Broken Worlds: The Melancholy Settings of The Legend of Zelda

Posted on May 27 2011 by Legacy Staff

One of the most-asked questions among Legend of Zelda fans is “Why do these games feel so different from other games,” or, alternately, “Why do these games feel so different from most other Nintendo titles?”

One of the most-asked questions among Legend of Zelda fans is “Why do these games feel so different from other games,” or, alternately, “Why do these games feel so different from most other Nintendo titles?”

While the answer rests in a mix of elements, I think the reason why they have a differing feel from many of the more “happy-go-lucky” Nintendo titles rests in the settings given to the Legend of Zelda games. While say, Pokemon, gives us a “feel of adventure” similar to the experience of Zelda, it has an overall new and modern feel to it – with the technology related to the keeping of Pokemon, the rather whimsical premise of capturing and befriending many strange creatures, and the presentation of a safe world a young kid can wander as an amateur naturalist of sorts. There are other notable examples. Every Super Mario Bros. game I’ve played presents the audience with a surreal dream-world of sentient mushrooms and turtle-dragons that’s just too strange to take too seriously. Donkey Kong Country is fun with monkeys. Metroid is far from happy-go-lucky, but even it has a different feel than Zelda, mainly due to its science fiction universe of high technology. The various legends of Zelda take place in worlds of ancient myths and magic.

The most “Zelda-like” non-Zelda game I’ve played in recent memory is the Playstation 2 title Shadow of the Colossus. Although different from Zelda in a number of ways (perhaps most notably, you can stand in one spot for a while without multitudes of things trying to kill you), it had one thing that reminded me, strikingly, of every Legend of Zelda title I’ve played – a sad sense of wandering a broken world. The Forbidden Lands were a vast landscape dotted with the ruins of ancient temples and works, much like Hyrule. While Shadow of the Colossus is tragic in multiple ways (as anyone who’s completed it knows), the setting is what struck me immediately as truly melancholy and gave me the same twinge of emotion I’ve always found with Zelda.

While the Legend of Zelda games are filled with whimsy and wonder, Hyrule and surrounding worlds and territories have all been broken worlds.

Examples of how these games are set in worlds built upon ruins and melancholy are below – every Zelda title I have personally played:

Hyrule Through the Ages

The idea for this article was prompted by an AIM conversation I had with an online friend of mine. While he did not think highly of the Zelda series, he had played the first three titles and generally enjoyed them. When talking about how we had both grown up playing the original Legend of Zelda, he spoke of how he’d always thought of it as a dark game because it “felt like a broken world.” He prompted me to think about it: it presented us with the tale of Hyrule’s takeover by a dark being described in the manual as an entity that no one had seen and lived, with a world full of people reduced in their fear to hiding in caves and in secret places beneath trees. There are no towns in this game, nor even hints thereof – the only thing that hints that a significant population once lived in Hyrule are the labyrinths themselves, infested with monsters. The original Hyrule was a lonely, dangerous wilderness, not a kingdom so much as a wasteland tormented under the rule of evil, an empty world full of fear. Of course, it is dangerous to go alone…

Zelda II takes things a step further. For those unfamiliar with this game, the manual speaks of an ancient Princess Zelda (presumably different from the Zelda rescued in the last game), a curse of sleep, a prince’s grief (leading him to declare that all girls born into the royal house would carry the name of his cursed sister), a new mission for Link, and, of course, the pursuit of his heroic blood. According to the game’s story, the minions of the defeated Ganon are seeking to make an unholy sacrifice out of Link in order to bring their dark lord back. This is definitely a sad back story, struck-through with a strong thread of horror.

While set in a different part of Hyrule than the first (there are thriving towns), Link wanders through ancient palaces and the occasional devastated town (Kasuto) while fighting off creatures that are, in the most literal sense, after his blood. While the population centers are numerous, the towns are set far apart from each other, with large swaths of monster-filled country in between, giving one the feel of a severely disjointed kingdom. The setting doesn’t feel much more developed, new, or any safer than the setting of the first game. Hyrule is still an ancient land that has been ravaged and has lost its glory.

While set in a different part of Hyrule than the first (there are thriving towns), Link wanders through ancient palaces and the occasional devastated town (Kasuto) while fighting off creatures that are, in the most literal sense, after his blood. While the population centers are numerous, the towns are set far apart from each other, with large swaths of monster-filled country in between, giving one the feel of a severely disjointed kingdom. The setting doesn’t feel much more developed, new, or any safer than the setting of the first game. Hyrule is still an ancient land that has been ravaged and has lost its glory.

A Link to the Past is a game not only with ancient dungeons, but an entire mirror-universe. The Dark World is literally a twisted version of Hyrule. It is full of ruined landscapes and people whose personality flaws and personal sins have turned them into all manner of dark and suffering creatures. The Dark World, ruled by Ganon, is a broken world, indeed. One might even say that it is the only time in Zelda where Link has visited a version of Hell itself. It becomes one’s mission, as Link, to keep Ganon from taking over the Light World and making it into as twisted a place. Link gets to see the transformation of various people first-hand, from the bully turned into a beast, kicking around an innocent kid cursed to become a ball for his indecisive nature, to the sad Flute Boy, who became trapped there and only wishes to hear one last song on his flute before the curse takes him over completely, freezing him into the form of a tree. The Dark World contains whimsy in the strangeness of its monsters and in Link’s transformation into a cartoonish pink rabbit, but it remains a devastated place, a cruel world that its inhabitants long to escape.

The first of the 3-D style Zelda games was also, perhaps, the one that truly solidified a Hyrule built upon ruins. The temples all have a very ancient feel to them, even the ones that are implied to still possibly be in active use by their peoples. The Forest Temple, in particular, gives one the feel of an old mansion haunted by ghosts. The Shadow Temple looks like an ancient torture-chamber, prison, and execution-center. The ultimate broken world feel occurs when Link wakes up from his seven years of slumber to find Castle Town destroyed, ReDeads milling about, Ganon’s Tower replacing Hyrule Castle and a kingdom full of suffering people. Perhaps the most sorrowful thing about this world is that Link learns that he helped to create it. He and Zelda, in their attempts to stop the tyrant’s takeover, facilitated it by opening the way to the Triforce. The adult world of Ocarina of Time is not only a broken world, it is a broken world created by the protagonists’ mistake, and now he must fix it.

Majora’s Mask is unique because it presents Link with a world that’s on the cusp of being laid waste and it’s your job to stop it. On a forum thread regarding how people might describe this game, my answer was simple: “A whimsical nightmare.” Majora’s Mask is often cited as the darkest and the creepiest of the Zelda games, which is not hard to do with a plot centered upon impending doom and a time-limit. All of the colorful and whimsical elements to the setting only serve to underscore and heighten the horror. Termina is a world that’s about to be broken, and broken completely. In addition to this, there is Ikana Canyon, a country of the dead filled with ruins, graves and ghosts. The only inhabitants are the undead, between the ghosts of the Garo and the skeletal remnants of the Ikana Royal Family and their Stalchildren soldiers. This brings up a lot of wondering about that land (such as the Stalchildren – were they child soldiers)? In addition to a plot that has Link dealing with spirits and impersonating dead people, Termina – a world in ruins that’s about to be destroyed – makes for a melancholy setting.

There is not much to say about the Oracle games other than the standard ruins that crop up in all Zelda games apply. The dungeons are generally hidden in ancient ruins, old graves, temples and the like. Oracle of Seasons involves a plot of broken nature while Oracle of Ages involves trips centuries into the past, presumably before some things became ruined, but still an age built upon ruins in its own right and the additional possibility of people being erased from existence if things go wrong.

How can something so cartoon-like and candy-colored as The Wind Waker have a sense of melancholy and brokenness? Two words: Flooded Hyrule. The setting of the game, as seen in the opening credits, is of a world that was built over a land that was drowned. Add to this the old ruined temples and the ghosts of murdered Sages and this bright, happy toon-world doesn’t seem so happy-go-lucky anymore, does it? The characters of the islands all seem to have a certain sad longing for the kingdom of legends that is no more and its long-gone Hero. The opening credits provide the legend of this Hero, most notably, that he rode away from the land and did not return. When evil rose and the people prayed for him, he did not return. This gives the world of The Wind Waker a deep sense of abandonment.

The abandoned world comes to the fore when you are treated to a visit to the dormant Hyrule Castle on your mission to fetch the Master Sword. You look around the ruined main hall of the castle, to the old paintings and the tattered banners – then up, up and up at the statue of the Hero you are expected to live up to. Then you know that something has been lost that cannot truly be brought back again. Cue the tears from the Ocarina of Time fans.

I think one of the reasons why I loved Twilight Princess as much as I did was because it is a world that is blatantly full of ruins. They are everywhere – from the old-looking bridges that look like they’ve seen better days to random stonework along trails and passages… It is like the designers took the idea of the temples in Ocarina of Time and upped the volume, putting the remains of things that may have once been parts of cities and palaces absolutely everywhere. Even the graves in the Kakariko Graveyard do not look maintained, with their huge headstones off-kilter. As a bonus to all this, when one goes to the Sacred Grove, the remains of Ocarina of Time’s Temple of Time are there and one can literally visit it in the past, outside-of-time by using the Master Sword as a key. The Grove also serves the function of showing an old temple from an earlier game succumbing to nature and there are many little connections like that to Ocarina of Time. It truly gives one a sense of “one era is dead and is passing into another.”

I think one of the reasons why I loved Twilight Princess as much as I did was because it is a world that is blatantly full of ruins. They are everywhere – from the old-looking bridges that look like they’ve seen better days to random stonework along trails and passages… It is like the designers took the idea of the temples in Ocarina of Time and upped the volume, putting the remains of things that may have once been parts of cities and palaces absolutely everywhere. Even the graves in the Kakariko Graveyard do not look maintained, with their huge headstones off-kilter. As a bonus to all this, when one goes to the Sacred Grove, the remains of Ocarina of Time’s Temple of Time are there and one can literally visit it in the past, outside-of-time by using the Master Sword as a key. The Grove also serves the function of showing an old temple from an earlier game succumbing to nature and there are many little connections like that to Ocarina of Time. It truly gives one a sense of “one era is dead and is passing into another.”

There are also the interesting ruins of the mansion on Snowpeak. Exploring it reveals strange crests everywhere, the possible coat of arms for a prominent family or even, perhaps, a onetime enemy of Hyrule. The place has armories and canon-ranges, which speaks of it having been a fortress for some forgotten war. In addition to this, the Twilight itself paints a swath of sadness over the lands that it touches, twisting the monsters into even stranger forms than they originally had and all of the humans and neutral animals into forlorn spirits, shadows-of-the-shadows, who are, in Princess Zelda’s words, “gripped by a nameless fear.”

Endings and In-Betweens

In addition to the locations for each and every game, there are some melancholy elements to consider in their stories and the overall Legend that paints the settings of the games with a brush of seriousness.

For one thing, the games don’t always have the happiest of endings for Link. While the first three games ended with completion and celebration, many of the games give him a bittersweet ending, at best. This seems to have been a trend since Link’s Awakening (which I did not elaborate upon in above article because I have yet to personally play it). From what I have read of it, its broken world was a dream-bubble broken by Link, himself – an ending that left him adrift. Ocarina of Time ends with Link losing his partner, Navi, the little fairy he had waited his childhood for, your companion and faithful helper (like it or not) through your dangerous journey. It also ends with the Hero being sent back to a past that, while untainted by Ganondorf’s evil, also cannot remember his great deeds. It is arguable that he also “cannot go home again” as his entire perception of the world and who he is has been changed.

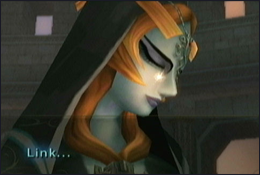

Majora’s Mask has you leaving Tatl behind, and, it is implied, the entire world of Termina, full of its characters and their stories. The Wind Waker has you saying goodbye to the ancient King of Hyrule, filled with his regrets, as he drowns along with the old kingdom. This is a game where you know that your partner actually dies in the end. Twilight Princess involves the shattering of the gateway between the world that is Link’s home and another world, with the parting of another valuable partner – one that’s easy to grow attached to because she’s given perhaps the strongest personality of a partner in any Zelda game to date. Some fans consider Midna a friend to Link, while some consider her a possible love-interest – for fans of the latter, this ending is especially sorrowful. At the end, he is seen riding away from Ordon Village, which implies that he, much like the Hero of Ocarina of Time, “cannot go home again.”

Majora’s Mask has you leaving Tatl behind, and, it is implied, the entire world of Termina, full of its characters and their stories. The Wind Waker has you saying goodbye to the ancient King of Hyrule, filled with his regrets, as he drowns along with the old kingdom. This is a game where you know that your partner actually dies in the end. Twilight Princess involves the shattering of the gateway between the world that is Link’s home and another world, with the parting of another valuable partner – one that’s easy to grow attached to because she’s given perhaps the strongest personality of a partner in any Zelda game to date. Some fans consider Midna a friend to Link, while some consider her a possible love-interest – for fans of the latter, this ending is especially sorrowful. At the end, he is seen riding away from Ordon Village, which implies that he, much like the Hero of Ocarina of Time, “cannot go home again.”

What goes on between the series games is another thing to consider. While a Pokemon game might end with your character becoming a Pokemon Master and the next game starts out a completely new adventure with a completely new protagonist, and while Super Mario Bros. and Metroid are all series games starring the same protagonists, The Legend of Zelda is unique in that it is governed by archetypes. While it is implied that Ganon/Ganondorf is the same recurring villain, Princess Zelda and Link, while sharing the “Princess” and “Hero” archetypes and the official names of all their counterparts in games past, are different. With the exception of direct sequels, there is a new “Link” in any given game, sometimes implied to be the descendant or spiritual-successor to the last one. To put it bluntly, the Legend of Zelda games give us new eras, different ages spread far apart from one another and, in doing that, it is implied that somewhere along the line, the Heroes you’ve played and the Princesses you’ve saved in some games have died. When you play a distant sequel game to one you’ve played, you know that the Hero you played the last time is dead and gone. When you play a game that is a prequel to one you’ve played, you know that you’re playing a protagonist who, storywise, is dead in the history of the last game you’ve played. Even if you hold to the fan-theory that Link is a perpetual reincarnate, he’s still never entirely the same Link. This sense of a history, an ages-long legend, definitely gives these games a sad feel.

Hyrule and the various other lands in The Legend of Zelda have never been shining and new, and despite whimsical elements, never purely lighthearted lands. The settings for the games have always shown lands built over ruins and lands with a sense of danger and sadness – broken worlds with a tone of seriousness appropriate to epic myth and high fantasy. This, perhaps, is what accounts for the bulk of their more serious and all-around “different” feel from most of Nintendo’s other big titles.

Shadsie writes and posts original fiction at her blog, Sparrowmilk http://sparrowmilk.blogspot.com/ she posts fan fiction on Fanfiction.net http://www.fanfiction.net/u/6569/Shadsie and artwork on Deviant Art http://shadsie.deviantart.com/