Making Zelda Work on Handhelds

Posted on April 12 2015 by Mark Olson

The Legend of Zelda has a long and storied past with mobile systems; indeed, the marriage of the two dates as far back as the series’ fourth game, Link’s Awakening. In this article, I take a look at the design of portable Zelda games by comparing Link’s Awakening, the oldest, and A Link Between Worlds, the youngest, side by side.

The Legend of Zelda has a long and storied past with mobile systems; indeed, the marriage of the two dates as far back as the series’ fourth game, Link’s Awakening. In this article, I take a look at the design of portable Zelda games by comparing Link’s Awakening, the oldest, and A Link Between Worlds, the youngest, side by side.

Now for the obligatory disclaimer: everything in this article was derived from my experience with the game; not yours. In addition, this article is not meant to describe the quality of either game, merely how they minister to handheld play. When taken on their own terms, Link’s Awakening and A Link Between Worlds are both absolutely fantastic games and nothing in this article is intended to say otherwise.

Finally, I would like to briefly thank a commenter by the name of “Soup” who provided the concept for this article in the comment section of my last. Thanks, buddy; I really had a lot of fun with this one. Now, without further ado, onto the article proper.

The dichotomy between Link’s Awakening and A Link Between Worlds is far deeper than old and new; I chose to analyze these two games because they represent two entirely different schools of thought when it comes to making Zelda work on a portable system. Whereas A Link Between Worlds actively designs portions of the game to be enjoyed on the go, Link’s Awakening doesn’t even try; Link’s Awakening looks, feels, and plays like a console Zelda title. Indeed, the development team responsible for the game initially set out to port A Link to the Past to the gameboy before enough new, substantive ideas had been introduced into the pipeline to warrant their own home. This really shows when playing the game. Link’s Awakening is a game that, like all Zelda titles before it, is best enjoyed in your favorite chair with a bag of chips at your side. There is next-to-nothing in this game that is easily enjoyed away from your living room.

A Link Between Worlds feels like the first Zelda game truly tailored to the nature of a handheld console. Everything is cut up into relatively small chunks that allow for the player to accomplish something in the ten minutes they have sitting on the subway. This is clear when one merely glances at the length of the game; there are, by my count, eleven dungeons in the game and yet A Link Between Worlds clocks in at around fifteen hours total for the average player, likely less for anyone who has already played A Link to the Past and is fittingly familiar with the combat. Because the amount of time required to complete objectives is far shorter in A Link Between Worlds than it has ever been before, the player can easily pick up the game, make some progress, and then put it back down.

It certainly takes longer to get to a good stopping point in Link’s Awakening, but I would be in remiss if I didn’t mention that a significant portion of this problem may be the responsibility of limitations of the first GameBoy. A Link Between Worlds most certainly benefited from being on the 3DS as opposed to the beautiful brick that is the game boy; save points weren’t hard to come by, but if the player needed to stop their game abruptly and didn’t want to lose their progress, they were able to simply close up their 3DS and pick the game up later. Those who played Link’s Awakening on the original GameBoy had no such luxury; even if you were playing the original cartridge on your GameBoy Advance, the only manner in which one could stop playing and save their progress was to save and quit. The game would reload at the last door a player went through. This worked in a negligible amount of situations. Being forced to save and quit in the middle of a play session could lead to quite a bit of overworld or dungeon exploration being lost. Having to deal with this unfortunate save system encouraged players to continue playing the game for extended periods of time to ensure that they got to a good stopping point before quiting, just as one would play a console game. It’s incredibly hard to separate the benefits of the 3DS from A Link Between Worlds itself, as the majesty that is putting the system into sleep mode most likely covered up problems similar to those found with Link’s Awakening’s save system, but I would argue that the design of the game itself helped with portability.

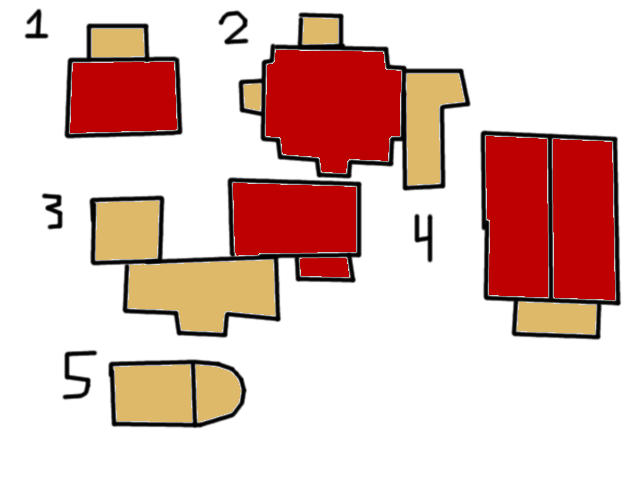

Just because I know you can’t get enough of my rudimentary photo editing skills, I have prepared two pretty pictures for you. This was my attempt to show the first hour long stretch in each game. Obviously, I don’t have the exact numbers detailing what took how long for the average player, but this is what I accomplished in what was (roughly) my first hour with each game. Each spot on the timeline is a notable event, and each of those in red are where the game gives the player a stopping point. Due to Link’s Awakening’s save system, I classified these as whenever the player entered a building and thusly could save and quit without losing progress.

The colors speak for themselves, really. The player could save and quit every twenty minutes or so in Link’s Awakening, whereas A Link Between Worlds allows them to do so roughly every ten minutes.

Outside of the main quest, A Link Between Worlds has a good amount of optional content that can be completed rather quickly. The most obvious example is the multitude of mini-games that offer up a quick dose of instant satisfaction, an element of any Zelda game, not just the portable entries. Link’s Awakening, for example, had a fishing game that allowed the player to have a bit of fun with those extra two minutes they found. A Link Between Worlds offers something far more interesting, however: the handful of optional mini-dungeons scattered through the overworld. These, I find, are much more conducive to a portable Zelda experience than the mini-games. While hunting for red rupees in the treasure chest house can be amusing for a few moments, it doesn’t feel like an actual Zelda game. These dungeons, on the other hand, allow the player to have fun solving puzzles and getting loot just as they would in the game proper, but in a much more concise package permitting on-the-go playtime.

The design of dungeons is also done in such a way so as to ensure that the player is never punished for having to turn the game off. As an example, I’m going to take a look at one of A Link Between Worlds‘ seven Dark World dungeons, Turtle Rock. As soon as the player enters the dungeon, they are greeted with… …an entryway. After that, though, the game introduces a large central chamber with a number of different rooms sprouting off. The genius of this design is that it gives the player a number of options, all of which are self-contained. At the end of each pathway lies a chest with something useful, such as a key used to open another door and its respective pathway. The player can take ten minutes or so to complete one pathway, claim the key, and, here’s the kicker, take it back to the central chamber. Everything comes back to this one room, a room that is only one door removed from Turtle Rock’s exceedingly stylish foyer. As such, when a player turns the game back on after a brief respite, they can immediately put the fruits of their prior labors to use without any backtracking.

As this shows, a primary focus when it comes to moving the Zelda experience to handheld devices is consolidation; the more effective uses you can get out of an area, the better. One of the elements that the Zelda series gets perpetually and magnificently right is ensuring that the player knows how to use an item in an intuitive, unobtrusive fashion. This generally takes the shape of a few easy puzzles utilizing the new equipment in the item room and its surrounding chambers. Enter Ravio’s shop. Everyone’s favorite purple homeless guy-turned shopkeep moves both item acquisition and proficiency testing outside of the dungeons; there’s always a puzzle given to the player before the game allows them to enter a dungeon. This helps turn what would be one large objective with a number of sub-objectives in Link’s Awakening (finish the dungeon), into two smaller objectives (get item and gain entrance to dungeon, finish the dungeon). It accomplishes the same thing; in each scenario the player receives an item, is tested on the proper usage of that item, and has to use their skills to complete a dungeon, but in A Link Between Worlds this process utilizes over world travel to both get the player to the dungeon and ensure that they have a firm grasp on how to handle their new toy, ending in an overall shorter playtime that still hits the necessary marks.

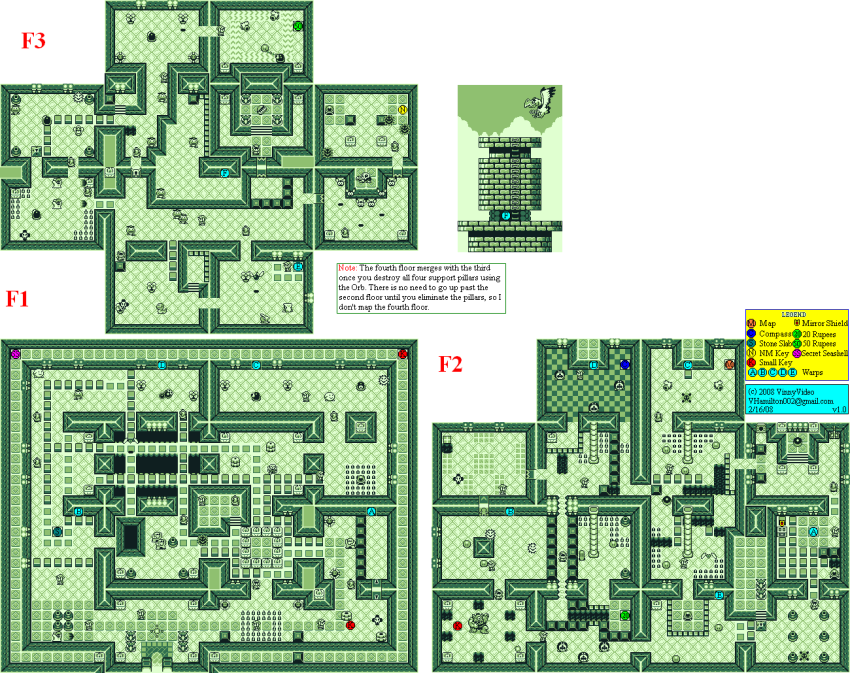

When one compares the dungeons of A Link Between Worlds to those in Link’s Awakening, the difference is obvious; even in the first dungeon of Link’s Awakening, the player is punished for not having a lot of time. The dungeons are all structured exactly as they would have been in A Link to the Past. Turning the game off may mean that the player has to reclaim a significant amount of dungeon contrast. For comparison’s sake, let’s look at maps of both A Link Between Worlds’ and Link’s Awakening’s final dungeons, those being Lorule Castle and Eagle’s Tower, respectively. I was able to get the in-game map of Eagle’s Tower, but I had to draw Lorule Castle. Sorry!

Because of my absolutely atrocious mapmaking skills, it may be hard to see, but, Lorule Castle is divided into segments that force the player to use what is gained at the end of one pathway to enter another. Similarly to Turtle Rock, this means that the player needs somewhere around ten minutes to accomplish something. The dungeon is relatively easy to navigate and not very long, making it well suited for casual, on the go play.

Eagle Rock, on the other hand, is ridiculous. Its size coupled with the main mechanic changing the layout makes it stupid hard to keep track of your location in relationship to everything else while playing for two hours straight, so, for the sake of your mental and emotional state, why would you try and play this in a number of short doses?

Just for kicks, let’s look at the final dungeon of A Link to the Past, Ganon’s Tower. Again, This is from the in-game map. It’s a rather striking comparison with Eagle’s Tower, isn’t it? If anything, Eagle’s Tower is more confusing than Ganon’s Tower due to its main mechanic, bringing the upper floors down in order to change the layout of the dungeon. This really illustrates the design philosophy behind Link’s Awakening: making a console Zelda, but on the gameboy. This philosophy led to the developers creating challenging, labyrinthine dungeons that are a blast to play through when you have a lot of time on your hands, but frustrating to backtrack through.

The point that I’m trying to make with all of this is that the key is consolidation. Making everything take less time is only half the battle; what’s there has to stay true to the heart of the series while keeping portable play in mind. Both Link’s Awakening and A Link Between Worlds have sections apt for a shorter play session, but how each game handles them makes the difference. These portions of Link’s Awakening rarely go beyond a simple mini-game far removed from the main quest, the likes of which one could now find on their iPhone, while A Link Between Worlds makes use of clever level design and short, optional dungeons to shrink the Zelda experience to smaller screens.

What do you guys think? Do you agree with the points I make or have I finally gone and lost it? N o matter your feelings, feel free to share your thoughts in the comments. I’m always open to concepts for new articles, so if you have an idea that you would love to see get turned into an article, fire away.