Shigeru Miyamoto Discusses Creativity, Curiosity and Game Design In A Recent Interview

Posted on December 30 2020 by Sean Gadus

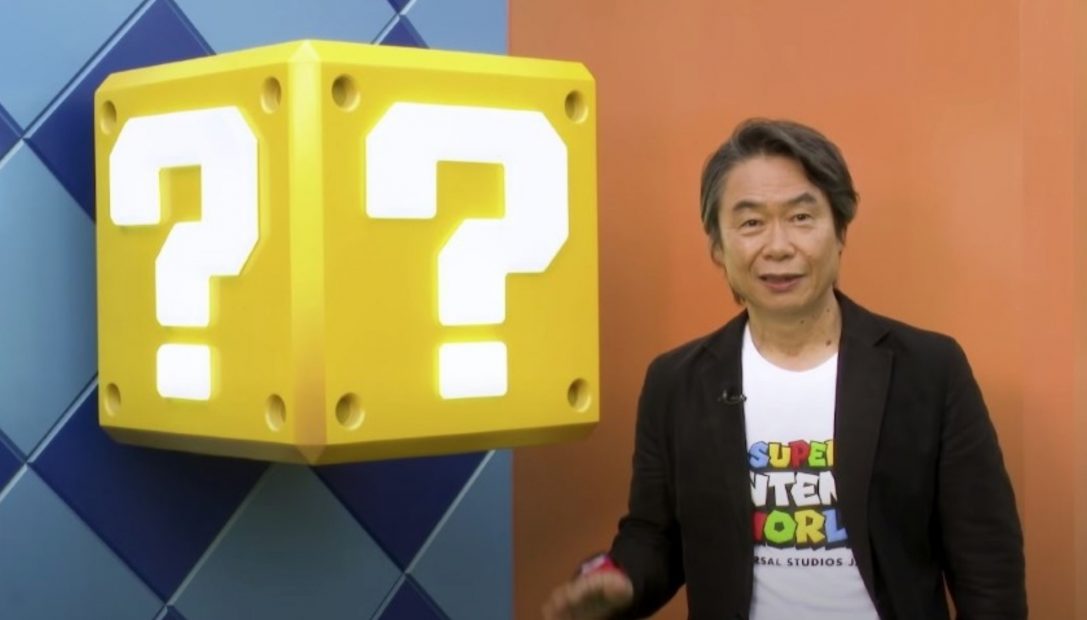

Shigeru Miyamoto is one of most successful and iconic figures in the video game industry. The innovative designer has been a part of Nintendo since 1977 and in the past four decades he has helped create iconic games like Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda. For much of his life, Miyamoto has been a integral part of Nintendo, working as a part of the company through both success and failure.

Miyamoto’s long career in video games, along with his pioneering spirit, make him an excellent subject for interviews. In a recent piece for The New Yorker, the sixty-eight year old gave a wide-ranging interview to Simon Parkin that touched on both the personal and professional aspects of his life. Some of the most interesting areas of the interview were Miyamoto’s thoughts on creativity, curiosity, and game design.

In a discussion about video game design and the space games occupy in a person’s life, Miyamoto discussed the challenges of designing a game and engaging the player:

Parkin: I believe in video games as a medium, and believe they can often tell us things about ourselves that are different from the insights offered by literature or film. There’s also a part of me that recognizes they can occupy a bit too much space in a person’s life. They are demanding and alluring; the obsession they inspire can squeeze out important things. Your job, usually, is to keep players engaged. Do you ever feel a tension between that role and the responsibility of putting things into the world that don’t diminish people?

Miyamoto: It’s kind of hard to build a game where the player can quit anytime. Human beings are driven by curiosity and interest. When we encounter something that inspires those emotions, it’s natural to become captivated. That said, I try to insure that nothing I make wastes the players’ time by having them do things that aren’t productive or creative. I might eliminate the kinds of scenes they’ve seen in every other game, or throw out clichés, or work to reduce loading times. I don’t want to rob time from the player by introducing unnecessary rules and whatnot.

The interesting thing about interactive media is that it allows the players to engage with a problem, conjure a solution, try out that solution, and then experience the results. Then they can go back to the thinking stage and start to plan out their next move. This process of trial and error builds the interactive world in their minds. This is the true canvas on which we design—not the screen. That’s something I always keep in mind when designing games.

A sense of curiosity and agency have long been an important part of Miyamoto and Nintendo’s overall design philosophies. Classic games like The Legend of Zelda (1986) were designed so that the player could forge their own path without the designer holding the player’s hand and showing the player exactly where to go. Looking at the original Zelda game in comparison to later games like Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword (games produced but not directed by Miyamoto), there is an argument to be made that the early hours of the later Zelda games were slowed down by what Miyamoto calls “introducing unnecessary rules”. The original Zelda feels like a very pure distillation of Miyamoto’s philosophy, which may be why the designers of Breath of the Wild look back at it as a source of inspiration.

Additionally, Miyamoto’s love of curiosity and his problem solving process can be reflected in the Zelda team’s approach to Breath of the Wild‘s puzzle design. The Divine Beasts were designed in such a way that players could experiment with the layout of the dungeons and their configurations with almost no restrictions. The four Divine Beasts allow the player to identify the problem or task, experiment with solutions, and see if their strategies are a solution to the puzzle. Nintendo adhered very closely to Miyamoto’s design philosophy for the Shrines and Divine Beasts of Breath of the Wild, which allow for very fluid problem solving and experimentation.

When discussing game design as a process, Miyamoto insists that games need an element of the familiar and unfamiliar to be successful:

Parkin: I’ve always thought that there’s something divine about game-making. You’re conjuring a world, defining the rules of a reality, and then placing little characters into that reality. Has being a game-maker ever led you to ponder the rules of this universe?

Miyamoto: Not particularly, but when I’m trying to create a game world, I like to work on action, movement. Within that experience, there needs to be a mix between what is real and what is not. There has to be a connection to our real-world experience, so that when you make a move in the game it feels familiar but also, somehow, different. To achieve that harmony, you need a dash of truth and a big lie to go along with it. That’s the kind of game I try to create. You take things you’ve experienced in your life, sensations or feelings, and then try to conjure them in the game world.

The aforementioned statement about connecting to “our real-world experience” brings to mind Miyamoto’s previous comments about some of his inspirations for the original Zelda game. Miyamoto has shared that aspects of The Legend of Zelda were inspired by his childhood exploration of the countryside of Japan and the discovery of small caves during his adventures. This sense of wonder and discovery are something that Miyamoto looks to capture in his projects.

Reading this statement, I find myself wanting to look back at all the games that Miyamoto has worked on and try to find the familiar and unfamiliar in each of these projects. Especially in Miyamoto’s early projects, which had major design limitations on controls and graphics/sprites, it could be enlightening to see about how this philosophy may have helped Miyamoto and his counterparts create the games that are now beloved by millions of fans.

Overall, the interview covers a wide range of topics and is definitely worth reading in its entirety. At sixty-eight years old, it is unclear how many years video game fans will have with Mr. Miyamoto before he leaves Nintendo or retires from game design. Because of this, the interview feels like a real treat for fans. Let’s hope that Shigeru Miyamoto continues to leave a mark on gaming for many years to come!

What are your thoughts on Miyamoto’s comments on creativity, curiosity, and game design? Are there specific places where you see these ideas reflected in his work at Nintendo? Let us know what you think in the comments!

Source: The New Yorker

Sean Gadus is a Senior Editor at Zelda Dungeon. His first Zelda game was Ocarina of Time, and he loves all of the 3D Zelda games from 1998-2011. The final battle of Tears of the Kingdom is one of his favorite final battles in the entire series. He wants to help build a kinder, more compassionate world. You can check out his other written work at The-Artifice.com.