Genre Conventions in Zelda

Posted on February 01 2013 by Legacy Staff

Genre is a peculiar thing. While most works have a clearly identifiable genre, people often disagree about precisely what that genre is; a film may be classified as action, adventure, superhero, thriller, or even film noir depending on who you ask. But despite this variation in perceived genre, none of these responses are wrong, because – like most things – genre can’t be objectively defined.

Genre is a peculiar thing. While most works have a clearly identifiable genre, people often disagree about precisely what that genre is; a film may be classified as action, adventure, superhero, thriller, or even film noir depending on who you ask. But despite this variation in perceived genre, none of these responses are wrong, because – like most things – genre can’t be objectively defined.

At base, genre refers to a category that a work of art can be placed into based on similar traits. The problem with defining genres is that too often, the traits by which a genre is defined are superficial, when a genre should be defined by the experience we desire from it. For example, film noir is often identified by its unique style of cinematography that emphasizes light and shadow as a way of revealing character motives. Thus, that style of cinematography is strongly associated with the genre, but it is not the reason that people flock to it. People enjoy film noir because they want to be told a story of political intrigue, of betrayal and the seedy underbelly of modern life.

In gaming specifically, the problem of genre is further complicated by the aspect of gameplay mechanics. Interaction with a work of art fundamentally alters the experience and the way we have that experience, and thus complicates the definition of gaming genres. Do we determine the genre by the mechanics of the game, or by its aesthetics, such as story, music, and art direction? The tendency of gamers is to take the former option. When defining an RPG, for instance, people often point to leveling systems, stats, adventuring parties and party members, inventory and upgrade systems, and stories told through quests and missions. These are all aspects of gameplay, and again don’t drill down to the core of why people play RPGs.

I am regrettably, woefully under-qualified to address a question as broad as “why we play RPGs”, and will not try to do so. Instead, my focus here is on the aesthetic genre of games, genre that we can derive from the story, music and art of a game rather than its gameplay. The division between the two is fairly distinct; RPGs, to stick with the example, come in many forms, from the standard fantasy RPG such as The Elder Scrolls series to the science fiction RPG such as Fallout. Both series would be called RPGs, but their aesthetic genre is vastly different. There is a much greater discussion to be had about the genre of mechanics in video gaming, but today I am concerned chiefly with the genre of aesthetics.

So, without further ado, let’s talk about The Legend of Zelda, shall we?

One of the great strengths of the Zelda series that I have lauded in the past is its versatility. It manages to present similar yet unique experiences with each new title, both in terms of mechanics and aesthetics. This makes the series an interesting one to discuss with respect to genre aesthetics. While each game in the series fits rather neatly into the large umbrella of genres that covers “fantasy”, there is a wide representation of the various types of fantasy. In particular, there are three types I want to discuss, as they are three types that are most represented in the series: high fantasy, gothic fantasy, and apocalyptic fantasy.

High Fantasy

This is the type of fantasy that most people are familiar with, and in most cases is simply referred to as “fantasy”, or “epic fantasy”. High fantasy features a heavily romanticized fictional world, typically devoid of most modern technology, in which personified forces of good and evil use magic and blades (or, as the classic adage goes, sword and sorcery) to fight an endless struggle. There is almost always a main character or adventuring party that sets off on an epic adventure to seek an object of great power in order to destroy the enemy once and for all. It’s an exceedingly common setup, and can be seen in popular works such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

This is the type of fantasy that most people are familiar with, and in most cases is simply referred to as “fantasy”, or “epic fantasy”. High fantasy features a heavily romanticized fictional world, typically devoid of most modern technology, in which personified forces of good and evil use magic and blades (or, as the classic adage goes, sword and sorcery) to fight an endless struggle. There is almost always a main character or adventuring party that sets off on an epic adventure to seek an object of great power in order to destroy the enemy once and for all. It’s an exceedingly common setup, and can be seen in popular works such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

But as we’ve discussed, genre shouldn’t be defined by its outward appearance, but rather by the desires of the audience. What do people seek to get out of the experience of works of high fantasy? There’s certainly an element of escapism: Most works of high fantasy begin in an idyllic calm, such as the peaceful Shire of Middle-earth, which serves as the closest approximation of “reality” within the work, and then veer outward into the world, with the protagonist(s) experiencing new sights along with the audience, conveying a sense of wonder and awe. The emphasis on the sights of the natural world over technology is a romantic ideal that fantasy pushes more than most genres. But most importantly, I think from high fantasy people desire above all a feeling of adventure with grand stakes. Sure, seeing elves and the sights of Moria and Rohan and Rivendell is an awe-inspiring thing, but ultimately, people latched onto Lord of the Rings and have loved the books and the films for the adventure at the core of the story: the journey of the Fellowship to the fires of Mount Doom.

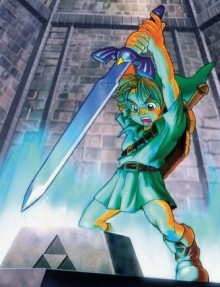

Being perhaps the most common form of fantasy, high fantasy is undoubtedly the most strongly represented style of fantasy within the Zelda series. Several of the larger titles in the series adhere closely to this genre, particularly Ocarina of Time, Twilight Princess, and Skyward Sword.

Ocarina of Time is perhaps the clearest example of high fantasy in the series. Hyrule at this stage in its development is completely devoid of any anachronistic elements of modern technology, and features almost entirely the standard fantasy tropes in terms of art direction. As the series’ first 3D outing, this is to be expected. But despite that, the game does a respectable job fulfilling the core desires that underlie the high fantasy genre. As we’ve discussed in past articles, the game emulates Joseph Campbell’s perennial Hero’s Journey. The game begins in Kokiri Forest, a very idyllic and peaceful environment not too different from Tolkien’s Shire. As the game progresses, settings become increasingly industrial, culminating in the twisted hunk of metal and stone that is Ganon’s Tower. It’s elegant and economical in its invocation of high fantasy.

Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword are a bit less conventional, but still fit the genre fairly well. Twilight Princess is very similar to Ocarina of Time’s world, and ascribes equally well to the Hero’s Journey. While parts of Twilight Princess are decidedly more industrial early on, such as the Goron Mines and the metalwork around Death Mountain, they are accompanied with increased hostility from the Gorons at first, preserving the sense of anti-industrialism and romanticism of a pleasant idyll (Ordon Village) that is typical in high fantasy. Skyward Sword less closely follows the Hero’s Journey, but manages to resemble it on a large scale, and still well captures the sense of adventure with its strong narrative involving the rescue of Zelda. The only sense of industrialism comes from Lanayru Province and the Timeshift Stones that reveal an intricate technological region; this is made up for by the frequent returns to Skyloft, the pleasant idyll that serves as an analogue for reality, as it creates a stronger distinction between reality and the world below, preserving the sense of escapism that helps define the genre.

Gothic Fantasy

Despite what modern culture has come to perceive as “gothic”, gothic fantasy is not inherently defined by dark art design and pessimistic, fatalist worldviews. Instead, gothic fantasy is concerned with more grotesque and bizarre art design, or, to use a somewhat unnecessarily fancy word, “abject” design. Rather than a grand adventure, gothic fantasy tends to be somewhat more focused on horror or calamity befalling the protagonist, and their efforts to overcome it. Gothic fantasy is much less common, but the best representation of it in modern pop culture is in the work of Tim Burton, whose unique visual style falls neatly in line with typical gothic fantasy conventions.

Despite what modern culture has come to perceive as “gothic”, gothic fantasy is not inherently defined by dark art design and pessimistic, fatalist worldviews. Instead, gothic fantasy is concerned with more grotesque and bizarre art design, or, to use a somewhat unnecessarily fancy word, “abject” design. Rather than a grand adventure, gothic fantasy tends to be somewhat more focused on horror or calamity befalling the protagonist, and their efforts to overcome it. Gothic fantasy is much less common, but the best representation of it in modern pop culture is in the work of Tim Burton, whose unique visual style falls neatly in line with typical gothic fantasy conventions.

It’s much harder to pin down the desires of the audience in seeking gothic fantasy. Most commonly, gothic fantasy stories tend to place a premium on exploiting or deconstructing societal norms and taboos. For instance, most modern retellings of Alice in Wonderland place Alice at the center of a social conflict prior to her trip down the rabbit hole. In Tim Burton’s 2010 version of the story, Alice is the eldest daughter of a late business tycoon engaged to be wed to a man she doesn’t love. She flees the wedding, to the shock of the attendees, and falls down the rabbit hole. When she later emerges from the rabbit hole back in the real world, she returns to the wedding, refuses to marry the man, and instead decides to run her father’s company in his stead. It is frequently remarked how unorthodox such a decision was, and that Alice’s actions were strictly against the social customs of the age. The entire central plot of the film involving Wonderland served to develop Alice’s character and lead her to directly challenge the social customs. This is the core of many gothic fantasy stories: a challenge of societal norms and values.

Gothic fantasy also serves for many as a form of horror. The uncanny is a strong force of terror, one of the dominant forms of fear, and the visual style of gothic fantasy tends to provide a multitude of uncanny sights and sounds. Similarly, gothic fantasy tends to come from established authors of horror. For example, Stephen King, the noted horror author, wrote a gothic fantasy series known as The Dark Tower. Thus a source of terror and a challenge to societal norms tend to be at the core of most works of gothic fantasy.

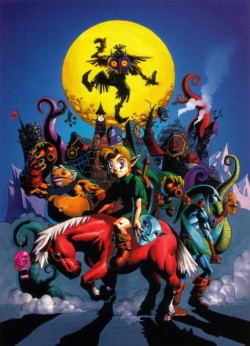

There is only a single significant example of this type in the series, but it’s very intricately crafted and an exceptional example of the genre: Majora’s Mask.

I scarcely need mention the art design of the game; though graphically similar to Ocarina of Time, there’s a tremendous sense of stylization that bends toward the grotesque and horrifying. Simply turn to things such as Kamaro’s Mask and Link’s faceless dancing, the animation that plays when Link puts on a transformation mask, or the most stunning astronomical feature in the game, the slowly falling Moon.

But the game manages to do several things within the confines of the series itself that secure its place as gothic fantasy. It subverts the social norms not of our society, but of Hyrulian society. Terminian society is very, very different, and is different in ironic ways. For instance, the Deku, previously seen as little more than a nuisance when enemies and as shifty businessmen when neutral, are a regal society with a clear hierarchy and racial pride, as evidenced by their strict sense of security at the palace for non-Dekus. Similarly, the Gorons, previously inhabitants of a volcanic region, are seen here in the freezing environs of a snowy mountain range. The human kingdom in the region, the ancient kingdom of Ikana, is no longer standing; whereas in Hyrule, the human/Hylian kingdom was the greatest power in the land, Ikana is a barren wasteland. These twists on the social norms established in Ocarina of Time work to deliver the social disruption common in gothic fantasy.

Similarly, the game has a significant sense of terror through the uncanny. See, as mentioned previously, the transformation masks, and the ways they are acquired: Through healing the sorrows of dead or dying creatures. See the game’s music design, particularly the oddly haunting Song of Healing. See the Moon Children and their probing questions into morality and self-worth, and the strange calm of the moon itself. There’s a lot of “strangeness” in Majora’s Mask that serves to inspire a sense of terror in the player through the uncanny.

Apocalyptic Fantasy

When the word “apocalyptic” is in the name of the genre, you just know you’re in for a good time. This genre is fairly self-explanatory. It focuses primarily on the exploration and rebuilding of society in a world that has “ended”, or faced a catastrophic event that destroyed any prior societies and left a clean slate. There are clear examples of this genre, such as Fallout, Metroid Prime, and (arguably) Dark Souls. Unlike the other types of fantasy we’ve discussed, apocalyptic fantasy doesn’t have a particularly iconic visual style, with each individual example adopting its own interpretation of a post-apocalyptic world.

When the word “apocalyptic” is in the name of the genre, you just know you’re in for a good time. This genre is fairly self-explanatory. It focuses primarily on the exploration and rebuilding of society in a world that has “ended”, or faced a catastrophic event that destroyed any prior societies and left a clean slate. There are clear examples of this genre, such as Fallout, Metroid Prime, and (arguably) Dark Souls. Unlike the other types of fantasy we’ve discussed, apocalyptic fantasy doesn’t have a particularly iconic visual style, with each individual example adopting its own interpretation of a post-apocalyptic world.

The focus on exploring what remains of the world and the rebuilding of society points to a few clear motivations for seeking out this genre. There is likely a bit of desire for assurance that, in the wake of such catastrophe, society will rebuild itself over time. Apocalyptic worlds play to the innate desire of humans to explore the world, given that our world has been, for the most part, fully explored. By shattering a familiar world with an apocalyptic event, apocalyptic fantasies provide new things to explore in worlds that have been mostly explored. For example, look to Fallout 3’s Capital Wasteland. Washington D.C. and the surrounding area have definitely been explored in the real world, but Fallout’s apocalyptic future provides a way for us to satisfy our desire to explore by making that world unfamiliar again.

The two best examples of this genre in the series are A Link to the Past and The Wind Waker. Now, these may seem like very unconventional examples of this genre, but with a bit of examination, it becomes clear that they fit rather well.

The Wind Waker opens with a story of Hyrule being flooded by the gods in order to stop Ganon, since the Hero of Time had not returned to vanquish him a second time. This is our apocalypse. Many, many years after that flood, life on the surface has rebuilt itself in the form of a Great Sea with humans inhabiting islands. This gives us a brand new world to explore, despite technically being a world we are familiar with. It defies the typical convention of the genre with its fiercely exuberant demeanor; the art direction, sound design, and even the characters’ animations are all wonderfully expressive and whimsical, whereas the typical apocalyptic fiction story will have a great sense of somberness. This speaks to a great deal of hope being conveyed through the typical desires of assurance and exploration, and given that the King of Hyrule wishes for hope for the children at the end of the game when he touches the Triforce, that seems to be the goal of the game on all fronts.

A Link to the Past also gives us both the world before and the world after; there’s the main overworld, Hyrule, and then the post-apocalyptic Dark World created when Ganon laid his hands on the Triforce. As a dark mirror of the standard overworld, it gives us a new area to explore while showing us that evil has caused the collapse of society. It heightens the sense of exploration by comparing the two worlds more directly. While Hyrule’s developed world is suitably compared with the socially dead Dark World, A Link to the Past ultimately fails to deliver on one of the genre conventions of apocalyptic fantasy. The Dark World is not a nascent society in the process of rebuilding, and shows no evidence of having ever been a real society.

Conclusion

Ultimately, this discussion of genres in the Zelda series has been an exercise in breaking down typical genre definitions. Genre shouldn’t be defined by superficial characteristics, but rather by what we, as consumers of art, desire from the genre; the experience we wish to have by participating in a given work of art.

Equally, the Zelda series is not a broad stroke “fantasy” series; no, its genres, while all under the large fantasy umbrella, are in reality diverse and, in terms of the genre of aesthetics, appeal to different core desires.

While there are a host of other genres, this was a much simpler introduction to the wider understanding of genre. I hope it has been an enlightening discussion, and one that will inspire more critical thought when it comes to genre conventions.