically the residents of Clock Town), the bulk of the events will be different from the events of the previous cycle. The film would have great difficulty maintaining the idea of the cycles and the Moon’s position while still portraying different events each cycle.

Conclusion

The antiplot is a powerful device for character development, because the reversal of the classical design inevitably results in an increased emphasis on characters and not the events. It is, however, ill-suited to film due to the tremendous time requirements necessary to develop things in a logical manner and to include the many tangential plots that center on the focus of the film.

The antiplot is a powerful device for character development, because the reversal of the classical design inevitably results in an increased emphasis on characters and not the events. It is, however, ill-suited to film due to the tremendous time requirements necessary to develop things in a logical manner and to include the many tangential plots that center on the focus of the film.

So where do antiplots belong? Are they doomed to be very tightly written arthouse films, forever escaping mainstream acceptance? Are they going to remain highly praised games that develop an engaging world? Or is there another home for them?

I argue that there is, in fact, a place for antiplots to thrive: Television. Television is a wonderful place for long format stories — especially antiplots — because of serialization. Because you can split a larger story into many smaller segments, a serialized format will flow a lot better. Three episodes devoted to the Anju and Kafei storyline, for example, would be much preferred to trying to cram it all into a 20 minute period within a larger film, because it allows much more time for character development as well as allowing the creative team to reign in the focus on just those characters for the arc, rather than having to keep the main conflict of the film running.

I’ve said it a few times now: Majora’s Mask is about Termina, and the people who inhabit it. That’s a very large and complex subject for any artistic medium to capture, and the game does it well. A purely visual, non-interactive medium would have a hard time doing so, but I think it’s very much up to the task. It’s certainly not without precedent: Serial dramas such as HBO’s The Wire, which is very much about the city of Baltimore as a whole and the problems plaguing the city, have garnered much acclaim and done justice to their subject matter. Can a great Majora’s Mask adaptation be made? I believe it can.

But the question of will it be made –- or, rather, should it be made –- remains very much up for debate.