Linking Masks and Majora – Possession in Majora’s Mask and Noh Theatre

Posted on December 16 2014 by Legacy Staff

How Masks Work in Majora’s Mask

Based on its title alone, it can be assumed that at least one mask in Majora’s Mask will play an important role in the game. Within an hour of play, however, we find out just how prominent and important the motif of masks is in this game. Masks are everywhere: in the opening sequence, hanging on walls, worn upon peoples’ faces, given as gifts. Even the major bosses of the game are described as being “masked” in their onscreen descriptions. The person who assigns to Link and the player the major task of the game – to retrieve Majora’s Mask from Skull Kid – is called the “Happy Mask Salesman.” There are twenty-four obtainable masks in the game, each with a different purpose and effect. Some are used for side quests that yield a life energy increasing heart piece while others transform Link into a completely different species giving him a new body and new abilities.

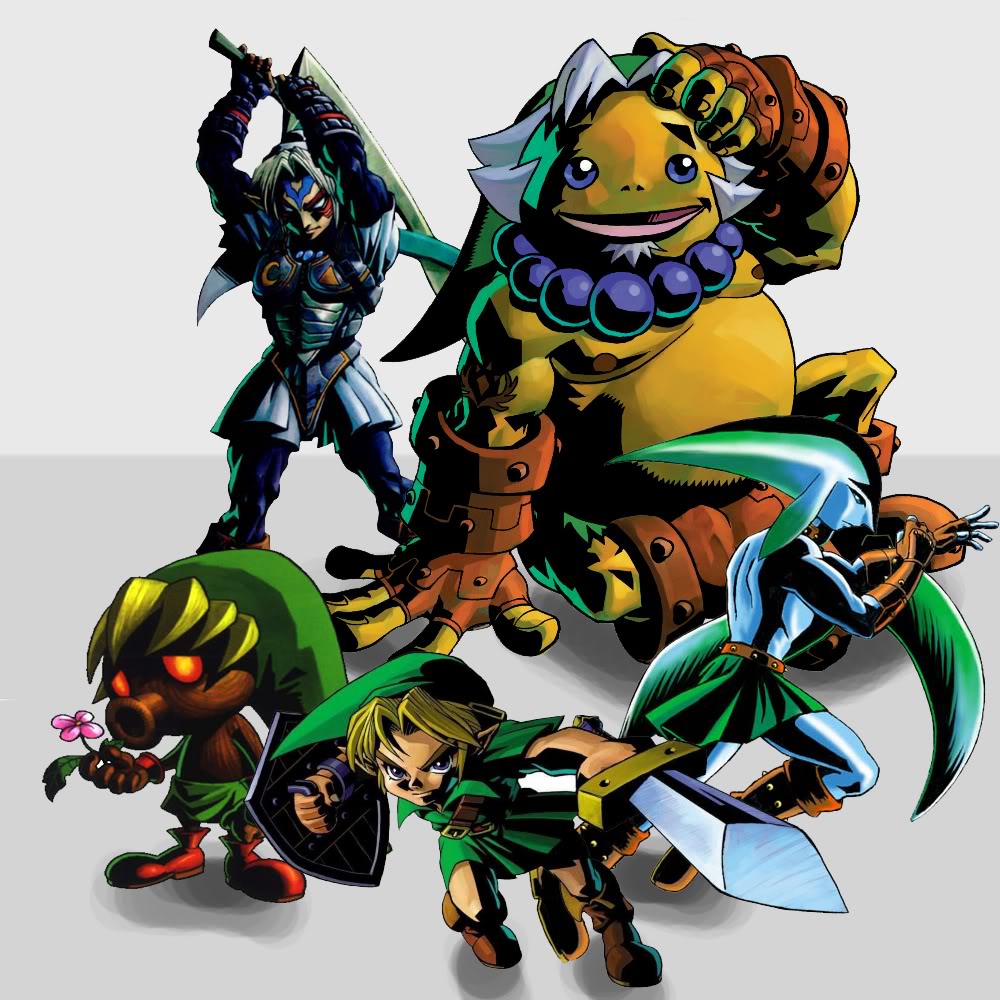

It is with this last category of masks that this article is most concerned. These transformative masks are necessary to complete the game and are obtained during key moments in the game’s narrative. There are five in total and one of them can only be obtained after all of the other obtainable masks in the game have been won through adventuring and side questing. The transformative masks are different from the other masks in the game in that they alter Link’s physical shape and usually give a different set of commands for the player to work with. In one sense, the transformative masks give the player five different Links to play as throughout the course of gameplay.

The first three transformative masks are the most used masks in the game. Each of them is necessary for navigating large portions of the diegesis (i.e. the “game world”) which correspond to the masks themselves: the Deku Mask allows Link to stand on lily pads and launch out of Deku flowers in the Southern Swamp, the Goron Mask allows Link to roll up steep slopes and race over icy terrain in the Snowhead mountain range, and the Zora Mask enables Link to swim swiftly and dive into the deep ocean waters of Great Bay. The other two masks are made less for a particular environment than they are for battle: the Giant’s Mask makes Link grow in size to facilitate the fight with the fourth major boss in the game, Twinmold, and the Fierce Deity’s Mask (or “Oni Mask” in Japanese) transforms Link into a being very much like his adult self which can defeat all of the game’s major bosses with a few strikes of his sword.

One thing to note about these masks is that, while they transform Link’s body and sometimes give him a different set of abilities, the visuals of the game let the player know that he or she is still playing as Link. There is always some part of Link’s clothing that remains green or retains the shape of his hat even with his transformation into a Deku Scrub or a Goron or the Fierce Deity. Yet at the same time, there are definitely aspects of his new body that suggest that he has become someone else. This is seen mostly in the change of musical instruments that comes with each the transformations into Deku Scrub, Goron and Zora but it can also be seen in small elements of Link’s visual appearance.

Yet at the same time, there are definitely aspects of his new body that suggest that he has become someone else. This is seen mostly in the change of musical instruments that comes with each the transformations into Deku Scrub, Goron and Zora but it can also be seen in small elements of Link’s visual appearance.

As a Goron, Link wears the necklace found around the neck of Darmani, the deceased Goron hero whose spirit possesses the Goron Mask. As a Zora, Link’s fins and facial features are tipped with the yellow shades found on Mikau’s body. The unique qualities of the Deku Scrub transformation are somewhat more difficult to pin down visually for the player, but some of the dialogue reveals that Link looks very much like the son of the butler of the Deku Palace in the Southern Swamp: upon winning a race against the butler, he says “Actually, when I see you, I am reminded of my son who left home long ago…Somehow, I feel as if I am once again racing with my son…” and during the end credits, a short scene shows the butler mourning in front of a tree that Tatl the fairy says looks like Link when he is in the shape of a Deku Scrub.

As mentioned, the Fierce Deity’s Mask gives Link a body that looks similar to (and sounds exactly like) his adult self from The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, but his clothes are white, his face has distinct markings, and his sword is different in shape and power from any sword Link has possessed in this or any previous game in the series. The Giant’s Mask yields the least amount of visual difference between Link and the transformation associated with it, yet Link’s voice is different and, due to having to wear the mask, Link’s face at least, appears different.

In addition to the similarities and differences in Link’s appearance with and without the transformative masks, there are cut-scenes associated with each of the transformative masks which emphasize a dramatic change in Link’s character. The first time Link wears each mask, the player is not allowed to skip the cut-scene and is therefore forced to watch. During the cut-scene, Link first puts on the mask, which bears a face that is neutral in the culture associated with the species it represents. Once the mask is put on, however, Link gasps and appears to choke before letting out a cry and revealing his face to the in-game camera.

When Link shows his face to the camera the mask no longer bears the neutral expression it had before it was put on. Instead, it reflects the cry of pain and anguish heard from Link. From the cut-scene and the subsequent transformation, it can be assumed that the mask has become Link’s face just as the body associated with the spirit possessing the mask becomes Link’s new body.

When Link shows his face to the camera the mask no longer bears the neutral expression it had before it was put on. Instead, it reflects the cry of pain and anguish heard from Link. From the cut-scene and the subsequent transformation, it can be assumed that the mask has become Link’s face just as the body associated with the spirit possessing the mask becomes Link’s new body.

The only exception to this recurrent shot is the Giant’s Mask. It is transformative, but it is not obtained in as dramatic a way as the others. In addition to this, it is grouped with the non-transformative masks in the mask select subscreen so it seems to be something halfway between a transformative mask and a non-transformative mask. This doesn’t pose too much of a problem and I’ll address the non-transformative masks later. One thing to note before I go on is the blue “flow” surrounding Link’s face in the above pictures. This can be seen in his transformation into a “giant” in the Giant’s Mask transformation cutscene albeit fro

m a different angle. For the sake of this part of the analysis, let’s group the Giant’s Mask with the transformative masks.

So what exactly is going on in these cut-scenes? As has been proposed before, I submit that it is an act of possession of Link by the spirit of whatever mask he puts on. Upon receiving them, the Goron and Zora masks are described as containing “the spirit of a proud Goron hero” and “the spirit of a legendary guitarist” respectively. The cut-scenes in which Link receives these masks also suggest that the spirits of Darmani and Mikau are sealed within their respective masks. Once Link puts on the Goron Mask or the Zora Mask, he takes on the body of the deceased person whose spirit possesses the particular mask he is wearing. Considering these phenomena and the similarities between these two masks and the Deku Mask, Fierce Deity’s Mask, and Giant’s Mask, it is suggested that each of the transformative masks contains the spirit of a person and, when worn, Link is possessed by the spirit of that person and given the body of that person.

What About Noh?

So, this is probably not a new idea to many people who have played Majora’s Mask. You all have probably surmised that Link is being possessed by the spirits sealed in the masks and that he’s getting the body of that character via possession. Right? Here’s where we begin to ask why. Even though Link has changed his shape for various reasons in other Zelda games both before and after Majora’s Mask, this phenomenon – the use of masks to change form – is unique to Majora’s Mask. It’s especially unique in the amount of different abilities and powers that it gives to Link. Before we get too sidetracked, though, I want to point out that the phenomenon of transformation via masks in the game is strikingly similar to the traditions associated with masks in Noh theatre.

Noh has its roots in the religion indigenous to Japan, Shinto, and the plays in the tradition were, according to Donald Keene, originally “performed in a building belonging to a shrine, and the actors, then as today, were participants in a rite.” Keene says elsewhere that,

“Noh begins with a mask, and within the mask the presence of a god. Before a performance of Okina, the mask to be worn is displayed in the dressing room and honored with ritual salutations. When the actors have filed onto the stage and taken their places, one called the Mask Bearer offers the mask of Okina to another, who prostrates himself in reverence before accepting it. The Okina mask is unlike that for any other role; though its features are those of a benevolent old man and not a fearsome being, they are nonetheless a god’s, and performing this role, devoid though it is of emotion or special displays of technique, is considered so arduous as to shorten the life of the actor…Before the actor makes his entrance he gazes at his masked face in the mirror, and though until that moment an ordinary man…he himself becomes as he stares at the mask a reflection.”

This reverence for the mask used for Okina speaks to several elements of Majora’s Mask (some of which I shall discuss in later articles), but here I wish to emphasize the presence of a spirit within the mask the features of which are those of a god. Once the mask is donned, the actor stares at his face in a mirror located in the dressing room of the theatre, a room which is also called the “mirror room”. Though Keene does not describe in detail what the actor is doing, other scholars have explained what goes on before the mirror mentioned in the above quote. Mikiko Ishii* says that the mirror room is

This reverence for the mask used for Okina speaks to several elements of Majora’s Mask (some of which I shall discuss in later articles), but here I wish to emphasize the presence of a spirit within the mask the features of which are those of a god. Once the mask is donned, the actor stares at his face in a mirror located in the dressing room of the theatre, a room which is also called the “mirror room”. Though Keene does not describe in detail what the actor is doing, other scholars have explained what goes on before the mirror mentioned in the above quote. Mikiko Ishii* says that the mirror room is

“in no way…a conventional dressing room, for it is a place where the actor…puts on his mask and sits in front of the mirror to study the figure that he has made. In so doing he undergoes the process of becoming the character that he is to portray. Reflecting on his image in the mirror, he transcends his merely physical portrayal of the role and is spiritually possessed by the self that he will be personifying.”

Through spiritual contemplation of and concentration on his physical appearance in the mirror, the Noh actor who wears a mask is possessed by the character he is to play through the medium of the mask he wears.

Though centuries have passed since Noh first became an art form and even more time has passed since it first began to develop as a ritual, according to scholar Solrun Hoaas the attitude toward the mask in Japanese performance and thought retains that the mask is “an embodiment of a ‘wholly other’” who can move and act through its wearer. Hoaas also notes that opinions about the Noh mask throughout history have shifted “from functioning as a receptacle of the god to a central focus for the controlled expression of emotion,” but that “in Noh theatre today…the legacy of possession is a dominating dramatic concept and the mask is seen as an agent of that possession.” The uses and qualities of the Noh mask as a method of subtle yet profound emotional expression are also retained, but the predominant function of the mask is to allow the actor to be possessed by the spirit of the mask for a performance.

As with the masks in Noh theatre, so with masks in Majora’s Mask. The transformative masks enable the spirits of those masks to possess Link and to empower him to navigate their homelands and complete the acts of valor and heroism that they would be unable to complete otherwise (because of the unfortunate condition of being dead). But what of the other masks in the game? They do not transform Link’s shape, at least not as dramatically as the transformative masks. However, though Link may not change in appearance aside from the donning of a new accessory, wearing the non-transformative masks and speaking to various non-player characters yields changes in dialogue. One of the translators of the game, Jason Leung, has commented on this in his development journal: “Link can talk to every character, and they’ll each say something different depending on the situation…I had to write dozens of replies for each character based on the time of day and the mask Link’s wearing.” Thus, Link is addressed differently by different characters depending on the mask he wears.

What is especially striking about this is that some characters will address Link as though he is someone else, as though they do not recognize that he is merely wearing a mask. For example, when wearing Don Gero’s Mask, Link is able to talk to variously colored frogs throughout Termina each of whom address Link as though he is Don Gero, “conductor of the frog choir.” None of the frogs seem to realize that they are merely addressing a mask.

It may be argued that the frogs are merely animals and therefore not as intelligent as, say, another human being. However, something similar occurs in Ikana canyon when wearing various masks representative of its deceased denizens. In the Ikana graveyard, there is a small unit of dead soldiers in the form of a type of creature called a Stalchild. The gravekeeper explicitly states that “all the graves here belong to the family members of the King of Ikana Castle” who are a type of creature called a Stalfos. The appearance of these creatures strongly implies that they are at least humanoid and are capable of human thought, speech, and movement. For all intents and purposes, a Stalfos and a S

It may be argued that the frogs are merely animals and therefore not as intelligent as, say, another human being. However, something similar occurs in Ikana canyon when wearing various masks representative of its deceased denizens. In the Ikana graveyard, there is a small unit of dead soldiers in the form of a type of creature called a Stalchild. The gravekeeper explicitly states that “all the graves here belong to the family members of the King of Ikana Castle” who are a type of creature called a Stalfos. The appearance of these creatures strongly implies that they are at least humanoid and are capable of human thought, speech, and movement. For all intents and purposes, a Stalfos and a S

talchild are the skeletons of dead humans/dead Hylians. Thus it is odd that, when Link wears the Captain’s Hat, the Stalchildren in the graveyard address him as though he is Captain Keeta, a giant Stalchild who gives Link the Captain’s Hat once Link defeats him in a fight. The Stalchildren salute Link, stand at attention, call him “Captain,” and take orders from him even though Link is, as the description of the Captain’s Hat implies, merely posing as Captain Keeta.

Various other masks like Romani’s Mask and Kafei’s Mask do not yield such odd responses and mistakes about Link’s identity from non-player characters, but they do grant Link (and the player) access to areas where Link has never been before and where he is a stranger, usually without any questioning of his identity or his associations by non-player characters. Very rarely will a non-player character mention seeing through Link’s disguise as is the case with the fox-spirit (kitsune) when wearing the Keaton Mask.

In some situations, the masks even have magical qualities such as the Stone Mask’s ability to make its wearer effectively invisible by becoming “plain as stone” or the Bremen Mask’s “strange power of making young animals mature.” Thus, the dialogue and text of the game implies a type of transformation which is not as obvious as that shown to the player when Link wears one of the transformative masks. The magical qualities of certain masks emphasizes this idea as they enable Link to do things that he could not do otherwise (e.g. sniff out truffles using the Mask of Scents).

Ishii describes the phenomenon of possession of the actor by the spirit of a mask as an “almost magical interaction” between the actor, the mask, and the mirror in the mirror room. This offers an adequate explanation of the non-transformative masks in Majora’s Mask. Something magical and inexplicable occurs when Link wears certain masks and does certain things or talks with certain people. He still seems to be possessed by the spirit of whatever mask he wears, but it is not as dramatic or explicit as it is with the transformative masks. The player can still see Link when he wears a non-transformative mask and can tell that they are still playing as Link and not as Link-plus-another-character. Certain other characters in the game, though, recognize Link as someone who is not himself, even if the person as whom they recognize him to be is as familiar to them as a commander with decades-old authority or a renowned musical leader.

So, to recap:

- The masks in Majora’s Mask suggest a possession of Link by the spirits contained within the masks he wears, especially when it comes to the transformative masks

- The concept of possession by a character via a mask is Japanese in origin and derives from ideas and traditions in Noh theatre; keep in mind that in Western thought, an actor assumes a character while in Japanese thought the actor is assumed by a character (especially via a mask)

- The non-transformative masks, though they’re not as dramatic as the transformative masks, still result in Link being recognized as another person and, in that sense, do transform him (though in a way that is more textual than visual)

These concepts are foundational to understanding Majora’s Mask in its cultural context and, ultimately, to understanding its meaning.

Source: Solrun Hoaas’ “Noh Masks: The Legacy of Possession,” Mikiko Ishii “The Noh Theater—Mirror, Mask, and Madness”