Link: Theories on the Protagonist and Emergent Narrative

Posted on December 14 2012 by Legacy Staff

We’ve previously discussed Robert McKee’s theories of the archplot, miniplot, and antiplot, and how they apply to the Zelda series. Today, we’re going to continue delving into McKee’s theories with a discussion of our perennial protagonist, Link. He’s been the player character in every canon Zelda game to date, and though we’ve seen many incarnations of him throughout the years, he’s still been the same character at his core.

We’ve previously discussed Robert McKee’s theories of the archplot, miniplot, and antiplot, and how they apply to the Zelda series. Today, we’re going to continue delving into McKee’s theories with a discussion of our perennial protagonist, Link. He’s been the player character in every canon Zelda game to date, and though we’ve seen many incarnations of him throughout the years, he’s still been the same character at his core.

McKee’s theories of the protagonist are, at their base, about desire. He sums up the foundation of a good protagonist with five statements.

1. The protagonist has a conscious desire.

This is fairly simple: Every protagonist is going to want something, is fully aware that they want that something, and shows that they want that something through their actions. This desire can be a physical object or action — for example, the police chief in Jaws desires the destruction of the shark — or it can be an internal, abstract desire, such as the desire for maturity of the main character in Big. The protagonist’s actions are going to quite explicitly exhibit this desire.

2. The protagonist has the capacities to pursue the object of desire convincingly.

This is a bit less obvious, but it makes sense: The protagonist must be characterized in such a way that the audience believes them capable of pursuing their desire. For example, a character with a desire to walk on the moon must be, if not an astronaut already, an engineer or a scientist working in that field. A mild-mannered office worker in a small town in New England could not convincingly pursue the desire to walk on the moon. The character’s personality and traits must work in the service of pursuing the object of desire (the thing they want), otherwise the audience will be less willing to believe the story.

In some cases, the protagonist may not be in possession of skills or abilities that directly contribute to their ability to convincingly pursue their desire. In these cases, a tremendous amount of will or determination will suffice; the audience will respond well to characters with hope. But it’s a fine balance, as a protagonist with no skills that directly contribute to their pursuit of desire runs the risk of being unable to attain their desire at all. Which brings us to…

3. The protagonist must have at least a chance to attain his desire.

An audience has no interest in the story of a character trying to reach a desire they have no chance of reaching. If our astronaut that wants to walk on the moon is working for a company that has no plans to run manned missions, the audience won’t want to hear this story. There must be a chance — however miniscule — that the protagonist can reach the desire. Hope is an incredibly strong emotion, and audiences will quickly latch onto hope. Hopelessness, on the other hand, is alienating, and will detach the audience from the story.

An audience has no interest in the story of a character trying to reach a desire they have no chance of reaching. If our astronaut that wants to walk on the moon is working for a company that has no plans to run manned missions, the audience won’t want to hear this story. There must be a chance — however miniscule — that the protagonist can reach the desire. Hope is an incredibly strong emotion, and audiences will quickly latch onto hope. Hopelessness, on the other hand, is alienating, and will detach the audience from the story.

Likewise, while a character with no directly applicable skills may be able to convincingly pursue his desire, if that lack of skill makes him completely unable to attain his desire, then the audience will reject him on the grounds of hopelessness. Will and determination only work if the character has a chance even without directly useful skills.

4. The protagonist has the will and the capacity to pursue his object of desire to the end of the line, to the human limit established by the setting and the genre.

This is a very wordy way of saying that the protagonist will stop at nothing to reach his goal, and will be able to pursue it all the way until he has reached the very limit of human ability. As I said previously, hopelessness is alienating; a protagonist who gives up will send the audience running for the hills. A protagonist who continues to try against impossible odds? Audiences love it. Our astronaut isn’t going to stop trying, no matter how many times a mission fails to make landfall.

5. Conflict arises from the gap that exists between the protagonist’s expectations and the actual result of his actions.

This is the key statement, as it is the “mechanism of conflict”: The protagonist is going to take actions to attain his desire. When the results of his actions are more extreme than his expectations were, the gap between expectation and result creates conflict. Our astronaut and his team are set to fly a mission to the moon, but a technical problem results in them overshooting their landing zone and having to circle back around the moon, carefully monitoring all of their instruments to ensure their survival. They expected to land on the moon, but their action had more extreme consequences than they foresaw, and thus the conflict arose. The gap between the two gives rise to this conflict, which then fuels the rest of the story. There can be — and are, in most cases — multiple gaps of this nature within the course of a story.

These statements of KcKee’s form a very basic picture of the protagonist as a character with a strong force of will who will stop at nothing to achieve the object of his desire, and create conflict through the actions he takes to do so.

This is a model that can be applied to almost every protagonist in any medium, but applying the model to Link is a rather interesting case. Though Link is almost universally considered a good protagonist (and rightfully so), there are two clear problems with applying the model to Link. Let’s examine these problems, and determine why Link is considered a good protagonist despite them.

The Problem of Link’s Desire

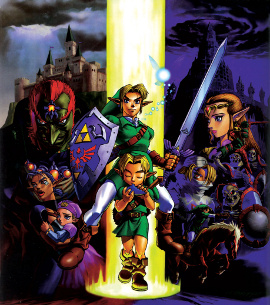

We’re going to look at Ocarina of Time as an example, since I’d call its story the typical Zelda story. What is Link’s desire during the game? What exactly does he want to accomplish? Does he want to fulfill his destiny and become the legendary Hero of Time? Does he want to carry out the Deku Tree’s dying wish out of loyalty to the guardian spirit? Does he want to fulfill Zelda’s wish and end Ganondorf’s tyrannical influence? Does he simply want to return to an idyllic life of peace and calm? Does he want to explore Hyrule, regardless of the situation that compels him to do so?

We’re going to look at Ocarina of Time as an example, since I’d call its story the typical Zelda story. What is Link’s desire during the game? What exactly does he want to accomplish? Does he want to fulfill his destiny and become the legendary Hero of Time? Does he want to carry out the Deku Tree’s dying wish out of loyalty to the guardian spirit? Does he want to fulfill Zelda’s wish and end Ganondorf’s tyrannical influence? Does he simply want to return to an idyllic life of peace and calm? Does he want to explore Hyrule, regardless of the situation that compels him to do so?

The answer is none of these… and all of these. In fact, Link himself has no desire. It has been said throughout the series’ life that Link is so named because he is intended as a “link” to the player, a way for the player to connect on a deeper level with the game. Because of this intention, in most every case, Link is not branded with a particular identity or character; he is very much a blank slate. Link has no inherent desire, which defies the portrait of the protagonist that we just defined. So why, then, is Link such an effective protagonist?

Quite simply, he is an effective protagonist because he allows you, the player, to inject him with your own personality and your own desires. And because each player will play the game differently and with different desires, Link is an incredibly versatile protagonist, able to play out any number of narratives simply through the way people choose to play the game. He is the perfect protagonist for a storytelling device known as “emergent narrative”: a story that arises out of the way players interact with the game world.

For example, let’s say that we have three players all playing Ocarina of Time. These players have all drawn the Master Sword and acquired the Hookshot from Dampe’s Tomb in the Graveyard, and are turned completely loose into the world. Player A decides to proceed straight to the Forest Temple. Player B decides to instead rescue Epona from Lon Lon Ranch. Player C opts to simply roam the world, exploring Hyrule Field and surveying the changes that Ganondorf’s reign has brought to the region. Now think about the different desires and stories at play here. Player A is motivated by a desire to finish the game, or to end Ganondorf’s reign, and thus his story displays a sense of immediacy and urgency. Player B is motivated more by personal desires, such as the desire to rescue the horse that he befriended as a child, and thus his story is less urgent. Player C wants to go sightseeing, and his story is the least urgent and completely ignores the main story of the game in favor of just exploring the new landscape.

These are all different stories that can emerge from the game, all because Link’s blank slate nature enables players to inject their own desires into him. What enables these different emergent narratives to take shape is the presence of abnegation. Abnegation is a term that refers to the ability of a player to ignore the main story or object of the game and instead focus on smaller, side efforts. Sidequests are an obvious and ubiquitous source of abnegation, but the very presence of an open world that can be explored, with things like hidden holes and concealed treasure chests, offers abnegation as well. Allowing a player to both instill their own desires in the game’s character by not developing the character as an individual, and to ignore the main story set before them, provides numerous opportunities for an emergent narrative to take shape.

If we turn to other games in the series, this same format appears numerous times. In Majora’s Mask, the game turns the player loose very early on, allowing them to either proceed onward to Woodfall, pursuing the desire to fulfill the promise to Tael by summoning the “four who are there”, or to explore Clock Town and interact with its many citizens, pursuing the desire to better understand Termina. In The Wind Waker, players are free to explore the sea during much of the game, fulfilling the desire to explore, or they can proceed with the main story, work toward stopping Ganon’s plans, and fulfill the desire to rescue Aryll and, later, Tetra. The Zelda series provides so many avenues for the player to pursue their desires, and in so doing gives rise to a near endless number of emergent narratives. Replaying the games can often feel like an entirely different experience if you allow yourself to consider different avenues at different times, creating new narratives in the process.

If we turn to other games in the series, this same format appears numerous times. In Majora’s Mask, the game turns the player loose very early on, allowing them to either proceed onward to Woodfall, pursuing the desire to fulfill the promise to Tael by summoning the “four who are there”, or to explore Clock Town and interact with its many citizens, pursuing the desire to better understand Termina. In The Wind Waker, players are free to explore the sea during much of the game, fulfilling the desire to explore, or they can proceed with the main story, work toward stopping Ganon’s plans, and fulfill the desire to rescue Aryll and, later, Tetra. The Zelda series provides so many avenues for the player to pursue their desires, and in so doing gives rise to a near endless number of emergent narratives. Replaying the games can often feel like an entirely different experience if you allow yourself to consider different avenues at different times, creating new narratives in the process.

The Problem of Link’s Expectations

The gap, or the mechanism of conflict, is created by the difference between the protagonist’s expectations of his action and the actual result of the action. As we have established, Link is, for the most part, a blank slate; he may show emotions from time to time, but he has no clearly expressed desires and no clearly conveyed expectations. So from what expectations does the gap form?

As with the problem of desire, the answer is quite simple: Your expectations. Rather than create conflict through Link’s expectations as he pursues his desire, the series creates conflict through your own expectations as you perform actions to pursue your desire. You directly control Link; your actions and your expectations of them are what create the conflict.

Let’s go back to Ocarina of Time. The largest gap occurs when Link draws the Master Sword from the Pedestal of Time, allowing Ganondorf access to the Sacred Realm. As we’ve said, Link as a character had no expressed expectations. But you, the player, did. You thought that drawing that sword was going to prevent Ganondorf from reaching the Triforce, but it had the exact opposite effect. The gap is created because your expectations of the result of your action did not align with the real results.

It’s a rather elegant solution, because it involves the player in the game’s plot more than it would if it used Link’s expectations. Because you expected a certain outcome, rather than being told that Link expected it, your actions are given more weight than they would have if you performed those actions because Link thought they were the right thing to do. Instead you thought they were right, and that difference is critical to involving the player in the story. In this situation you are an actor in the story rather than a detached observer who is operating the character like a puppet, and that elicits far stronger emotional reactions.

It’s a rather elegant solution, because it involves the player in the game’s plot more than it would if it used Link’s expectations. Because you expected a certain outcome, rather than being told that Link expected it, your actions are given more weight than they would have if you performed those actions because Link thought they were the right thing to do. Instead you thought they were right, and that difference is critical to involving the player in the story. In this situation you are an actor in the story rather than a detached observer who is operating the character like a puppet, and that elicits far stronger emotional reactions.

There’s a question here that needs to be asked, however. You had these expectations when pulling the sword from the pedestal, but why did you have these expectations? What led you to expect that pulling the sword from the pedestal would stop Ganondorf from obtaining the Triforce? The answer is that Nintendo told you, subtly. In addition to having characters throughout the game (Zelda, the Deku Tree) imply that getting the Spiritual Stones was of the utmost importance, there’s a moment right before you draw the sword that preys upon previous understanding of the Master Sword. The sudden musical silence and Navi’s reaction to the sword place a great deal of importance on the blade, and for those who had played A Link to the Past, the sword’s status as the Blade of Evil’s Bane only further amplified those expectations. Everything in the game had been set up to instill these expectations in you, the player, so that Link, the character, would have these expectations. It’s an intricate bit of sleight of hand, but it’s powerful. Rather than having Link directly express his expectations, Nintendo opted to have other characters (and even knowledge of past games) create these expectations within the player, only to contrast them with reality and pull the player into the story while also creating the gap critical to the conflict of the rest of the game.

Conclusions and a Challenge

Link is an interesting protagonist precisely because he does not fit the model. He is effective because he forces the player to take on the role of protagonist, with the desires and expectations that give rise to conflict coming directly from you rather than being conveyed to you. It’s an involving act that makes what are, at their core, very simplistic stories that don’t even approach deep character study feel like some of the most exciting stories in the medium. Is the story of Ocarina of Time as complex or multi-layered as, say, any of the Metal Gear Solid titles? Not at all, but because you’re forced to become the protagonist of your own story, if feels just as engaging.

In closing, I’d like to present you, constant reader, with a challenge. The next time you replay a Zelda game, consider throughout your playing: What is your desire? What do you want out of the game at any given moment, and are you actively pursuing that desire? How are your expectations being manipulated in preparation for the mechanism of conflict? Think on these things as you play. If you aren’t actively pursuing your desire at a given point, and the game has freed you to do so, then go pursue your desire! I guarantee you that you will find a new emergent narrative in your playing, and the experience will feel refreshingly novel. Because when you’re the protagonist of your own story, it’s best to let yourself pursue your own desires.

Try it sometime, and you’ll be sure to gain a new appreciation for the series’ storytelling.