Link in Wonderland: An Analytical Comparison Between Majora’s Mask and Alice in Wonderland

Posted on March 15 2013 by Dathen Boccabella

People often compare The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and its sequel, Through the Looking Glass, which inspired a 1985 two part television film entitled Alice in Wonderland. This television version of the classic tale bears more similarities to Majora’s Mask than any other version of the story, and so serves as the basis for this article. But, when this tale is analyzed with a critical eye, do its similarities with Majora’s Mask actually go deeper than the rabbit hole?

Alice in Wonderland is often referred to as a nonsense tale.

A simple fantasy story with no real meaning, purpose or lesson; often

criticized for lacking a definitive storyline, which is not entirely

different from some people’s views on Majora’s Mask. But, as the Dutchess from Alice in Wonderland says, “Everything has a moral, if you find it.” Despite what critics have claimed, there is much that can be drawn from this classic story, as there is much to learn from Majora’s Mask. The story’s predominant theme is one of identifying yourself and growing up: a theme that is clearly present in Majora’s Mask, and was explored in Hylian Dan’s popular article, The Immortal Childhood.

Alice in Wonderland begins at the home of the titular

character Alice, a seven year old girl. Despite her age, Alice is

adamant that she is grown up, and asks her sister to “stop talking to me as though I was a child”.

Alice is the youngest in her family and because of this her mother

won’t allow her to join the grown ups for tea. Instead, Alice is sent

outside to amuse herself, where she begins to follow an unusual white

rabbit. The rabbit leads her into its rabbit hole, which turns out to be

a portal that leads Alice into Wonderland, a childish world with the

theme of a deck of cards.

In Wonderland, Alice journeys far, meeting many different characters.

Many of them are really quite immature, immersing themselves in

childish habits; whether they’re rolling around the ground hysterically,

breaking dishes by throwing them at people, ridiculously overusing

pepper in cooking, or ordering beheadings to solve every little

annoyance. Even though she is homesick, and worried that she will never

see her family again, Alice must be the mature person in this world of

immaturity.

Throughout her journey, Alice has to run errands and is ordered

around more so than she has ever been in her life. She also struggles

with her own identity, as during her quest she is often growing and

shrinking in size, from unusually little to abnormally large. Due to her

constant form changing, Alice says “I hardly know” who I am, “I knew who I was when I got up this morning.” She states that “being so many sizes in one day is very confusing”

and that she is not herself. Along her quest, Alice comes to terms with

what it truly is to be grown up. A wise cat helps her to this

realization, as he informs Alice that there’s no going back once you’re

grown up. He tells her that becoming an adult is a life of

responsibility and stress, without endless time to play.

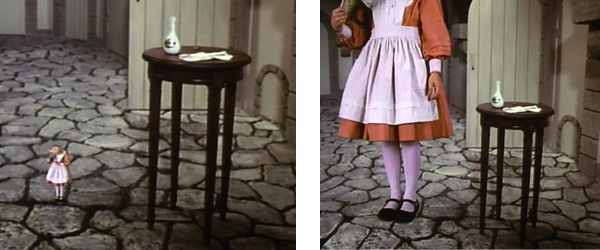

Alice changes in size throughout her quest.

Eventually Alice awakens, learning that her adventures were some kind

of dream. She returns to her house, but learns that she isn’t quite

home. Alice finds herself in Looking Glass Land, a world on the other

side of the mirror, this time based on the game of chess. In this new

land, Alice reads a poem about a foul beast, the Jabberwocky. She learns

that this beast is threatening the land, but also that it is her

creation: a physical manifestation of her childish fears. Interestingly,

it is a wise owl that guides Alice on the path she must take, telling

her that she “will never grow up”, not until she can “conquer the fears inside”, otherwise she “will never be more than a child.”

In this chess themed land, Alice begins as a simple white pawn in the

second square, where she must progress to the eighth square, the place

where pawns become queens. Alice had to grow from having a childish

mind, to possessing a queenly mind. She began the story being bossed

around, but ends it in a position of ruling power. At the film’s climax,

Alice overcomes her fears by telling the Jabberwocky that she doesn’t

believe in him. As he is destroyed, Alice again wakes up, but this time

she is safely home, resting in her armchair. Her mother had been calling

her, to give her some good news. To Alice’s delight, her mother says “I think you’re finally quite grown up enough to join us” for tea. The film happily concludes with Alice now having mentally matured enough to be included by the adults.

This moral bears a striking resemblance to the story of Majora’s Mask.

Link is a 10 year old boy who inside himself believes that he is an

adult. Having been the Hero of Time, and having gone through his epic

journey in Ocarina of Time, to end up back in his childish form

with all of his past memories, we can only imagine would be quite a

disturbance to him mentally. It took until the very end of Link’s

adulthood journey for him to really come to terms with the adult world,

and for him to realize his immature actions, as in his relationship with

Princess Ruto. During his quest he manipulated his stature from adult

to child numerous times, and to now find himself trapped as a child

until he literally grows up is a challenge. Link feels independent and

can’t return to the way things used to be in Kokiri Forest. He has to

move on, just like children eventually move away from their parents. He

truly thinks that he is an adult.

Being on unstable terms of who he really is, Link finds himself

thrown into Termina, a land dominated by the childish theme of masks.

Link is quite obviously annoyed by being treated as a child. Whether

it’s the Clock Town guards telling Link that they “cannot allow a child”

to pass, or one of the many other people referring to link as just a

kid, this was clearly frustrating for Link. He began his quest in the

form of a Deku Scrub, a being even younger than him at 10 years. Not

only did Link feel like an adult stuck in a child’s body, but he really

struggled to identify who he is: an adult, a child, or a deku scrub?

As he progresses throughout Termina, Link continues to change his

form, and is challenged by this. Eventually he ends up being adult half

the time and child the other half. In Goron and Zora form he is an

adult. As the Deku Scrub and himself he is a child. He is entirely

conflicted, feeling truly split between the child and adult worlds. As

Mikau he learns the responsibilities of the adult life, as Alice was

taught by the cat. Similarly to Alice, Link changes forms and struggles

to know who he really is, but he must very quickly become the mature

person in Termina, as its citizens break down and despair at the

approaching end of the world.

Link runs many errands along his quest, and as he continues to play

the song of time and relive the three day period, he comes to have a

more mature, a more grown up view of the world. Majora’s Mask

is a quest where Link has to come to terms with the adult side of him.

The wise owl, Kaepora Gaebora, helps Link along the way, encouraging him

to live up to his destiny of defeating Majora, who threatens the land.

He must defeat Majora, not only to save the world, but also for himself,

because Majora represents the fears that he holds inside of himself.

Regardless of how Majora came into being, the demon is

eternally childish. Despite existing for ages, it has the psyche of a

child, and prays upon the Skull Kid who is bound to eternally remain

a child. The childish mind is the exact thing that Link fears: being

stuck as a child, when he feels like an adult. He feels that defeating

Majora will be like overcoming the childish portion of himself. To Link

in his normal form, Majora is extremely powerful, and is even more so to

the childish Deku Scrub. What better way is there for Link to defeat

Majora, than by earning and donning the Fierce Deity mask? With this

Link is now an adult. In his adult form, Link

can easily triumph over Majora, who is now nothing but a weak child. It

was Link’s fears that truly gave Majora its intimidating power.

Link dons the Fierce Deity Mask, giving him the power to easily defeat Majora.

The child wearing Majora’s Mask on the moon is the same child that

gives Link the Fierce Deity Mask. The Fierce Deity represents the adult

side of Majora. Being such a childish and playful mind, Majora wants to

get rid of anything remotely adult. Majora believes in the childish mind

over the adult, and has no problem giving Link its adult self. Majora

doesn’t realize how gladly Link receives this, and does not know

that she is giving Link the exact thing the hero needed. Because Majora

sees adults as evil, it states that Link is the “bad guy. And when you’re bad, you just run.”

Majora hates adults because they won’t play, they won’t share its

mindframe, just like the Skull Kid feuds with the Giants

because they refused to play with him. As the Fierce Deity, his true

adult self, Link is able to easily defeat Majora, his childish fear. As

was the case with Alice, Majora’s Mask concludes with Link as the adult that he believed himself to be right from the start.

Alice, despite being told by her sister that she “can’t really think that she’s a grown up”,

still manages to quickly mature. Link, despite being a child outwardly

and in everybody else’s mind, is able to reveal himself as the adult he

truly is. They may have believed they were already grown up, but they

still had more to learn and more to see of the world. Growing up isn’t

something that will just suddenly occur, it is a journey: a journey that

is never about size, but about your mindframe. Only by facing their

fears could Link and Alice grow up. Alice had to directly speak to the

Jabberwocky, and Link trusted in the Fierce Deity mask, even though

Majora gave it to him. Cremia, from Majora’s Mask says that “by doing one good deed, a child becomes an adult”.

Link accomplishes many righteous acts, from saving the land, to

reuniting a struggling couple, amongst much more. Alice also saves the

land, helps a trapped goat, rescues an abused baby and vouches for a

prisoner to have a fair trial. If being an adult only requires one good

deed, then both Link and Alice qualify by the end of their quest.

Another more common moral, which is dominant in both Alice in Wonderland and Majora’s Mask,

is the idea of appreciation and there being no place like home. Once

Alice is in Wonderland, she finds herself separated from those she

loves: her mother, father, cat and sister. She especially worries that

her “poor mother must be in a terrible state.” Alice only

begins to truly appreciate her mother once they have been separated.

Only once she is gone does Alice notice what it is like to be without

her. She misses her mother and is certain that her mother has begun to

miss her.

In Majora’s Mask, Link goes on his quest, completely abandoning his friend Zelda. Link focuses on finding Navi,

a friend that is lost, instead of appreciating those friends that he

does have. Once consumed in the affairs of Termina, Link comes to

realize that he shouldn’t waste his time searching for Navi, but should

return to Zelda. He came to realize how much he appreciated her, once

she was gone. At the conclusion of Majora’s Mask, the Happy

Mask Salesman tells Link that they have both gotten what they were

after, and although it seems like Link has gained little, he has gained

this concept of appreciation. He has learned to stop searching for what

is lost, to move on and return to Zelda. The Mask Salesman goes on to

say that a parting need not last forever, reminding Link that Zelda was

longing for the day when they would meet again.

Both Link and Alice learned to appreciate those who they had left

behind and, as their quests progressed, they wished for nothing more

than to be home, able to tell those they love how they feel. Alice is

always afraid that she will never find her way home again, and any

chance of doing similar looked fairly bleak for Link during his

adventure. Link sympathizes with those he meets that are separated from

their loved ones and helps them to find their way back home. Whether

it’s freeing the monkey imprisoned by the Deku King, restoring Pamela’s

father from his gidbo possession or by reuniting Kafei with Anju, Link

helps many find their way home.

As Link watches Anju say “welcome home” to Kafei, he longs

for Zelda to say the same to him. Similarly, Alice also helps others to

find their way back home. There’s the goat that she releases from

entanglement, and the prisoner who she longs to help. When vouching for

the prisoner, Alice nicely sums up this theme for both Link and herself

when she says, “set the prisoner free and let him go home. His

family probably misses him very much. And one of the worst feelings in

the whole world is to be homesick. I ought to know.”

Link remembers his parting with Zelda and Alice with her mother.

Without a doubt, themes form the most dominant similarities between

these two tales, but they aren’t what you usually hear about when

someone says that the two tales are similar. Usually, it is the rabbit

hole, the portal to Wonderland, which is mentioned. Alice begins her

journey by chasing a white rabbit through the woods, where it runs into a

pitch black hole in a hillside. Alice follows, and being unable to see

her way in the dank hole, she stumbles over the edge and falls into the

rabbit hole, a mystical, time distorted portal of sorts. She lands on a

patch of soft shrubbery and continues to follow the rabbit through some

underground caverns, eventually coming to a mysterious door. The door

leads to a room full of other doors leading to various places, and from

there Alice makes her way into Wonderland, a very strange land indeed,

and while it appears lush, it is far from a paradise.

As for Link, instead of following a rabbit, he chases the Skull Kid

through the Lost Woods to regain his stolen ocarina and horse. As Alice

did, he follows blindly into a dark cave where he too stumbles into a

dark abyss. Falling mysteriously through masks, instruments, symbols and

clocks, Link lands safely on a Deku Flower. After being cursed to live

as a Deku Scrub by the Skull Kid, Link continues the chase through more

caverns and into an endless expanse. Only being able to reach one

corridor, Link makes for it, where he travels through a mysterious door

into the Clock Tower of Termina: a far from joyous place. For the time

being, both he and Alice were outrun by those they were pursuing

We can’t be entirely sure of the nature of these portals, and it is

possible that the room of doors and the large cavern are actually

in-between the worlds. Perhaps for one to form a strong opinion on the

nature of the portals, they need to have a strong grasp of the nature or

reality of the adventures. Termina is firmly established to fans as a

parallel land, and the quest of Majora’s Mask as a truly physical quest; but it is not without dreamlike qualities. The story of Alice in Wonderland

is portrayed entirely as a dream, which was the novel’s original

intention. The movie does conclude in a way that makes the whole quest

appear as slightly more real than a dream, but her clear awakening shows

that its make up is fundamentally dreamlike. The land itself bears no

parallel qualities to Alice’s homeland, unlike the direct resemblance

Termina is of Hyrule. Link is knocked unconscious at the beginning of

his journey, and this, bundled with the ethereal quality of Termina,

could be seen as dreamlike. But Link is quite truly awake, and his

journey is much more real than Alice’s.

The ‘Rabbit Holes’.

One notable similarity between the nature of the two quests is their

relative time flow. Alice’s dream, in reality, seems like hours, even

days, but she is lucky to be asleep for any more than an hour. Her dream

passes in a quicker time so that she can come to appreciate her family,

and mature, in quite a small timeframe. Similarly, the timeflow of

Termina appears to be much faster than that of Hyrule, as indicated by

the interactions of the Skull Kid with the land. Thus, Link is also able

to mature and come to appreciate Zelda in a smaller timeframe.

There are strong similarities that can be drawn between the 1985 television film Alice in Wonderland and Majora’s Mask.

Chiefly it is in regards to morals, with some more prominent aspects

like another world and portals also bearing a resemblance. Really, the

key point to note is the versions. Alice in Wonderland is so

popular that there have been many rewrites, stage productions and films

that are all based upon the writer’s interpretations of the original

novels. Not every version bears such a striking resemblance to Majora’s Mask,

in fact, in some versions the rabbit hole and parallel world concepts

are the only similarities to be found. While this particular film

version is quite similar, it seems that Alice in Wonderland’s

similarities to Majora’s Mask are due to reputation, more so

than to reality. Do the similarities go deeper than the rabbit hole? In

this instance they do, but in many other versions, including Carroll’s

original novels and the most recent 2010 film adaption, the rabbit hole is often where the foremost

similarities stop.