Daily Debate: Do You Prefer Linear or Open-Ended Zelda Dungeons?

Posted on September 06 2021 by Mike Midwood

Dungeons have been a central aspect of The Legend of Zelda since the beginning and are my favorite part of any Zelda adventure. They’ve been presented as caves, temples, trees, giant fish, and pirate ships. Most recently, Breath of the Wild’s Divine Beasts have been the source of dungeon-esque content, in the form of enormous, animal-shaped laser weapons. While their appearance and context has changed dramatically, they’ve continued to provide the same utility to the series; a more intense, focused segment of gameplay separate from the larger overworld. How that challenge is structured, in terms of puzzles, navigation, and presentation, has shifted over time into distinct groups and periods. While there are exceptions, Zelda dungeons have generally changed from labyrinthian complexity toward a more streamlined puzzler experience. Both approaches have their merits, but which do you prefer?

Prior to Zelda‘s leap into the third dimension, there were harsh limits on how much information could be presented to a player. As such, it was extremely difficult to give dungeons any kind of thematic flare, and puzzles had to remain conceptually simple. Pushing a block, stepping on a switch, or clearing a room of enemies was the answer to the vast majority of roadblocks. The challenge of these dungeons typically came from navigating a complex web of items, keys, and locked doors. A great example is Misery Mire from A Link to the Past. Misery Mire has a high proportion of optional rooms, leading to the inclusion of five keys, though only two are actually required for completion. All of the keys in Link’s Awakening‘s aptly named Key Cavern are required, but they can be retrieved in any order. The potential permutations of progression lend a real sense of exploration to these dungeons, and no two playthroughs are likely to be the same. In the era of these classics, that navigational complexity had to be sufficiently interesting, because both of these examples are devoid of thematic context. They’re both nondescript collections of perfectly square rooms with no set dressing. This limitation, while understandable, is a blight on dungeons from Oracle of Seasons and Oracle of Ages, where complexity is the highest and uniqueness the lowest. Sword and Shield Maze and Ancient Tomb are long, laborious drudges through dull, identical rooms.

The dungeons of more recent Zelda titles have seen an almost complete inversion of priorities. The Wind Waker is where this shift begins in earnest. Most (not all) dungeons from this point forward have a single, prescribed method of completion. They have significantly fewer rooms and they’re almost all required. Focus is shifted to large-scale, high-concept puzzle motifs, like the Earth Temple’s mirrors or the Wind Temple’s giant fan. Much more effort is placed on presenting the dungeons as unique, contextualized architectures with history and purpose in the world. Twilight Princess succeeds tremendously in this capacity, filling each of its many dungeons with memorable moments and impressive areas. Even mundane locations like the Goron Mines have a sense of place in the world and the streamlined progression allows each of the developer’s interesting inclusions to be seen. The Temple of Time from Twilight Princess is the most linear dungeon in the entire series; essentially a hallway the player walks to the end of before returning to the entrance. Despite this, it’s a fun succession of puzzles, enemy encounters, and memorable iconography. It makes sense that, as games became more difficult and costly to produce, developers want to make sure their creations are seen by every player. Imagine if seeing the giant Buddha in Skyward Sword‘s Ancient Cistern was optional. It’s just a shame that this often limits the complexity and variety of dungeon designs.

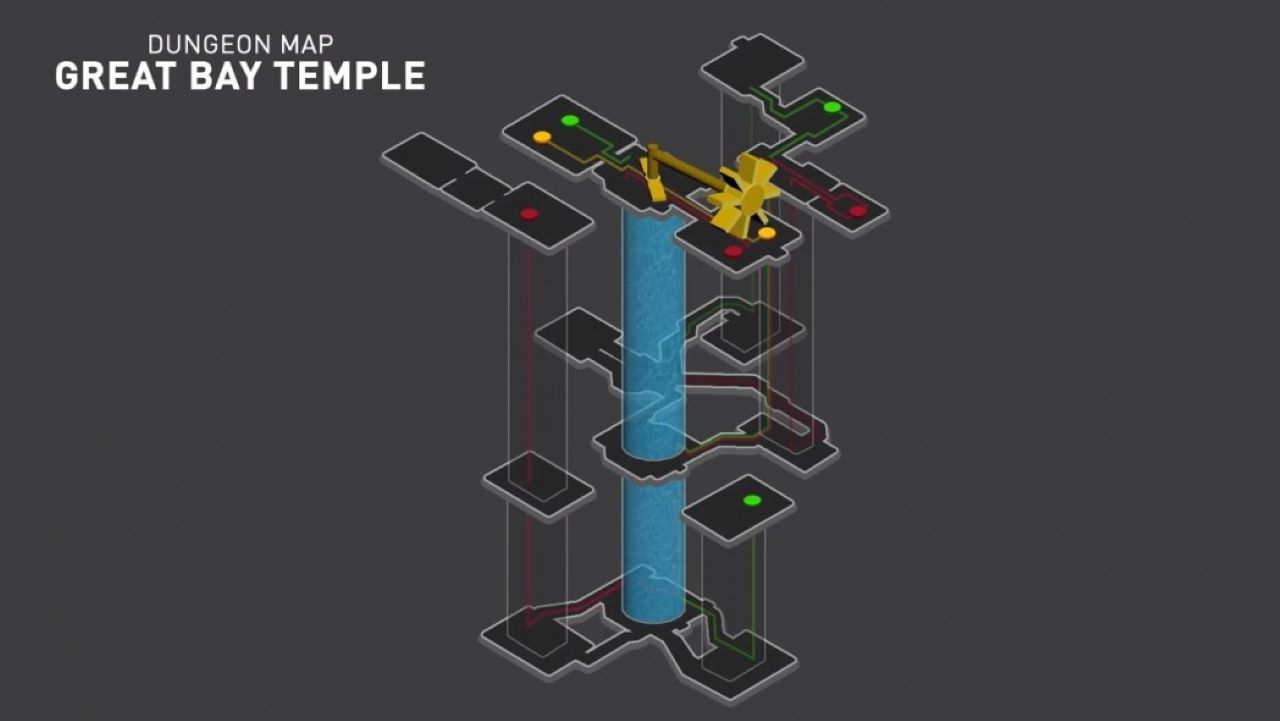

Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask have gone conspicuously unmentioned, and as they’re my favorite games in the series, it’s no surprise I think they manage to find a perfect balance between these two styles. The former marks the beginning of the 3D era and the beginning of complete visual distinction between dungeons. Obviously, they aren’t as detailed as the dungeons of future games, but the elemental touches are enough to make each feel unique, and the beginnings of historical hinting can be seen in the Forest Temple, Shadow Temple, and Spirit Temple. While completing these dungeons is a broadly linear succession of events, there’s often some openness to accomplishing those events. In the Forest Temple, the main objective is to hunt down the Poe Sisters. Reaching the first one will always require three keys, but those keys can be collected in any order. The sense of exploration is maintained, despite the whole of the dungeon being fairly guided. Collectibles like Gold Skulltulas are often placed in entirely optional rooms rather than along the critical path. The dungeons of Majora’s Mask continue to build on these concepts. Many lament that there are only four, but I consider this to be the best set in the series. With the exception of Woodfall Temple, each dungeon has incredible theming and context. They’re all designed around understanding and manipulating a central mechanic, allowing for diverse routes of progression and memorable moments. Each dungeon is compact and streamlined enough that getting stuck rarely means a lengthy trek across the map. They all have entirely optional areas to find stray fairies in. I’ll admit I’m biased toward these games, but I think the Zelda series’ dungeon design peaked on the N64.

Some games aren’t included here and there are obviously exceptions, but what are your thoughts? Are newer dungeons too simplistic? Are older dungeons too confusing? Which type of dungeon do you prefer? Let us know in the comments below!

Featured Image: Game Maker’s Toolkit

Hi, I’m Mike Midwood and I’m a Senior Editor at ZeldaDungeon! Video games and literature are my greatest joys in life. An avid Zelda fan, some of my other favorite games include the Resident Evil and Dark Souls series. I hope you enjoy my content here on ZeldaDungeon!

“The sword has no strength unless the hand that holds it has courage.”