Linearity in Skyward Sword

Posted on July 12 2015 by Mark Olson

Skyward Sword has been the recipient of a variety of complaints from a variety of sources regarding a variety of the game’s elements. A hot topic nowadays is its linearity. In this article, I take a look at linearity in the entirety of the Zelda franchise, with a focus on how it applies to Skyward Sword.

Skyward Sword has been the recipient of a variety of complaints from a variety of sources regarding a variety of the game’s elements. A hot topic nowadays is its linearity. In this article, I take a look at linearity in the entirety of the Zelda franchise, with a focus on how it applies to Skyward Sword.

When it comes to critiques of Skyward Sword on the internet, one word gets thrown around a lot: linear. Now, whether linearity is in and of itself a good or bad thing is a debate for another time; instead, I would like to look at what linearity truly is and how it’s been implemented in the context of Zelda games.

Linearity can be divided into a number of categories depending on who you ask. The first I’ll be touching on here is a linear story. For an average gamer, these won’t be hard to come by; linear stories are far more commonplace than their alternative. I’ll take Phantom Hourglass as an example, though you could easily substitute nearly any Zelda game in its place. The game opens as Tetra is given the Medusa treatment and Link washes ashore on an unknown island. After exposition, exposition, and more exposition the player heads to The Temple of the Ocean King to learn the whereabouts of the spirits of Wisdom and Power. After that, Oshus kindly informs Link that he must acquire some rocks to make a sword. You get the point. One plot point to the next in a determined order. It directly follows a time-line with no lee-way. Even A Link to the Past, a game myself and many others have praised for the choices afforded to players in regards to dungeon order, has a strictly linear story.

Clearly, then, Skyward Sword’s story running on rails is hardly the problem. If it were, the Twilight Princess hate so prevalent a couple of years ago would still be burning strong. This brings us to another kind of linearity: progression.

Though it is closely tied to story, there is a distinction between linearity of progression and linearity of story.

Let’s take a look at a game I briefly mentioned before, A Link to the Past. Even though it exhibits linearity of story, A Link to the Past does not have a linear progression path, at least not in the second act of the game. After completing the Dark Palace, players have a variety of options as to where to go next. If they want to get the Fire Rod early, they can go ahead and do so. If they feel like getting some ore to power up their sword before heading in to the hellish Skull Woods (which I highly recommend), they can do that, too. The progression of the player is, for the most part, non-linear. Obviously, Link can’t just skip the seven maidens and head right in to Ganon’s Tower, but there are a range of potential orders for the player to tackle dungeons in.

Now, let’s put this in the context of Skyward Sword. There should be one glaring issue with this statement; you can’t. The player has next-to-no options as far the order of dungeons or items goes. Initially, this may seem like the linearity that there are so many complaints about. However, the same “complaint” could be said about almost every other game in The Legend of Zelda franchise. Twilight Princess, the game from which Skyward Sword deflected a lot of hate, is strictly linear in the progression department. The current fan-favorite of the series, Majora’s Mask, has a strictly determined order through which the player moves through the game. Though some may argue otherwise due to the game’s abundance of side quests that can be completed at many points throughout the playthrough, this is simply not the case. You see, these events don’t need to be completed at all. Though fun and rewarding, checking an optional task off of your Bomber’s Notebook does not ferry the player through the plot. As such, Majora’s Mask and the majority of Zelda games progresses linearly.

This brings us to the final type of linearity (at least the last one relevant here): linear level design. To be clear, I’m not referring to the dungeons here; the dungeons were as open in Skyward Sword as in any Zelda game. Instead, I’m talking about the over world, or… The second over world? The slightly-less-over world? Honestly, I don’t know with this game.

All joking aside, the land beneath the clouds in Skyward Sword was incredibly linear, particularly Eldin’s Volcano. Though not as extreme as the following example, the issues people took with Skyward Sword in this regard are comparable to those taken with Final Fantasy XIII. Instead of an over world that allows players to roam freely, Skyward Sword presents a series of bottlenecks for the player to find their way through.

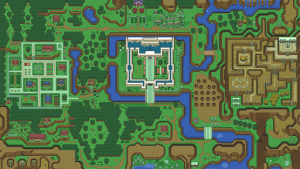

This is an issue that is unique to Skyward Sword (although Spirit Tracks had a similar problem, it stemmed from an entirely different reason). For comparison’s sake, let’s take a look at the maps of a region from Skyward Sword and the over world from A Link to the Past.

Pretty different, huh? The in-congruencies should be obvious; though similar in scope, one allows for players to take a variety of equally viable paths to their objective. In the other, there’s generally a right way and a wrong way to do things. This goes against the spirit of exploration; instead of finding things out on their own, players are immediately shown by the lack of a wall or lava pool where to go. Don’t get me wrong; A Link to the Past isn’t the most open-ended game ever, but in that game your movement was constricted by the items you had, NOT the layout of the environments.

Finally, I have gotten around to the main complaint levied against Skyward Sword. This article was, contrary to the general tone of the last couple of paragraphs, not intended to hate on the game. As a matter of fact, I am actually quite fond of Skyward Sword; it’s not even my least favorite of the 3D games. My hope in writing this was to act as a bit of a translator between the two armies in The Battle of Skyward Sword, at least on the front of linearity.

Agree or disagree, sound off in the comments below.