Incorporating RPG Elements into Zelda Games

Posted on May 10 2013 by Hanyou

Zelda games could use some RPG elements. Some might argue that Zelda games already have RPG elements; Skyward Sword showcased an increased focus on character customization, and Zelda games have traditionally been confused for RPGs. However, in Zelda games, the focus has always been on adventure. Proper implementation of RPG elements would supplement the adventure elements and wouldn’t undermine them. Since the developers of Zelda games have traditionally been good at incorporating new elements, this change can be significant or conservative, but I have no doubt it could work. Given recent trends in gaming at large, the time may be right.

Zelda games could use some RPG elements. Some might argue that Zelda games already have RPG elements; Skyward Sword showcased an increased focus on character customization, and Zelda games have traditionally been confused for RPGs. However, in Zelda games, the focus has always been on adventure. Proper implementation of RPG elements would supplement the adventure elements and wouldn’t undermine them. Since the developers of Zelda games have traditionally been good at incorporating new elements, this change can be significant or conservative, but I have no doubt it could work. Given recent trends in gaming at large, the time may be right.

It’s probably best to define what an RPG is before delving into this topic. Opinions on what is and isn’t an RPG differ, but for the sake of this article, I’ll define it as:

a system of gameplay based on character stats.

This is incredibly vague, but that’s good; it’s vague enough to encompass everything that can be reasonably considered an RPG without including strictly adventure games. It can also explain RPG systems incorporated in non-RPG games, like Metroidvanias.

The disadvantage of this broad definition is that it could almost include sim games, RTS games, and MOBAs. That’s why it’s important that RPG gameplay is based on character stats. While this definition may still cover some games that are not RPGs, it still generally represents the drive of RPG gameplay: Building characters. It goes without saying that the “stats” are calculations; RPGs are math games.

Obviously, I speak without authority on this topic, and I can’t prove I’m right about this assessment. However, trends in the most popular RPGs should bear this perception out.

It might be time to introduce some RPG elements to Zelda.

“Why?” is the single most important question to ask before proposing anything new for Zelda games. It’s a question that could benefit all sorts of controversial discussions about the series — a game’s place in the timeline, a “darker” direction for the story, realistic/toon-shaded graphics, voice acting, etc. It’s a question that, regardless of your opinion of any single game in the series or obvious series trends, the developers often seem to ask themselves. When they change something about the world, many other elements follow suit. The developers consistently ask themselves how different aspects of their games can synergize with each other, and more importantly, why those elements coexist. Whatever you think of the trains in Spirit Tracks, for example, the world was clearly designed around them, as was the story, as were the items. It’s this sort of consistency which points toward a real conscientiousness in the development of these games. Other examples are the time element and masks in Majora’s Mask, the Dark World/Light Word mechanic in A Link to the Past, and the synergy between the graphics, story, and mechanics of The Wind Waker.

“Why?” is the single most important question to ask before proposing anything new for Zelda games. It’s a question that could benefit all sorts of controversial discussions about the series — a game’s place in the timeline, a “darker” direction for the story, realistic/toon-shaded graphics, voice acting, etc. It’s a question that, regardless of your opinion of any single game in the series or obvious series trends, the developers often seem to ask themselves. When they change something about the world, many other elements follow suit. The developers consistently ask themselves how different aspects of their games can synergize with each other, and more importantly, why those elements coexist. Whatever you think of the trains in Spirit Tracks, for example, the world was clearly designed around them, as was the story, as were the items. It’s this sort of consistency which points toward a real conscientiousness in the development of these games. Other examples are the time element and masks in Majora’s Mask, the Dark World/Light Word mechanic in A Link to the Past, and the synergy between the graphics, story, and mechanics of The Wind Waker.

The first and most obvious reason why RPG elements could benefit Zelda is that for a lot of people, Zelda games either are RPGs or are awfully close. You could say they meet some of the same criteria people expect from RPGs. It was popular a few years ago to call Zelda games RPGs. Though this doesn’t meet even the broad definition I outlined at the beginning of this article, there are some striking similarities between Zelda games and RPGs.

Zelda games are about building a character. Through collection of heart containers, upgrading equipment, etc., you perform many of the same tasks you do in an RPG. The difference is, of course, that stat-building is far more restrictive. There is almost always a single best way to build Link, and the stat boosts are incentive for exploration; he real gameplay lies in discovering the world, using keys (sometimes in the forms of items, sometimes in the form of literal keys) to proceed down a series of linear paths toward well-defined goals. The games aren’t about stat-boosting, but they still fulfill the same basic criteria.

RPGs are trendy, and it’s easy to see why. On a visceral level, they’re addictive. However, this trendiness coincides with a simplification of RPG gameplay and a marriage with other gameplay styles. The most popular RPGs are no longer just RPGs.

For an example of how simplified RPGs have become, boot up an early Ultima game or even Baldur’s Gate: You’re likely to be a bit intimidated if you’ve been weaned on the last 10 years of WRPG gameplay. Sure, Baldur’s Gate was real-time, but developer BioWare didn’t hide the fact that the combat boiled down to dice rolls. Even the comparatively recent Knights of the Old Republic series follows a similar pattern, with real-time combat that’s still unmistakably RPG combat.

Something interesting happened with the release of The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, as well as Mass Effect and a number of other early last-gen WRPGs; blatantly RPG-like combat became scorned on these shores. It didn’t matter if it was turn-based, like a number of JRPGs, or simply not action-based; combat which consistently reminded you you were playing an RPG was bad. Combat which made you think you were playing a third person shooter or a melee-based action game was good, because this was “real gameplay.”

Naturally, this extended to the stats as well. Few people would question whether or not Oblivion’s follow-up, Skyrim, is an RPG. It certainly is by the broad definition listed above, though it is also less of a numbers game than all of its predecessors. Unlike Oblivion, Morrowind, Daggerfall, and Arena, you won’t find yourself spending much time balancing numbers; instead, the game is designed so that you can smoothly graduate through different skill trees, igniting perks. There’s incentive to specialize, as better perks are located near the end of perk trees, but gone is the comparably complex system of skills bound to attributes. This downplays the RPG elements, but it doesn’t eliminate them, and the rewards you get for moving up a perk tree are very tangible. It’s not just about stat boosts; it’s about being able to feel the improvements in your character.

Whether this sort of thing is good or bad for RPGs is debatable, but it’s fantastic for tearing down the walls between the RPG and the adventure game. Coupled with the inherent character building of the Zelda series and the character customization of Skyward Sword, there are opportunities for synergy. If the developers ever felt inclined to incorporate RPG-like elements, I have no doubt that they could do a good job. They would fit the Zelda series like a glove.

Whether this sort of thing is good or bad for RPGs is debatable, but it’s fantastic for tearing down the walls between the RPG and the adventure game. Coupled with the inherent character building of the Zelda series and the character customization of Skyward Sword, there are opportunities for synergy. If the developers ever felt inclined to incorporate RPG-like elements, I have no doubt that they could do a good job. They would fit the Zelda series like a glove.

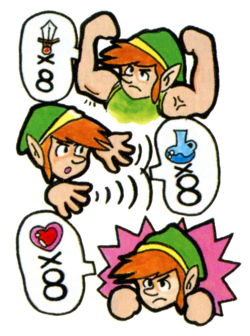

Considering that Zelda games are already based around making Link stronger, the danger is that an RPG system would be redundant. Series precedent, however, points toward a different possibility. Zelda II experimented with incorporating RPG elements, and its results were arguably somewhat successful. It’s hard to gauge just how much it was a subversion of the series’ basic elements. Like the original, it offered exploration, nonlinear gameplay, item acquisition as a prominent gameplay mechanic and for unlocking parts of the overworld, and fast-paced, challenging combat. The RPG elements came from the rudimentary stat-boosting that let the player choose where to invest the levels he had gained.

The trick is that success in Zelda II is hard-won. Imagine the game if you didn’t gain experience from fights! Would braving Death Mountain even feel worthwhile without the significant experience point gain from harder enemies? Likewise, would dying have the same implications if incompetence didn’t carry with it the threat of losing hard-earned experience points? The system took a quirky change and magnified it. Fortunately, its rewards system was also good; by letting the player invest gained levels in different attributes, it extended control to him, a theme that kept with series precedent. Attack, Defense, and Magic were all important to surviving and interacting with the world, and every aspect of that world encouraged enhancement of one of those attributes.

Zelda II isn’t perfect and it’s far from a personal favorite, but it does show how a leveling system need not be a wholesale betrayal of classic series concepts. It’s worth noting that Heart Containers still existed and weren’t rendered redundant in this game; rather, adding Defense simply decreased the amount of damage you took from enemies.

Okami, an action-adventure that is cut from the same cloth as Zelda, has a similar system. Throughout the game, you get varying amounts of praise for interacting with the world, defeating enemies, and doing other tasks. As with Zelda II, different attributes — this time Health, Ink Pots, an Astral Pouch that revives you, and a Wallet — can be invested in. Unfortunately, the Astral Pouch isn’t particularly useful, but there are always good reasons for upgrading your Wallet, Health, and Ink Pots. Ink Pots act as magic in Okami, and they are used constantly. The entire world is built around the magic mechanics, as most Zelda game worlds are built around their signature gimmicks. Health is self-explanatory, and having a steady stream of Health might carry more utility for a certain type of player. Money is everywhere in the game, and you will want to upgrade your Wallet to get the most out of it. As an “RPG element,” this isn’t actually that much of a step up from what’s already in adventure games. It’s easily implemented, easily understood, and gives stat boosts without blatant numbers games.

Okami, an action-adventure that is cut from the same cloth as Zelda, has a similar system. Throughout the game, you get varying amounts of praise for interacting with the world, defeating enemies, and doing other tasks. As with Zelda II, different attributes — this time Health, Ink Pots, an Astral Pouch that revives you, and a Wallet — can be invested in. Unfortunately, the Astral Pouch isn’t particularly useful, but there are always good reasons for upgrading your Wallet, Health, and Ink Pots. Ink Pots act as magic in Okami, and they are used constantly. The entire world is built around the magic mechanics, as most Zelda game worlds are built around their signature gimmicks. Health is self-explanatory, and having a steady stream of Health might carry more utility for a certain type of player. Money is everywhere in the game, and you will want to upgrade your Wallet to get the most out of it. As an “RPG element,” this isn’t actually that much of a step up from what’s already in adventure games. It’s easily implemented, easily understood, and gives stat boosts without blatant numbers games.

Again, these are RPG elements at the most basic level. A modern RPG might point towards a more-specific system that could work for a Zelda game.

Remember Skyrim’s perk system? It’s one of the funnest things about that game, and it’s also not too dissimilar from the tangible rewards you get throughout Zelda games. These do modify your stats, and they let you know they do — but they do it in an accessible, fun way that’s suitable for an action game. Xenoblade takes many of the best elements from real-time RPGs, MMOs, and classic RPG systems and combines them. From the start of the game, you can select different skill trees, which act as perks for your characters. Perks can improve the way your characters fight, give them access to more items at the end of battle, affect combos, and do a myriad of other things.

Item upgrades in Skyward Sword actually emulated “perks” pretty well — there was an immediate, tangible benefit for upgrading the Beetle, for example, that made all the trouble you had to go through worthwhile. In fact, Zelda games are based on immediate rewards; cutting damage in half, increasing your number of Heart Containers, and getting a new item or tunic all change the way you interact with the world. They open new areas or simply let you have fun in the virtual playground Nintendo constructed.

Item upgrades in Skyward Sword actually emulated “perks” pretty well — there was an immediate, tangible benefit for upgrading the Beetle, for example, that made all the trouble you had to go through worthwhile. In fact, Zelda games are based on immediate rewards; cutting damage in half, increasing your number of Heart Containers, and getting a new item or tunic all change the way you interact with the world. They open new areas or simply let you have fun in the virtual playground Nintendo constructed.

More complex, traditional RPG systems that bring numbers and more specific stats to the fore could also work, but they would run the risk of swallowing the adventure elements.

The systems introduced thus far are just some of a myriad of options available, and there’s always the possibility that the developers of a new Zelda game will stumble on a brand new way to incorporate either complex or simplified RPG systems.

I do not think turning Zelda into a pure RPG is a good idea; the games have always been action-adventures. However, since that line is being blurred, RPG elements can be incorporated without undermining the adventure elements. So long as that is the case, there is no reason why this can’t be one of many approaches for a new Zelda game. After all, Aonuma has already expressed an interest in increasing player freedom; what better way to go about it? RPG systems in Zelda wouldn’t necessarily stick closely to precedent, but they would give the games something new to offer without betraying the vision of what a Zelda game can and should be about.