Piece of Heart: …So Does Season

Posted on May 08 2015 by Alexis S. Anderson

Welcome to the eleventh installment of Piece of Heart, where we look at The Legend of Zelda series through the eyes of a literary professor and examine how its literary elements enhance the gaming experience. This week’s lesson is titled “…So Does Season.” Similar to geography, the season during which a game takes place has a profound affect on the overall theme of the adventure. For instance, Winter usually denotes death and hopelessness, so the despair surrounding Queen Rutela’s death and the disappearance of her only heir was elevated in Twilight Princess by the temporary winter of the then-frozen Zora’s Domain (here we can see how geography and season act hand-in-hand).

Welcome to the eleventh installment of Piece of Heart, where we look at The Legend of Zelda series through the eyes of a literary professor and examine how its literary elements enhance the gaming experience. This week’s lesson is titled “…So Does Season.” Similar to geography, the season during which a game takes place has a profound affect on the overall theme of the adventure. For instance, Winter usually denotes death and hopelessness, so the despair surrounding Queen Rutela’s death and the disappearance of her only heir was elevated in Twilight Princess by the temporary winter of the then-frozen Zora’s Domain (here we can see how geography and season act hand-in-hand).

Of course Spring, Summer, and Autumn are also host to their own emotional and physical associations. The season in a Zelda title can greatly reflect the mood of the game, and knowing how to spot these seasonal patterns will further aggrandize the game’s plot.

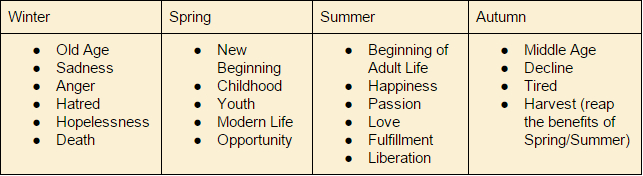

Using the seasons to enhance a story works well because seasons connect with the human experience; there’s always death, rebirth, growth, and harvest just as there’s a natural order of Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. Below I’ve provided a table of the seasons and their typical associations in literature; most of these you’ll realize you already subconsciously connected that season with. Because the usual seasonal attributes are so ingrained in us, seasons are the easiest literary device to use ironically. For instance, someone dying in the middle of the Summer will have a stronger impact on a reader because one sees the Summer as the time for progression and instead the character’s life is stopped in its tracks.

Let’s begin by examining one of the most emotionally taxing games of the series, Majora’s Mask. The game takes place in early to mid-Fall as evidenced by the Carnival of Time’s role as an event at which to pray for a good harvest; harvest festivals usually take place around the end of September. I think decline fits Majora’s Mask best from the Autumn category, as the moon begins to fall and the town shifts into disarray. Link is winding down from Ocarina of Time which would’ve been his summer-era because of his experience as an adult and the fulfillment of vanquishing Ganondorf, so to say Link is tired and his life on the decline would make sense. As mentioned, Clock Town begins to deteriorate as every day more and more people flee. If Kafei and Anju aren’t aided by Link, then the love characterized by summer is lost as well. In terms of harvest, Skull Kid is reaping what he has sown in response to his harassment of the townsfolk, now that he’s the one being pushed around by Majora with no regard for his well-being. The game being placed in the fall gives an inclination as to the decay that is to come right-off-the-bat and gives a natural resonance as the progression into desolation continues to unravel.

To continue with Majora’s Mask, Snowhead’s Winter in particular struck me as seasonally accurate. The Gorons there are the epitome of hopelessness and this stemmed from the death of Darmani. He told Link, “I was fine until I marched off to Snowhead by myself, hoping that I could drive off a demon. It had been wreaking havoc on Goron Village…Then the blizzard at Snowhead blew me into the valley…” A valiant warrior was cut down in his prime and his people left defenseless and in denial about their hero’s disappearance. To further support this idea of hopelessness, the Goron Elder has also gone missing leaving his young son wailing and in tears. The old have gone off and presumably died (even though we know the Elder makes it back), and the biggest image of youth in the Village is incapacitated by grief– that’s a Winter if ever one there was.

To continue with Majora’s Mask, Snowhead’s Winter in particular struck me as seasonally accurate. The Gorons there are the epitome of hopelessness and this stemmed from the death of Darmani. He told Link, “I was fine until I marched off to Snowhead by myself, hoping that I could drive off a demon. It had been wreaking havoc on Goron Village…Then the blizzard at Snowhead blew me into the valley…” A valiant warrior was cut down in his prime and his people left defenseless and in denial about their hero’s disappearance. To further support this idea of hopelessness, the Goron Elder has also gone missing leaving his young son wailing and in tears. The old have gone off and presumably died (even though we know the Elder makes it back), and the biggest image of youth in the Village is incapacitated by grief– that’s a Winter if ever one there was.

Now, I feel obligated to talk about Oracle of Seasons in this installment, alas I have not played it (though I do have it purchased and waiting patiently for me on my 3DS). But because we needed a solid example for Spring, I watched some walkthroughs and will do my best to flesh this thing out. In Oracle of Seasons Link must have the Rod of Seasons blessed by the four Spirits of Season so that he can manipulate the seasons to take down the game’s antagonist, Onox. The Spirits reside in sectioned off areas of the Tower of Seasons, now plunged  into Subrosia, and the Spirit of Spring can be visited after Link has met the Spirits of Winter and Summer respectively.

into Subrosia, and the Spirit of Spring can be visited after Link has met the Spirits of Winter and Summer respectively.

The route to the Spirit of Spring’s chamber is dominated by water, and this greatly supports the idea of Spring as a new beginning; if we remember back a bit, dunks into water are often seen as a baptismal renewals or purifications (which also support the notion of Spring representing youth). This connection is further bolstered by the Spirit’s words to Link, “I am the Spirit of Spring. Rock-hard buds bloom in spring. It is a season of discovery.” Buds stand for the new beginning, and discovery covers the opportunity aspect of Spring. Though the scene fits our ingrained idea of Spring almost perfectly, it strays in one key aspect: it isn’t followed by Summer. Here’s where a bit of ironic-seasonality comes into play. After progressing this far in the game, the fulfillment of a Summer makes logical and chronological sense, but instead the player is left with a lot more to do before facing Onox. So while the player may feel a sense of freedom and hope after meeting with the Spirit of Spring, it is short-lived as our hero’s journey is far from over.

Finally on to Summer, which I’m sure those of you who are students like I am are yearning for at the moment. For this we’ll visit the Wind Waker; we know the game takes place in Summer because the Koroks are conducting their annual Korok Ceremony by spreading Forest Tree seeds, and farmers do the bulk of their planting in the summer. The whole game exudes Summer mainly because it’s a coming-of-age story for many of the characters. Link literally hits the age of the legendary Hero on Outset to mark his soiree into manhood, Tetra is awakened as the descendant of Princess Zelda, Medli and Makar are awakened as Sages, and Prince Komali gets his wings. Love and passion drive Link, among other characters, throughout this adventure. Fulfillment and liberation aptly apply for the King of Hyrule as he’s finally able to vanquish Ganondorf, give this new land a fighting chance, and is freed from regret when going down-with-the-ship as old Hyrule floods. The Summer themes are important in Wind Waker for both the atmosphere of the game and its message, because the player is supposed to feel that in the end the best is yet to come and that New Hyrule will begin to advance at a faster rate following Ganondorf’s defeat; the Summer allows players to look to the future as if it is already in progress.

Finally on to Summer, which I’m sure those of you who are students like I am are yearning for at the moment. For this we’ll visit the Wind Waker; we know the game takes place in Summer because the Koroks are conducting their annual Korok Ceremony by spreading Forest Tree seeds, and farmers do the bulk of their planting in the summer. The whole game exudes Summer mainly because it’s a coming-of-age story for many of the characters. Link literally hits the age of the legendary Hero on Outset to mark his soiree into manhood, Tetra is awakened as the descendant of Princess Zelda, Medli and Makar are awakened as Sages, and Prince Komali gets his wings. Love and passion drive Link, among other characters, throughout this adventure. Fulfillment and liberation aptly apply for the King of Hyrule as he’s finally able to vanquish Ganondorf, give this new land a fighting chance, and is freed from regret when going down-with-the-ship as old Hyrule floods. The Summer themes are important in Wind Waker for both the atmosphere of the game and its message, because the player is supposed to feel that in the end the best is yet to come and that New Hyrule will begin to advance at a faster rate following Ganondorf’s defeat; the Summer allows players to look to the future as if it is already in progress.

That about wraps things up for this week’s lesson, keep that Seasons chart handy whenever you’re playing a video game, reading a book, watching a movie or TV show, or enjoying any other form of media; it’ll give you some insight into the type of events that are likely to unfold and let you feel what the characters are feeling on a more intense level. Just a heads up, this series is winding down, there are some chapters of Thomas C. Foster’s How to Read Literature Like a Professor that don’t apply to Zelda easily enough to warrant full segments, so I won’t be covering them; if there’s a chapter I haven’t covered that you’d really like me to cover, let me know in the comments.

What did you think of this week’s lesson? Do you feel like these Season identifiers apply to the way you personally react to the different seasons? Have you noticed these patterns in other types of media? Share your opinions in the comments and as always don’t be afraid to contribute your own analyses!

Alexis S. Anderson is a Senior Editor at Zelda Dungeon who joined the writing team in November, 2014. She has a JD from the UCLA School of Law and is pursuing a career in Entertainment and Intellectual Property Law. She grew up in the New Jersey suburbs with her parents, twin brother, and family shih-tzu.